IChemE members join group advising government on net zero plans

ICHEME members are working with representatives of the wider engineering discipline to advise the UK Government on how it can achieve its net zero emissions target, with a strong emphasis on the need to adopt a systems approach.

Mark Apsey, Chair of IChemE’s Energy Centre, has joined a working group formed by the Royal Academy of Engineering’s National Engineering Policy Centre. He will represent IChemE as one of 14 experts that seek to unite the engineering profession around a shared vision for decarbonising the UK. The Vice-Chair of the group is Nilay Shah, Head of the Department of Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London.

Over the next 18 months, the group will identify actions this parliament can take to lay the foundations for achieving its net zero target by 2050. It will gather evidence, provide a forum for debate, publish briefing papers, and seek to stimulate debate across society.

“The UK has less than 1,600 weeks to meet the target of net zero territorial emissions; it is a massive undertaking,” the group writes in its opening report. “It will involve simultaneous transformation of several vital, interconnected infrastructure systems: from transport and housing, to energy and manufacturing. It requires developing whole new industries to maturity and supporting sweeping societal, cultural, behavioural and structural change. A strong government-led vision for 2050 is needed now to drive coordinated, achievable action across all parts of society and government, with urgency and ambition.”

Systems thinking

The group warns that unless the UK plays a strong international leadership role it will risk leaving future generations impoverished and the UK less commercially competitive. It notes that government must take difficult decisions with incomplete information concerning huge challenges including replacing or retrofitting all major emissions sources. And it must connect its approach to areas of policy that are currently treated in isolation, noting as well as infrastructure and technology adoption the net zero target will impact finance and regulation, and require changes in personal behaviour and social norms.

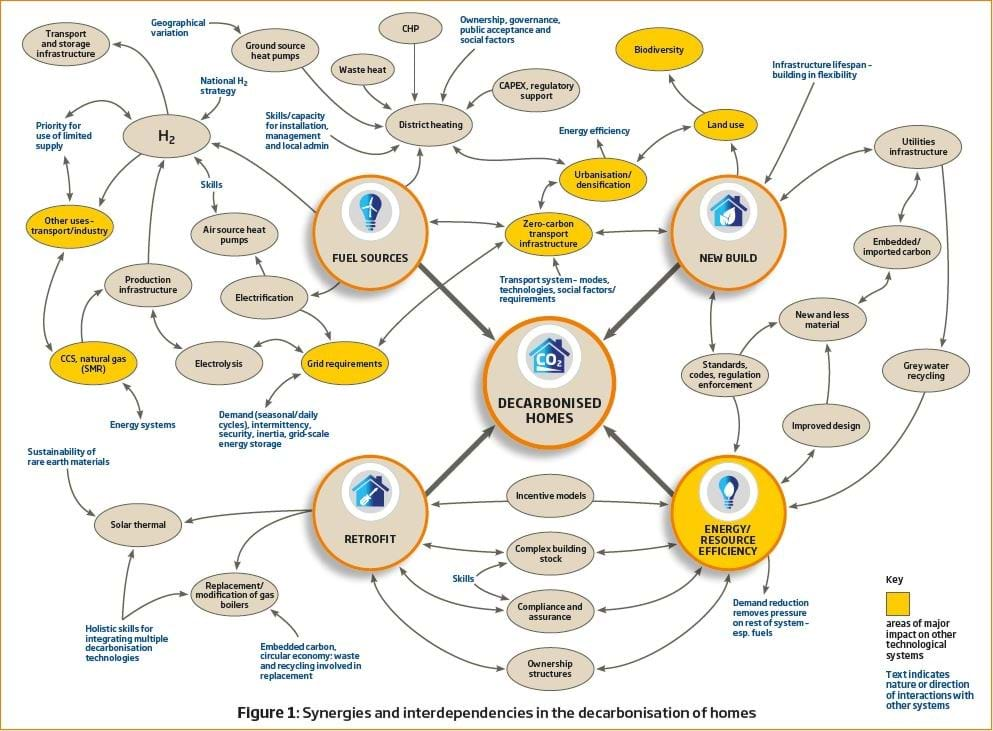

“Without an over-arching system architecture or system transition strategy in place, there is a risk of failing to adequately account for the knock-on effects that changes in one sector will have on each other. For example, transport decarbonisation strategies will make assumptions about, and have ramifications for, requirements for houses, workplaces, energy infrastructure and vice versa,” the group explains.

Its report includes a graphic of a systems views of the web of interdependencies that will impact the decarbonisation of homes (see graphic). Homes accounted for 18% of UK emissions in 2018, primarily through burning natural gas for cooking and heating. There are a series of government-funded projects underway looking to support switching natural gas for hydrogen including H21 and HyNet. The report points out that just on this point alone, a rollout of hydrogen has implications on the supply of natural gas and CCS to produce green hydrogen, and gas grids for transport will need to be redeveloped, boilers retrofitted, and safety cases developed.

Priority topics

The working group has identified a series of priority topics to advise government on including how to recover from Covid-19 with net zero in mind; decarbonising construction; skills and training implications; and addressing climate change through decentralised systems planning.

The National Engineering Policy Centre draws together 39 UK engineering institutions and organisations, including IChemE, representing 450,000 engineers. The working group said it recognises there are a range of views on how to achieve net zero, and committed to gather robust evidence and make it clear when there are gaps in knowledge or where there are multiple options available.

Sir Jim McDonald, President of the Royal Academy of Engineering said: “As engineers we can capitalise on our experience and use of systems approaches in bringing together different elements – from technological to financial, from regulatory to ethical – to create practical solutions and help the government to make tough and lasting decisions that will reduce harmful emissions whilst creating jobs and benefitting people’s lives.”

Apsey said: “Chemical engineers work across industries where there is a great responsibility to tackle many of the world’s grand challenges, including the need to protect the earth from the threats of climate change. Working alongside other professional engineering institutions in the National Engineering Policy Centre, I believe we all have a critical role to play in developing sustainable systems and processes which enable us to thrive and achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.”

Last year, Apsey led a group of IChemE volunteers that created an Energy and Resource Efficiency Good Practice Guide that was published by the IChemE Energy Centre and outlines how engineers and organisations can reduce energy and waste in order to tackle climate change.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.