Why we Need to Engage with Primary School Children – and How to do it Effectively

Joy Parvin has 32 years of working in primary schools’ outreach under her belt. She reflects on why it is so important for chemical engineers to engage with the youngest in our society, and shares tips from three Children Challenging Industry ambassadors who are out there doing it

I TRAINED as both a chemical engineer and a teacher. This combination puts me in a unique position to consider what is impactful from both perspectives, and I have been lucky enough to be able to constantly build and innovate in this area, as the director of the Centre for Industry Education Collaboration (CIEC) since 2008.

I still recall how tricky I found it to explain to anyone what a chemical engineer “does” and was constantly refining my references to “cooking on a very large scale” and other turns of phrase. Even after teaching for a few years, I could not easily see how the work of chemical engineers in the chemical industry and beyond, could be made relevant to ten-year old children.

Then I came across CIEC, began piloting their activities in my after-school science club, and soon started writing these activities for the Centre to publish. I was introduced to the practice of visiting industry, to listen to STEM professionals and visit their working environment, in order to create meaningful stories for classroom science; a practice that continues to be fundamental in ensuring a robust connection between industry and schools. Visiting Jealott’s Hill research centre to learn about pesticide research and development was when I really began to see the work of scientists and engineers through the eyes of a teacher and with the knowledge of a chemical engineer. I could ask the right questions without fear of looking silly, and quickly transfer the information into simple activities that would support the all-important teaching of the science National Curriculum. Schools are not likely to engage unless that robust connection between your world and theirs exists.

The importance of schoolchildren meeting “real” chemical engineers, and ideally in their working environment, has become clearer and clearer to me over the years. And of equal importance is getting the communication right. We so easily fall into our own language of work – teachers talking about AfL (assessment for learning, for those of you who are not familiar with this), and chemical engineers talking about P&IDs (no need for me to explain those to you).

So, how do we cross this bridge? Well, be brave. Then make a connection with an organisation like CIEC which exists purely to help both teachers and engineers take those first steps to meet in the middle, shake hands, and find that common language. The team of advisory teachers at CIEC will help you consider alternative language – such as replacing chemical with ingredient or product, powder, liquid etc; help you explain chemical engineering in terms of problem-solving and teamwork, and tailor your specific story to be told to an enthralled group of primary children, rather than “switch them off” with difficult language and concepts.

Over the last 28 years, the team at CIEC has trained 1,200 STEM professionals from chemical and allied companies across the UK. These Children Challenging Industry (CCI)1 ambassadors have shared their experiences with 62,000 children, either in their classrooms or on interactive site visits. On pages 49 and 50, three ambassadors, each at different stages of their outreach journey, share their experiences.

One thing you will note from those case studies, is the description of practical activities. Involving the children in “doing something” is so important to the engagement and learning process. A practical approach is a significant component of the CCI programme, starting with the way in which the CIEC team ensures the science curriculum and industry stories are taught through practical work, through to ensuring that engineers plan practical interactions – whether this is in the classroom or during a site visit.

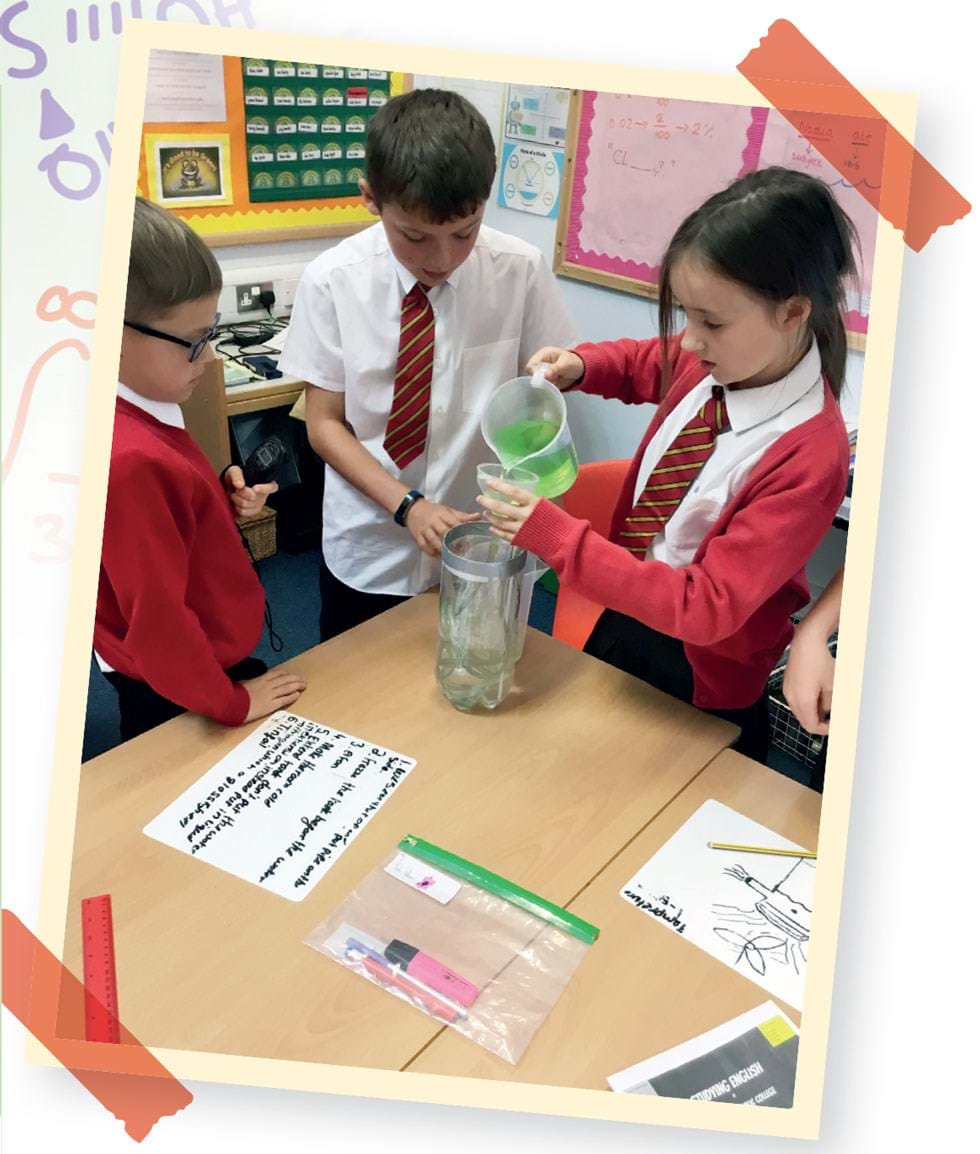

One of the first classroom activities I developed in the early 1990s was a “pop bottle heat exchanger”, which remains popular in primary classrooms today. Another activity challenges children to create a simple sensor, so when their pop bottle is getting full, a buzzer buzzes or a light lights up. A third activity sets children the problem of filtering a pop bottle of “muddy” water as efficiently as possible. Yes – pop bottles are standard primary science equipment!

The intention is not for chemical engineers to lead any of these activities, but to consider what they themselves add to compliment this classroom science. For example, share photos and videos of real heat exchangers and jacketed vessels, allow children to handle real sensors or components removed from pilot plants or labs once they are no longer in use, or use large filters or filter socks for filtering bucketfuls of muddy water.

Having worked with many companies across the UK, I know there is a level of commitment required to working with primary-aged children beyond the day-to-day business of the company. I also know that it takes people with long-term vision to appreciate that these efforts may take many years to have an impact on our future workforce. I have met a number of STEM professionals in industry over the years who have told me they were first inspired to choose their career path when visiting their local company as part of the CCI programme.

Of course, there is an immediate impact, on the children, teachers, and our colleagues in industry, best summed up by one of the children on the bus home from a site tour: “This was the best school visit ever!”

Why primary-aged children?

Our research2 has consistently shown that children “switch off” from science-related careers by the age of 11; a finding echoed by other researchers in the field.3 Children have decided what they don’t want to do, and as soon as they get an opportunity to drop science subjects, they will. Even though the vast majority (around 85%) enjoy science, a similar 85% have decided it is not for “people like me”. Children need to meet people that look like them and sound like them to consider it a possible future career for themselves.

Why does industry get involved?

- Focus on the community/children

- Corporate social responsibility

- Staff-related reasons: team building and staff development

- A way to improve children’s perceptions of a career in science with a view to aid future recruitment for the company

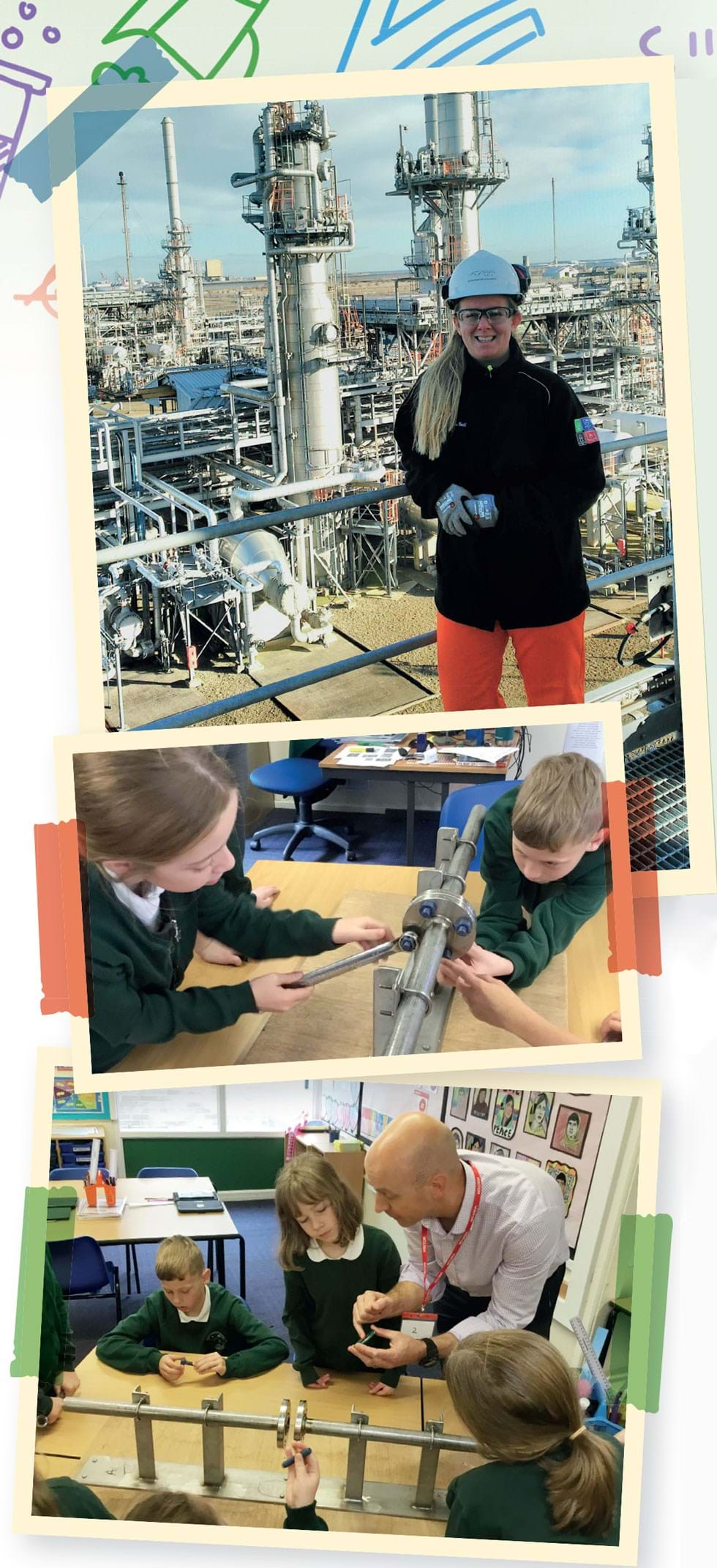

CCI Ambassador: Rebecca Ball Process engineer, Wood, CATS Terminal Teesside

Mackayla from CIEC provided our training, and explained what we could expect from the school visit to site, and the kind of language children would understand. She also gave useful examples of how the classroom activities relate to the things we could do on a site visit.

The most successful activity we have done on site is our bolted joints activity. The children learn how to make a flanged joint, the importance of having the correct bolts and gaskets for specific flange types and the advantages/disadvantages of this jointing method over other methods such as welding. They then make a flanged joint with small bore flanged pipework. This is always a hit, as the kids get the chance to be hands-on and learn through doing. You can tell when an activity has been successful by the number of questions you get asked. The more questions, the more engaging the session has been.

A big pitfall to avoid is talking at a level too technical for primary-age kids. It’s easy to slip into technical jargon they won’t understand, so being able to relate what we do at site to something they are more likely to understand will allow them to be more engaged.

My top tip for success is to relax. For engineers who don’t have children, it can be daunting to speak to a group of 11-year-olds. If what you say gets even one child to consider a career in STEM, then I would call that a success.

Why me? In 2022, women made up only 16.5% of all engineering roles in the UK.4 Being involved in the CCI programme allows me to represent this minority and show young girls that a career in engineering is an option for them.

I wish I had known about the variety of careers in STEM when I was at primary school. I think as a child you think you know what scientists and engineers are, but there are so many other career choices and many routes to get to those careers.

Teamwork: A variety of staff are involved in each primary school visit, and these are rarely the same. For example, at our last visit, we had me (process engineer), an operator, a mechanical technician, an operations engineer, an instrument engineer, and a mechanical engineer involved. This helps show the children that we work together as a big team rather than on our own. The aim of the site visit is to show them the variety of things we do on a daily basis, and how different disciplines have different ways of working. For example, engineers are the ones who come up with the solution and technicians implement that solution.

CCI Ambassador: Peter Huntley Shift Site Manager, PX Saltend Chemicals Park

The benefits of working with an organisation like CIEC is that most of the organisation is already done by them and we just host the visits. During the training from CIEC, we learned how to communicate with children on their level and in simple terms. This was an easy task as I currently have children approaching the age of the kids that we have hosted so far.

I feel that the children get the most out of the tour of the site when they see a relationship between the activities they have done in a classroom and what we do on an industrial scale. During the site tours, I ask the children if they remember the experiment when they learnt how to cool water. This is usually done just as we see one of our cooling towers where I then go on to explain that we use two pumps to supply cooling water to one of the production plants. Each pump moves approximately an Olympic-sized swimming pool of water every hour. I also let them know that each pump is powered by a motor of approximately 1,000 hp or the same as a Bugatti Veyron sports car. This usually elicits some wide open mouths and surprised looks.

My top tip is to keep the children engaged, as once you lose their attention they stop listening. Get a good Q&A session going. Be prepared – they do come up with some good questions, so you will need to ad-lib sometimes.

I enjoy sharing my experience of the workplace with the children. I enjoy giving a little back to the system in the hope that they do get a little inspiration from me. I usually start off by explaining a little about what I liked when I was at school and what I wanted to be when I was growing up. Once I feel I have their attention, I try to keep it on their level and relate to things they might understand more.

CCI Ambassador: Sarah Jones Project Operations Engineer, bp

We had a training session where we had a go at some primary science activities that were relevant to the work of bp. It was really useful to know what children are doing at this age in school and understanding the curriculum for Year 5–6 children. Mackayla then helped me to create my classroom session by suggesting how the activities are relevant to my own job. CIEC have made sure that the sessions we deliver are relevant to the age group. The structured sessions mean that both the children’s time and my time are used more effectively. Additionally, CIEC organise the sessions, we just turn up.

My top tips (having recently completed my training with CIEC) are: ensure sessions are interactive to get the children engaged; relate my work to the experiments they are doing; turn up with energy and enthusiasm, as the children will be interested to hear what you have to say.

To explain my job, I have used the activities from CIEC, such as filtering muddy water, exploring absorbent materials or making film-cannister rockets, and it has surprised me how I can use those to give a high-level overview of my work to this age range.

Why me? I would like to think that I’m giving back to the local area. There are so many opportunities in Teesside industry, and I’d feel really happy if just one child remembered that this was a career opportunity.

I think any interactions with schools are so much better when you’re supported by a scheme. I’ve done ad-hoc STEM presentations in the past, some with success, and some not so much. The best experiences I’ve had are when I’ve had someone who understands the knowledge level of the children helping me with the session.

References

1. www.york.ac.uk/ciec/cci/

2. https://bit.ly/4cIW2oT

3. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21227

4. https://bit.ly/441uUhj

This article follows on from the schools outreach articles featured in TCEs 992 and 994. You can access the previous articles at https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/features/category/education/

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.