Viewpoint: Heating Homes with Hydrogen – a Hazard that Should be Avoided

Tom Baxter’s TCE article “Home Hydrogen: Is it Safe?” generated a lot of interest from the chemeng community. Little did he suspect it would see him on stage at Ellesmere Port Civic Hall taking part in a heated public debate on the subject, a result of nearby Whitby being selected for a domestic hydrogen trial

I AM VERY concerned about proposals to provide hydrogen for household use. My concerns are twofold: safety and that hydrogen will put more families into fuel poverty.

As a time-served chemical engineer, I have been schooled in the principles of inherent safety (IS). Indeed, IS was a key part of my lectures on process safety at the University of Aberdeen and I was also fortunate enough to meet the father of IS, Trevor Kletz, and be influenced by him, when I worked for ICI.

Kletz described IS as “the avoidance of hazards rather than their control by added-on protective equipment” and espoused the simple concept of “what you don’t have, can’t leak”.

Inherent safety and home heating options

We know we can’t continue to burn fossil gas and the main options for low carbon domestic heat are hydrogen, heat pumps, and heat networks.

The latter two eliminate the risk of direct gas fires and explosions, the generation of harmful NOx and the indirect escalation of a house fire from hydrogen being present in the house. It should also be recognised that hydrogen is a global warming agent. The UK government published a report indicating that, over a 100-year timeframe, it had a global warming potential of 11 +/-5.

My own analysis concludes that heat pumps and heat networks are inherently safer than hydrogen. The pushback I often receive is that more people are harmed by electrical faults than gas. This is true but for this comparison it is about incremental risk.

Furthermore, let’s compare the inherent safety of natural gas with hydrogen. The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy’s Hy4Heat work showed that on a direct replacement basis, hydrogen was four times more likely to cause an injury. To bring the hydrogen injury risk to the same as natural gas required additional layers of protection – excess flow valves, increased ventilation, and outdoor location of meter.

To my mind, the need for those additional measures means that hydrogen is inherently less safe in a domestic setting than natural gas.

Cost vs safety

In industry you might elect not to use the inherently safer option because it may be more costly, possibly making the project non-commercial.

An example in my own industry, oil and gas, is whether to adopt a single offshore installation with process, drilling, utilities, and accommodation all supported by a single structure.

It would be inherently safer to install two bridge-linked installations separating the hazardous process, drilling, and utilities operations from the people, but this option is often not selected on cost grounds. A single, more cost-effective, installation is designed with additional layers of protection to bring the risks to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable).

So, is that the case with hydrogen – it will cost less?

Not according to numerous independent studies that show hydrogen to be a more costly option for the consumer. This work shows hydrogen to have a higher cost of ownership than electrification, with the subsequent knock-on effect of pushing more families into fuel poverty.

Discussing the pros and cons of hydrogen in a domestic setting

As I believe there is sufficient evidence available to dismiss hydrogen in a domestic setting, my view is that the residents of Whitby should never have been put in, what for many, was a very stressful position. Furthermore, the fact that the trials are taxpayer supported is a misuse of public funds in my opinion.

The Whitby trial was being organised by Cadent supported by Cheshire West and Chester Council and was one of two in the running to win the UK government contract to test hydrogen in 2,000 properties, alongside Redcar.

The Whitby residents had become increasingly frustrated by the actions of the council, government, and Cadent. They felt that they had been selected for a trial without engagement. They also felt that Cadent and the council were not listening to their concerns and that they were being provided with unbalanced information.

The Whitby residents had a Facebook book page for those concerned about the hydrogen trials and someone posted my TCE article. That initiated a chain of events for me – virtual sessions, technical clarifications, and support for media appearances.

What struck me was how angry the residents were at the authorities and Cadent. I was also very impressed at how the residents had educated themselves on the associated technical and commercial issues.

The residents also managed to garner a large media interest – interviews with Sky, local and national TV and radio, and coverage from The Times, Guardian, and other newspapers.

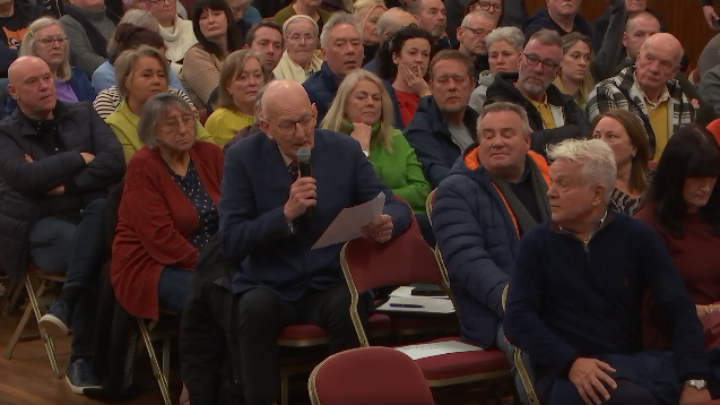

The residents were pushing for a vote and a public debate where their own views could be aired and, after both these requests were initially denied, the Whitby Hydrogen Village Engagement Session was convened in February at Ellesmere Port Civic Hall.

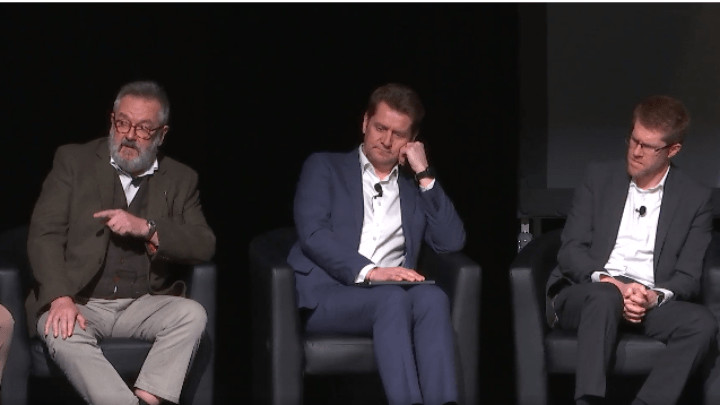

The residents presented their views, together with their chosen “experts” – Michael Liebreich (speaker, analyst, writer, advisor, and investor in the future economy), David Cebon (professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Cambridge) and myself. On the other side were Gordon E Andrews (professor of combustion engineering at the University of Leeds), Angie Needle (director of strategy at Cadent) and Mark Neller (director at Arup). The government representative did not attend but submitted a written statement. You can watch the debate here.

The sense of anger in the hall was palpable and the upshot was that the trial was cancelled by the government, with energy minister Lord Martin Callanan saying: “After listening to the views of residents it's clear that there is no strong local support.”

A win for the residents, and for me it was a pleasure to use my chemeng, technical, and business experience to help a community. And as an aside, another outcome of the TCE article was a meeting with the government’s chief scientist adviser for the Department for Energy, Security and Net Zero, professor Paul Monks.

What I learned from the experience and what would I do differently

I learned that the public do have a voice – but that needs organisation and perseverance. I learned that vested interests will resort to evasion and half truths to promote their interests. I also learned not to underestimate the ability of non-scientists to understand and evaluate complex issues.

I’m not sure I would do anything differently.

Challenging IChemE's stance on household hydrogen

In early January this year I approached IChemE regarding our position with respect to household hydrogen. Of all the professional institutions, I believe IChemE would be best placed to undertake a system-wide view of the options for domestic heating.

I was informed that “IChemE has not at this time published a specific position with regards to the use of hydrogen in domestic heating, or the safety implications thereof”.

Confirming the safety of domestic hydrogen was a topic up for discussion, they went on to say: “IChemE’s resources are unfortunately finite and the areas we work on must be prioritised according to available expertise, members’ needs and the degree of influence/value that can be achieved via the resource spent in an activity. The ultimate decision on these will be via the Learned Society Committee which calls on the advice of multiple areas within IChemE to approve work. I will ensure that your suggested topic will be part of their considerations in future work planning, but I can’t promise a specific outcome.”

I wonder what other members think about the hugely important household heating topic.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.