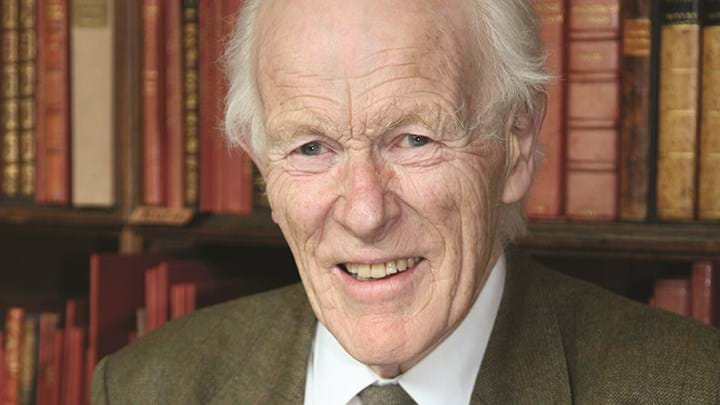

John Davidson, 1926–2019

JOHN Davidson, often referred to as a “founding father of fluidisation” in chemical engineering was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK on 7 February 1926 and died in Cambridge on Christmas Day 2019. He was proud of his North East roots and he could produce a convincing Geordie accent to surprised company. He recalled a bomb falling on the house next to his, which mercifully did not explode. With expertise in mathematics at his grammar school, John was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge towards the end of the War to read engineering (then mechanical sciences); and two years later he graduated top of his year. Industrial experience with Rolls Royce, and marriage to Susanne in 1948 then followed but by 1950 he was back at Trinity as a Research Fellow. Academically, a new opportunity opened up.

The first Shell Professor of Chemical Engineering (Terence Fox) was a man of great intellectual ability directed more towards teaching than research. He appointed John onto his staff in 1952 as a mechanical engineer and I followed in 1956 from physical chemistry. We had teaching duties but we also had much to learn.When Peter Danckwerts succeeded Fox he took the opportunity to strengthen the department’s growing reputation for research. John was the first to appreciate the fluid mechanics of a fluidised bed of particles: small bubbles rising through such beds are spherical but, importantly, at larger flows the bubbles are spherical-capped. John’s elegant work was beautifully confirmed by X-ray work at Harwell by Peter Rowe and his co-workers. John and I gathered a range of publications into a book entitled Fluidised Particles, published in 1963 by Cambridge University Press. It is the pride of my professional life to have been the junior co-author of that book. In 1966 John and I visited the Soviet Union and we discovered our book had been translated into Russian, without of course our knowledge, consent or royalty. Nevertheless we were treated handsomely during our visit. John was appointed Steward of Trinity in the late 1950s when the College undertook major work on its kitchens first built in 1605. Plainly the College judged that a highly intelligent engineer with problem-solving abilities would be a good interface between it and contractors. And so it proved. John was a busy man and, later, he was reluctant to allow “too busy” as an excuse for any shortfall in high quality work.

In 1970 John was IChemE President and we travelled with the then General Secretary, David Sharp, to Australia to attend Chemeca, an international conference arranged by IChemE and the Australian Academy of Science. Sharp was bemused in all our city calls down under we were generously greeted by former students. Thereafter, he always referred to his time in the hands of the “Cambridge Mafia”.

On 1 June 1974 there was a devastating explosion at Flixborough in Lincolnshire, UK, which killed 28 people and seriously injured a further 36. John was invited to join the Court of Inquiry and, after checking there would be no conflict with his plans to go to Australia in January 1975, he accepted. He found, however, that 70 days of public hearings meant that his future plans had to be put on hold. He did find the Inquiry intellectually absorbing and it provided material for some examination questions at Cambridge.

John received senior recognition from many learned societies, notably the Fellowship of the Royal Society (Royal Medal), the Fellowship of the Royal Academy of Engineering (Founder Fellow 1976), and recently IChemE’s creation of the John Davidson Medal to celebrate mentoring in engineering education, in which John excelled throughout his long life. He is survived by his children Peter (who read chemical engineering) and Isabel (who read law). He was a very good man, fondly remembered, and a great chemical engineer.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.