Ian Fells 1932-2025

Obituary of Ian Fells, a chemical engineer and 80s TV personality whose leadership on energy helped shaped the transition away from fossil fuels

IAN FELLS, a beloved chemical engineer and 80s television personality, has died at the age of 92 after a long illness. A lifelong energy expert fondly remembered as a judge on the BBC’s science television programme The Great Egg Race, Fells was also an early advocate for renewable energy and was known as a committed proponent for nuclear power right up until he became too ill to work.

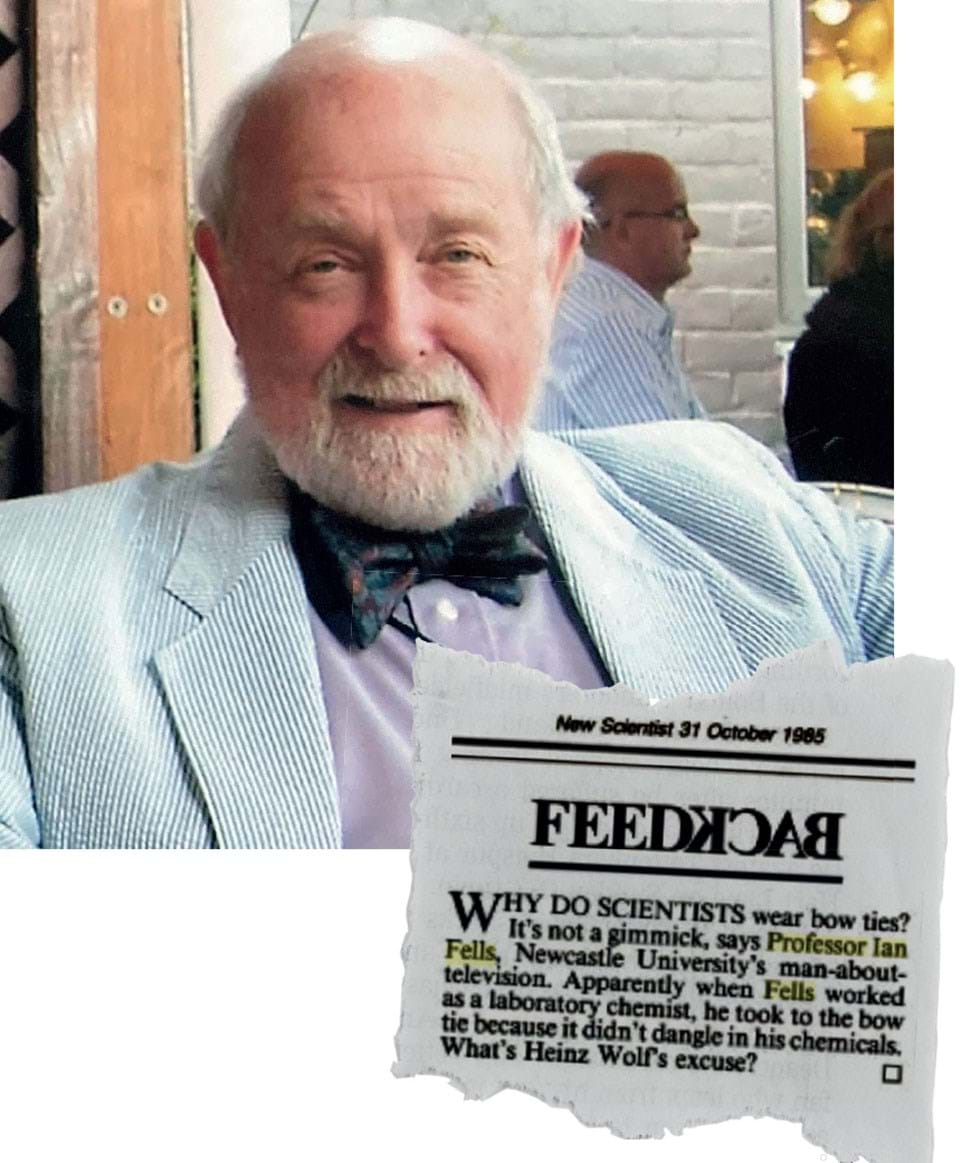

Born in Sheffield in September 1932, Fells spent the war years in the city which was heavily bombed during the blitz. His father Henry Alexander Fells was a fuel engineer working mostly in Sheffield’s large steel industry. Fells’ four sons, Nick, Alastair, Jonathan and Cris, have all followed the “family tradition” of engineering. “It must have been the influence of my father,” says Nick who followed his father’s footsteps particularly closely, studying chemical engineering at Trinity College, Cambridge, Fells’ own alma mater. Nick also wears a bowtie when conducting HAZOP studies, mirroring Fells’ signature TV look and emphasising the importance of the bowtie model in process safety.

Between school and Cambridge, an 18-year-old Fells joined the Royal Corps of Signals to complete his National Service. One of his competency tests was to put together a disassembled Sturmey-Archer bicycle hub against the clock. “He hid the tiny components in his beret,” Nick recounts, which “bamboozled” the officer in charge. Fells was duly promoted to signalman first class, later commissioned and sent to serve in

Austria.

Nick says that the importance of occasionally breaking the rules was one of the most valuable lessons his father passed onto him. In another army test in which he and his team had to scale an eight-foot-high electric fence with a barrel of gunpowder, Fells displayed further initiative by leaning a scaffold pole against the fence and “declaring it to be earthed”, compelling the officer in charge to reluctantly sign the squad off with a pass.

Fells studied natural sciences at Trinity, publishing his PhD thesis on reaction kinetics in 1959. After a short period lecturing at Sheffield University, Fells moved to Newcastle- upon-Tyne in 1963 to join Newcastle University’s chemical engineering department in its inaugural year, settling in the Gosforth area of the city. At the time of his death he remained emeritus professor of energy conversion at the university.

Fells became well-known for his television appearances, his first in 1965 on the BBC’s science and technology show Tomorrow’s World. He held a deep belief that scientists and engineers possessed a “duty” to “explain what we are on about to the public”, as he explained many years later.

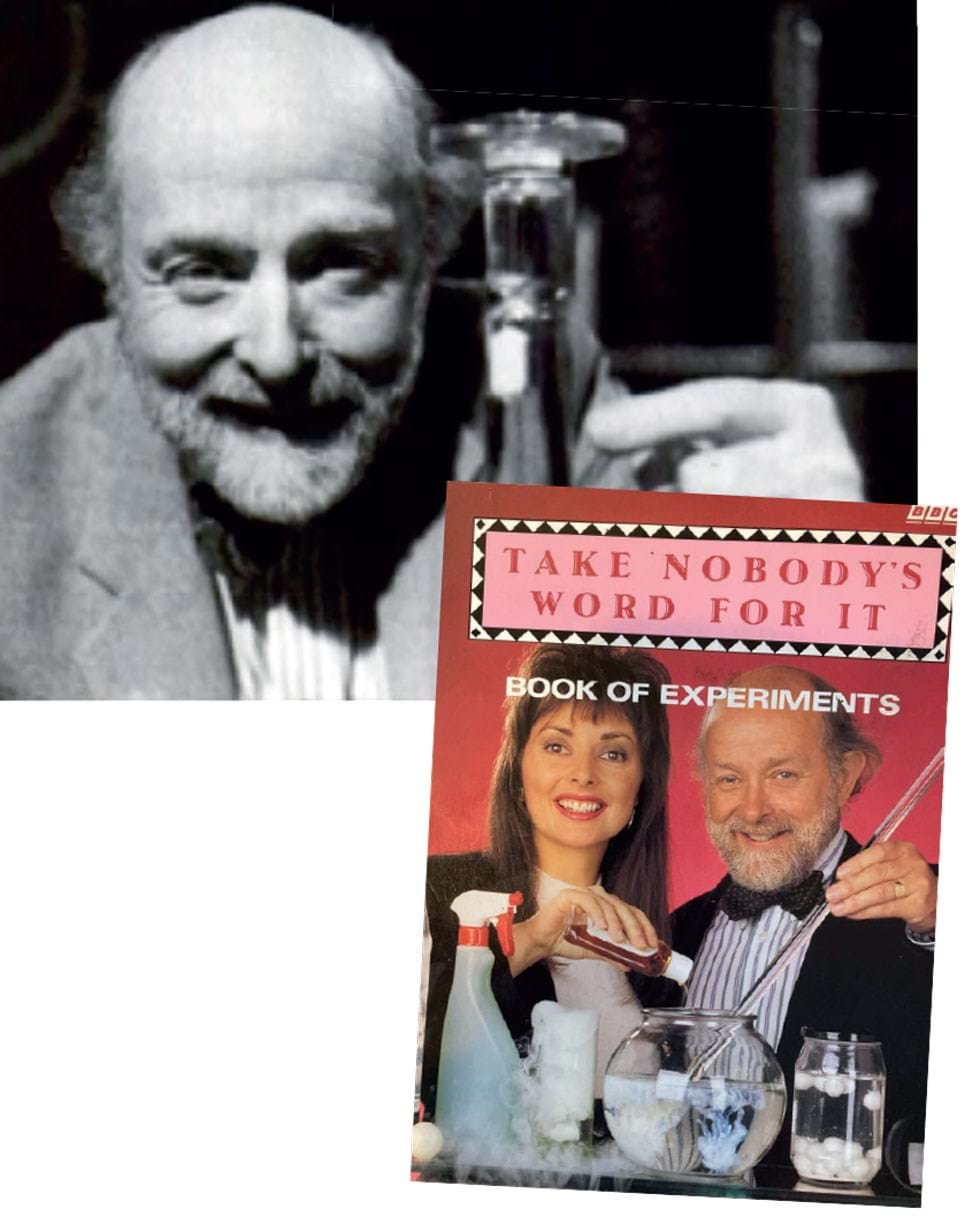

In 1979, he joined Heinz Wolff as a judge on the BBC programme The Great Egg Race, serving until 1986. The show invited amateur inventors to create quirky devices such as automated tea-makers, which Wolff and Fells would judge while playing up to their mad inventor caricatures. At one stage, the programme became a family affair when, unbeknown to Fells, his wife Hazel entered an all-female team under their maiden names, aggrieved by the programme’s male dominance.

Fells held a deep belief that scientists and engineers possessed a “duty” to “explain what we are on about to the public”

Fells went on to co-host BBC science documentary series Take Nobody’s Word For It alongside Carol Vorderman, including one episode with then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher in which she showed viewers how to whisk eggs properly.

Away from the limelight, Fells was an early advocate for the energy transition. When serving a year-long term as president of the Institute of Energy in 1979, he explained the organisation’s recent name change from the Institute of Fuel, writing in the in-house magazine Energy World that “times have changed and our concern must now also include nuclear energy, renewable energy resources such as wave, wind and tidal power, solar and geothermal energy, the economics of energy conversion processes and of course, energy policy”. To that end, throughout his life he advised a number of government and international committees on energy policy, returning each time despite his frequent disappointment about the decisions politicians ultimately made on nuclear power. Forever frustrated with the tone of political discussion around scientific matters, Fells once described his mission as to “introduce a little reality” into the energy debate. His services to energy technology and policy earned him the British honour of CBE in 2000.

As the energy transition gradually shifted into mainstream consciousness, Fells continued to issue prescient commentary. Writing in The Guardian in 2008, he warned that achieving the European Union’s goal that 15% of all final energy consumption be provided by renewables by 2020 would require an “expensive miracle”. The UK ultimately fell short of the target by 1.4%, while rising energy prices and sluggish demand have led to a recurring trend of low-carbon projects being scrapped in recent years.

Fells nonetheless remained committed to the development of clean energy and was active as technical director of Penultimate Power UK, consulting on fourth generation modular nuclear reactors.

Ian died in his sleep in hospital in Newcastle on 20 August 2025, just two weeks short of his 93rd birthday, after suffering from multiple conditions for several years. At the time of his death he was still living in the family home in Gosforth. His first wife, Hazel, died in 2018 and he is survived by his second wife, Candida.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.