Five minutes with… Health Researcher Hannah Leese

Adam Duckett speaks to the Nicklin Medal winner about needles and nominations, and discovers that both can be positive…and pain free

CHEMICAL engineering unlocks the gate to far-reaching fields. I know this. I suspect you already know this too. Yet, like me, I hope you still find yourself struck by the rich variety of new pastures in which chemical engineers can be found striving for progress.

Hannah Leese of the University of Bath is a case in point. Because Hannah has literally stepped into that ever-expanding field and asked “how could we use biotechnology to turn this pasture grass into human food?” A few paces on in this imaginary innovation space and Hannah’s exploring how 3D-printed microneedles can painlessly tip off a patient that they ought to seek out a cancer screening. Striding further in, we also find Hannah investigating how electrospinning could enable the health sector to engineer tissue implants that are perfectly personalised for the patients that so desperately need them.

“Chemical engineering and biochemical engineering enable healthcare impact. And I think this is the thing that I love the most about chemical engineering,” says Hannah, a reader in chemical engineering at Bath.

It was Hannah’s work on microneedle technology that won her IChemE’s Nicklin Medal in 2021. The medal was introduced in 2014 to recognise talented chemical engineering researchers, and is named in honour of Don Nicklin, the longstanding head of chemical engineering at Queensland University who was known for supporting up-and-coming researchers.

Painless at point of production

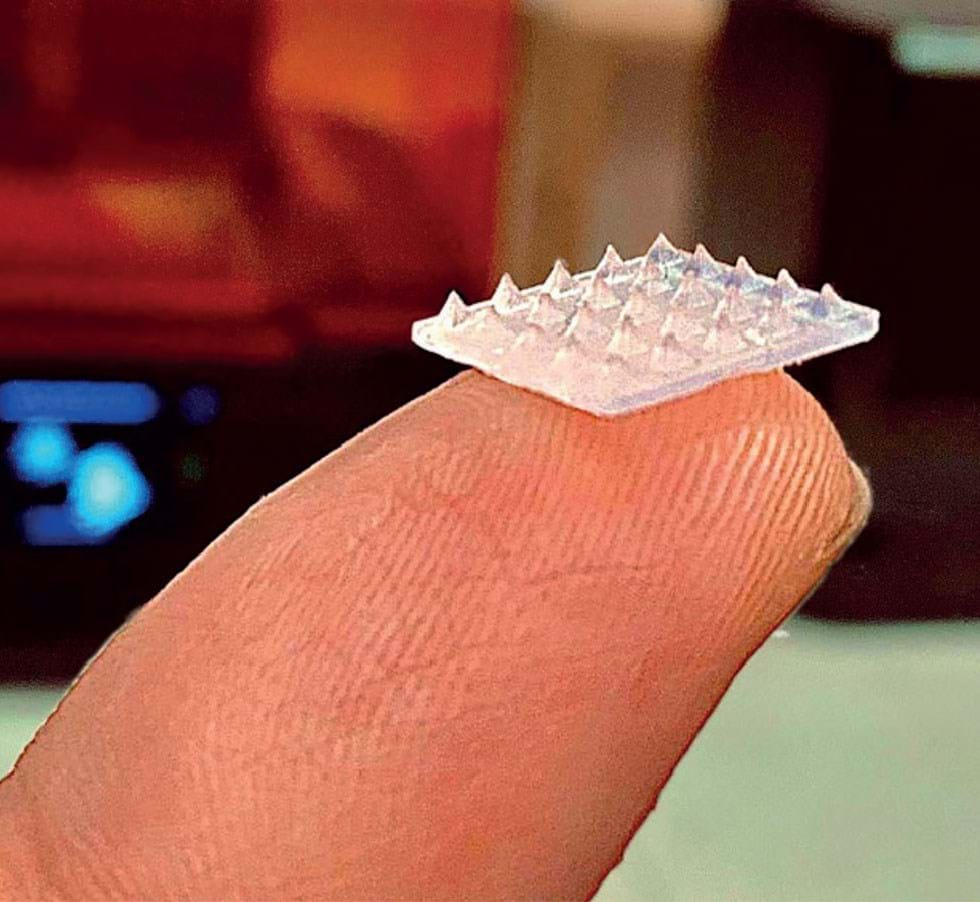

Hannah and the researchers she’s collaborating with are looking at how we can move away from conventional manufacturing approaches – “Microneedles have been manufactured in quite an expensive way historically. And some of them were not very small.”

Abandoning the metals that have been typically used, they are developing 3D-printed multifunctional microneedles that can be made at the point of use.

“What we’ve focused on is printing polymeric-based microneedles. It makes the technology very, very accessible.

“We use the 3D printer to make what we call solid microneedles. That uses the outside of the microneedle for sensing different biomarkers. We’ve made them conductive so we can sense different small molecules such as cortisol and glucose.”

Hannah’s team has also printed hollow microneedles that use capillary forces to take up so-called interstitial fluid from just beneath the first few layers of skin and then pass the markers to a lateral flow test that can indicate whether the inflammation is of concern. Ultimately, it could help in the early detection of sepsis and cancer.

“It’s not very quantitative, but it’s very important from a qualitative point of view. It can say ‘these levels are quite high. Go and see somebody.’” Hannah predicts the technology will find use in around five years.

“What we envisage is that these microneedles could be used by the GP and in the pharmacy.”

As well as decentralising production and tailoring it for specific skin types, the use of microneedles and their capillary action also eliminates the need for batteries and pumps and should eradicate the physical pain of having your blood drawn by needle for these sorts of diagnoses.

“Microneedles in general are pain free because they’re not very long and they won’t, and they should not, hit the pain receptors under the skin.”

If they are pushed with too much pressure, however, they still can hurt, so there’s work needed to help educate those who will use them.

The team is also looking at how the technology could be used to administer antibiotics, and for monitoring babies during childbirth. “It won’t be invasive for the child and will enable us to check oxygen levels so that’s super exciting.”

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.