Transition to low-carbon world needs to be faster, says DNV GL report

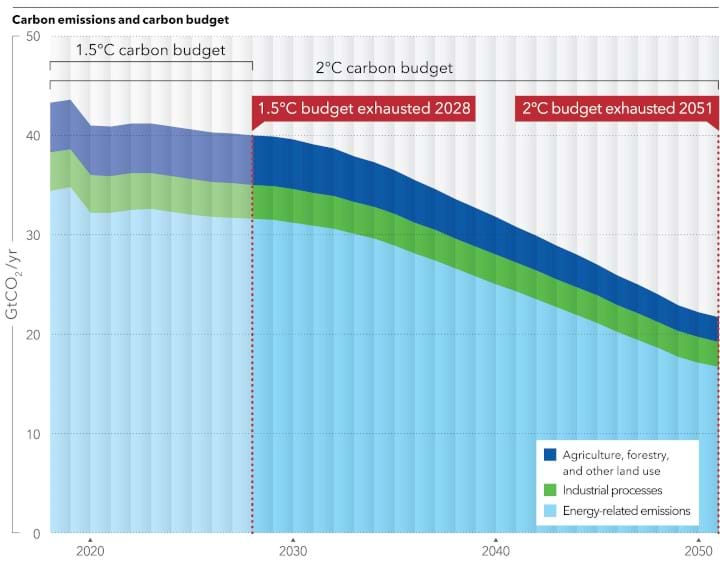

ENERGY-RELATED CO2 emissions have peaked due to the pandemic, but the world is still on track to exhaust the remaining CO2 budget by 2028, according to DNV GL’s 2020 Energy Transition Outlook.

The fourth annual outlook from DNV GL is a forecast of how the energy transition up to 2050 will take place, based on current trends. A key area of focus in the 2020 outlook is the influence of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Energy-related emissions have peaked

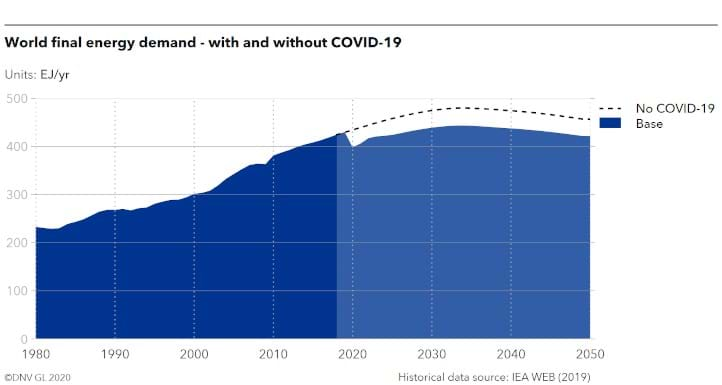

The pandemic has caused an 8% drop in energy demand this year. Recovery will be slow and behavioural shifts such as home working will have a lasting effect. The outlook calculates that energy demand will be 6–8% lower each year to 2050 compared to what it would have been if the pandemic didn’t happen. Global energy demand will peak in 2034 at only 4% higher than current levels and will then decline gradually.

The drop in energy demand will be partially due to increased electrification such as the switch to electric vehicles, and also increased energy efficiency. Electrification makes up less than 20% of the energy mix today, but will almost double by 2050.

Despite energy demand not peaking until 2034, emissions from energy will not continue to rise, partially due to the growing share of renewables in the energy mix. Emissions are expected to be 8% lower this year due to the pandemic, resulting in energy emissions likely having peaked in 2019. This brings peak energy emissions forward by five years compared to the previous forecast. There will be some lasting effects of the pandemic in sectors such as air travel, and this will result in 75bn t less of CO2 emitted by 2050. However, this drop in emissions is not significant enough to help meet the Paris Agreement goals, and a similar drop in emissions would need to occur every year to 2050 to meet the 1.5oC target.

“Clearly that is not sustainable,” said Remi Eriksen, CEO of DNV GL, at the launch of the Outlook. “Emissions reductions this year have come at enormous cost in lives and livelihoods. We can’t empty the airliners twice, so how can we get further emissions cuts in the future? There really is an enormous challenge ahead to find ways to decarbonise that are economically sustainable and make a positive social impact.”

Oil demand will fall

Oil demand is expected to reduce by 13% for 2020, leading to 2019 being the most likely peak for oil. Oil demand would have peaked in 2023 and declined gradually if it wasn’t for the pandemic. This broadly agrees with this year’s BP Energy Outlook, which models three different potential scenarios. Only under its “business as usual” scenario would oil demand plateau in the early 2020s and decline slightly to 2050. In its “rapid” and “net zero” scenarios, oil demand does not recover from the impact of the pandemic, instead falling by 50% and 80% by 2050 respectively.

The DNV GL report notes that concerns about employment will likely extend pro-extraction policies, however in the longer term, skill sets and expertise will be transferred to other areas in industry.

Coal peaked in 2014, and coal use in 2050 will be less than a third of current levels, despite the rise for coal demand in India and a flattening of coal use in China.

Natural gas will become the largest source of primary energy in 2026, peaking in 2035. Decarbonisation of gas through measures such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) will be slow, with only 13% of gas decarbonised by 2050. Hydrogen production will be dominated by steam methane reforming until 2035.

In 2018, around 8% of global fossil fuel supplies were used for non-energy purposes, with petrochemicals being the largest consumer of fossil fuel feedstocks. Around 45% of these feedstocks were used to produce plastic in 2018, and this is expected to rise to 60% by 2050. Plastics demand will continue to grow, but the rate of recycling will grow faster, improving from 13% to 47% by 2050. The use of fossil fuels as a feedstock will peak in 2033 before declining rapidly. Oil will continue to dominate as a fossil feedstock, accounting for around 50% of the feedstock mix by 2050. Bio-based feedstocks will only become a competitor in the long term, and only with strong policy support.

Wind and solar power will provide 24% of the world’s electricity in 2030 and 62% in 2050, with solar PV capacity growing 20-fold and wind 10-fold. Speaking at the launch, Peter Raftery, Global Head of Technical and Commercial Asset Management at Blackrock, commented that the growth of renewable energy was really the “low hanging fruit” in terms of decarbonisation, and areas like shipping and long-distance transport will be harder to tackle. He pointed out that even in electricity generation, renewables have a long way to go. He gave an example from that morning, where 10 GW of natural gas-fired power was switched on at the Great Britain power grid over a two-hour period to cope with the daily ramp up in demand. “Renewable energy has got some distance to go before we can replace that type of flexibility, but that is the next challenge.”

World on track for 2.3C warming

Even with a drop in emissions, growth in renewables, improved energy efficiency, and increased electrification, decarbonisation is not happening fast enough. According to the Outlook, the world is currently on track to exceed the 1.5oC carbon budget by 2028, and the 2oC budget by 2051, only reaching net zero emissions by the end of the century. At that time, temperatures will have increased 2.3oC from pre-industrial levels.

“That level of warming is considered dangerous by the world’s scientific community,” said Eriksen. “For the sake of future generations and the wellness of our planet, we must have a faster transition.” He said that while it is not known exactly what impact the level of warming will have, the effects such as sea level rises, droughts, wildfires, and flooding will lead to billions of people not being able to live where they live today.

Getting on the right track

There is no single solution to getting on the right track, and a combination of different solutions will be needed, with focus on energy and carbon-intensive sectors. The report says that the Paris Agreement goals can be reached with existing technology at sufficient scale.

Under the current trajectory, the uptake of CCS will be limited and it will only accelerate in the 2040s, capturing 11% of energy-related emissions by 2050.

Speaking about the shipping industry, Andreas Sohmen-Pao, Chairman of BW Group, said: “People are trying hard to look for the new solutions and new fuels. As an example, we are investing in methanol and biofuels, and we’re studying ammonia. The challenge is that there is a very big price gap.”

A strong policy push is needed to drive down prices of existing solutions and therefore drive decarbonisation.

Claire O’Neill, Managing Director for Climate and Energy at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, noted at the report’s launch there is always talk about national governments leading on policy, but that we don’t focus enough on local governments such as those in cities, states, and regions. She said that in the UK, local politicians have more power to implement changes such as local energy schemes.

Ivor Catto, CEO of Renewable Energy Systems (RES), said that unlike the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, things will be different with pandemic recovery in terms of dealing with the climate crisis. “The difference is before 2008 climate change, and tackling climate change, was inconvenient in that financial pressure was the bigger pressure of the day.” He said that as Covid-19 is something affecting all countries at the same time, it shows how the whole world can respond and work as one to tackle a challenge.

Tina Bru, Norwegian Minister of Petroleum and Energy, said: “We need to provide energy to sustain a growing world population and improve the standards of living for billions of people globally. At the same time we need to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. These challenges must be solved in parallel.”

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.