Storing energy brick by brick

FIREBRICKS similar to those used to line kilns for over 3,000 years could provide an industrial energy storage solution to address issues of intermittent renewable power, according to researchers at MIT.

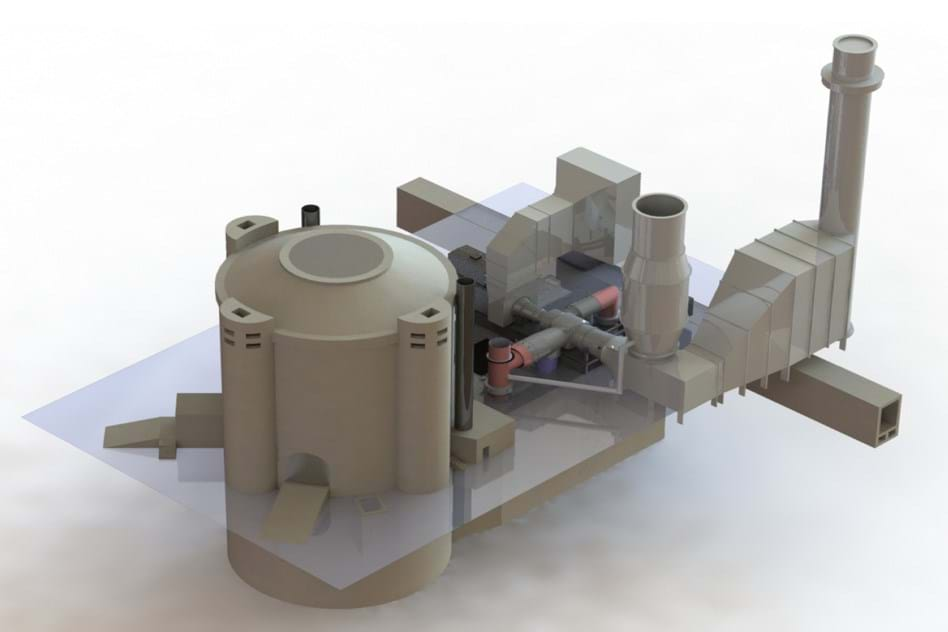

The system, called FIRES (Firebrick Resistance-heated Energy Storage), was described in a paper that appears in this week’s Electricity Journal.

The team hopes to use excess energy when demand is low, such as when wind power generation is high on a stormy night, to heat up large masses of firebricks in an insulated casing.

Such bricks are simply variants of ordinary bricks, made from clays capable of withstanding temperatures of 1,600°C or more. They retain heat well, which the researchers hope can be released at a later time by blowing air through channels.

Since the demand for industrial heat often exceeds demand for industrial electricity, this heat could then be used directly for industrial processes, or could feed generators that convert it back to electricity if needed.

Charles Forsberg, a research scientist in MIT's department of nuclear science and engineering and lead author of the paper, hopes that FIRES could help stabilise the market price for electricity, which can suffer from strong fluctuations.

“In electricity markets such as Iowa, California, and Germany, the price of electricity drops to near zero at times of high wind or solar output,” Forsberg said.

In the paper, he says that while the basic FIRES technology could have been developed and deployed in the 1920s, it is this change in the electricity market that creates the incentive to deploy FIRES.

FIRES is expected to be most efficient using electric resistance heating, as the cheapest device for using electricity, and ceramic firebricks, which are low-cost, durable and have large sensible heat storage capabilities.

The paper concludes that for some applications requiring temperatures of 500-700°C, such as producing steam or heating hydrocarbons in refineries and chemical plants, FIRES can be built today. However, the current limit on FIRES is the resistance heaters, with existing low-cost, reliable heaters only being capable of heating to 850°C.

Forsberg hopes to set up some full-scale prototype units in real-world conditions by 2020, which are likely to be in collaboration with a company such as an ethanol refinery, which uses a lot of heat, located near a sizable wind-turbine installation.

Electricity Journal: http://doi.org/cctc

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.