Fatal dam breach in Brazil leaves hundreds missing

A TAILINGS dam in Brazil has collapsed, leaving a reported 16 people dead and 297 missing. Other sources put the death toll closer to 40. The dam, known as Dam 1, was part of the Córrego do Feijão mine, located in Minas Gerais, and is mining company Vale’s second dam in Brazil to fail in just over three years.

Rescue efforts are currently underway, and medical facilities and help centres have been made available to those affected.

Tailings are the waste left behind from processed ore. The rock is crushed and ground up and put through a chemical process to recover the valuable component, resulting in a slurry made of fine uneconomic rock and chemical effluent that is stored in tailings dams.

The breach occurred on Friday and caused the release of a muddy slurry which buried the surrounding area. The effects of the breach reached the nearby community of Vila Forteco, Brazil. Those affected include Vale employees, contractors, and members of the community.

The cause of the breach is not yet known. Fabio Schvartsman, CEO of Vale, said that the company would aim to find the cause quickly and take the necessary measures to solve the problem, but that its current priority is to help those affected.

Reuters reports that on Saturday, Brazil’s National Mining Agency ordered Vale to halt operations at Feijão.

At 05:30 on Sunday sirens alerted that another dam had overflowed. Water levels at Dam 6 increased because of the breach at Dam 1. At that point rescue efforts were halted and as a preventative measure the local community was moved to emergency meeting points. The dam is being drained using pumps and the critical level has already been reduced from 2 to 1, allowing rescue efforts to continue and the local community to return to their homes.

Preventative measures

Dam 1 was an iron ore mining tailings dam which was decommissioned in 2015. The dam has a capacity of 11.7m m3 and when it was breached, contained silica. “Basically, it is soil,” said Schvartsman.

In comparison with the 2015 Samarco dam collapse, the environmental effects of this breach are expected to be minimal. Fundão, which was located in Mariana, Minas Gerais, Brazil, collapsed due to design flaws. The failure caused a mudslide which buried villages and homes, killing 19 and polluting local water supplies. Miner Samarco is jointly owned by BHP Billiton and Vale.

After Fundão collapsed, Vale brought in changes aimed at preventing a similar incident, including: periodical dam safety reviews by specialised companies (national and international); detailed emergency action plans; external audits; implementation of modern warning systems, with sirens for emergencies; and population registrations.

There were sirens in place at Dam 1 and when asked if they had worked, Vale CEO Fabio Schvartsman said: “Not even we know. Probably they worked but because it happened so fast, it was ineffective. The breach was too violent, too fast.”

Schvartsman became CEO of Vale in 2017, two years after Fundão collapsed. When he took over, he intended to stop repeat incidents, suggesting that Vale change its motto to “Mariana, never again”. Reminded of this motto during a press conference on Friday, he said he was “completely torn apart”.

Schvartsman claimed that the dam breach came as a complete surprise for the company. Following inspection in July and September 2018, TÜV SÜD, an international company which specialises in geotechnics, determined that Dam 1 was safe and stable. “Nobody knows what happened,” said Schvartsman.

The upstream method

Stephen Edwards, deputy director of the University College London Hazards Centre said it is difficult to speculate on the cause of the dam failure, even more so given that the company has declined to address questions on the expected cause to instead focus on the ongoing humanitarian effort.

“There are a number of reasons why a tailings facility will fail,” said Edwards, who has worked in South America on the impacts of tailings, including a visit last year to the site of the Samarco disaster.

“This one was inactive so it may be that there was an inherent weakness in the foundation, in the actual dam itself”.

The dam was built using the upstream method. The face of the dam is not built in a single phase as with a hydroelectric dam, instead the face is built up in stages as the tailings are added and their depth increases. The face of the dam is built from the coarser portion of the tailings themselves and is built over the finer slurries it is designed to hold back.

A 2014 study on tailing dams and their failures reported that many failures are likely to go unreported due to legal and reputational concerns. The researchers estimate that the rate of failure could be as high as one in 700 tailings dams compared to one in 10,000 for water-retaining dams.

“The upstream method is the worst… because of the potential likelihood of failure of that design”, Edwards said.

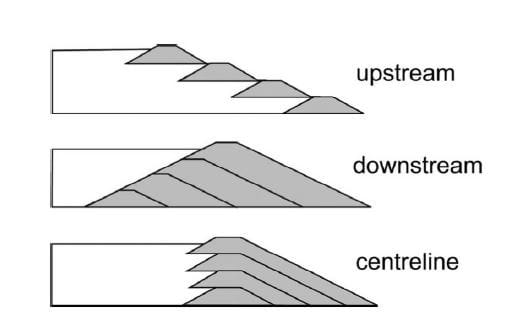

Edwards commented that industry opts for upstream dams over more resilient centreline or downstream methods (see Figure 1) because it's “basically quicker to build and cheaper.”

David Chambers, founder of the Center for Science in Public Participation, which provides technical assistance on mining, said Chile is the only country that prohibits the use of upstream dam construction and has pushed for it to be banned more widely.

“The use of upstream tailings dam design should be prohibited in areas where net precipitation exceeds net evaporation, and in areas where the risk of seismic shaking is moderate or greater. Upstream tailings dams have demonstrated that they pose an unacceptable level of risk of failure in these areas,” he said.

Removing water from tailings stabilises them, but keeping the water content high helps with logistics.

“The problem is to get the tailings to actually flow from the processing plant [through pipes and canals] to the storage facility they need high fluid content so that they are mobile,” Edwards explained.

Systems commonly in place to remove water at the dam are internal drainage systems to dewater the tailings and overflow pipes to decant any excess rainwater falling on the surface.

Edwards said there is a lot of work underway to try and produce tailings more as a thick paste and also to dry stack them but these are not yet widely used.

“Traditionally we’ve used slurried tailings and it’s just easier to keep using that mechanism of transport and disposal, especially in countries where you’ve got access to plenty of water. But I think events like we’ve had on Friday…there has to be a culture of change in the way we treat and manage tailings.”

Looking at the issues from a wider social standpoint, Edwards noted that as demand for resources increase and the grade of ores being processed diminish, the volume of tailings is set to increase.

“We have to be mindful that what we acquire, and use does have an impact globally, and unfortunately these tailings failures are one of the worst kinds of impacts of our demand for these mineral commodities.”

Effects on other structures

Dam 6, which overflowed because of the Dam 1 breach, contains 843,800 m3 of mine tailings. It was inspected following the breach and found to be within required safety parameters, even after the impact of the tailings.

Dam 6 is now being monitored by two radars, one of which works with real-time monitoring every three minutes.

The breach of Dam 1 also affected small-structures B4 and B4A of the Córrego do Feijão mine. Dam 7 and Menezes 1 and 2 were not impacted.

Rescue efforts

Following the breach of Dam 1, Vale mobilised 40 ambulances and a helicopter to help in the rescue. In addition, 50 communication radios are operating and balloons equipped with infrared and wi-fi have been contracted for aerial monitoring.

Rescue and care of the wounded is being carried out on site by the Fire Department and Civil Defense. Private and public hospitals are working to help those affected, and three help centres have been established. Employees and volunteers in the help centres are working to receive and identify victims.

Vale has provided 800 people with accommodation, water, and food.

Financial repercussions

Following the incident, judges have approved the seizing of R$11bn (US$3bn) from Vale’s bank account, and decided that Vale must take the necessary measures to reassure the stability of Dam VI, and help those affected.

Vale has also been informed of administrative sanctions worth R$349m.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.