ChemEngDayUK: Pandemics, project-based learning and skills

Chemical engineers share research on global challenges

MORE than 200 chemical engineers met at University College London (UCL) in April to share their research focused on addressing global challenges and to take part in workshops on teaching practices and researcher careers opportunities.

Organised and hosted by UCL’s departments of chemical and biochemical engineering, ChemEngDayUK returned for its first physical meeting since Covid-19 struck. I was told that the level of engagement had surpassed expectation, and evidently the discipline has much to be positive about given the breadth of research topics being shared by departments from across the country. This included Claire Adjiman, Director of Imperial College London’s Sargent Centre for Process Systems Engineering (who gave the opening plenary on engineering molecules for better processes), and shorter talks given by early-stage researchers and academics on topics as varied as machine learning for vaccine production and optimisation; sustainability in brewing and distilling; using molecular simulations to design sustainable membrane separations; and reducing the environmental impacts of culture media for lab-grown meat.

Race to scale up and scale out

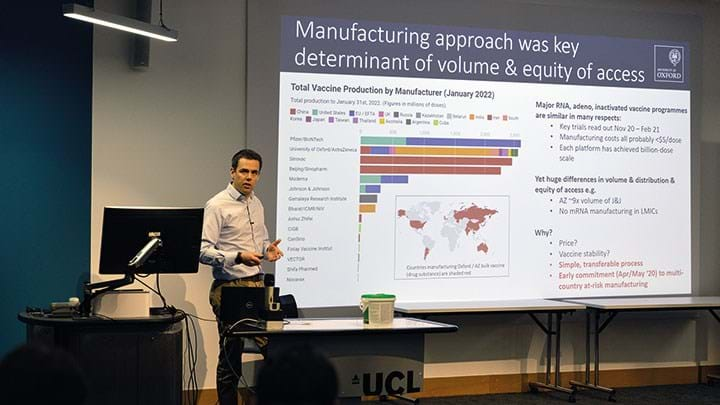

If there is one story that captures the importance of process engineering in recent years, we must surely return to Covid-19 and the extraordinary efforts that were required to rapidly scale up and scale out the manufacture of cutting-edge vaccines. So it was fascinating to hear Sandy Douglas of the UK’s Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford describe the challenges his team and their collaborators overcame in the race to manufacture the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

The team had a vaccine manufacturing platform that had successfully produced Ebola vaccine, and the university had clinical trial experience but they were worried that an outside funder or industrial partner would consider their work an academic curiosity.

Douglas outlined some of the key twists and turns that culminated in 2.5bn doses of the vaccine being produced by January 2022

“We thought we could make a vaccine, we thought we could test it, but we had a glaring gap in our capability – we had only ever made a few hundred or a couple of thousand doses of any of our vaccines.”

Starting with just a 3 L scale production, Douglas outlined some of the key twists and turns that culminated in 2.5bn doses of the vaccine being produced by January 2022. There was the mailing list request to find scaleup partners; a rush by car to get cells to contract manufacturers; the shortage of doses that hampered clinical trials; the removal of a tangential flow filtration step to debottleneck manufacturing; the risks taken to run activities in parallel including booking production facilities and materials long before the process was finalised; and centralising a programme for continual process improvement to ensure separate manufacturers across the world achieve consistent production.

Douglas is clearly proud of what he and his partners have accomplished, and particularly the equity achieved by producing the Oxford/AZ vaccine in so many more low- and middle-income countries. “It’s been an amazing story of academic-industrial collaboration.”

Yet he ended the talk with a note of caution: “I can tell you a nice story about just-in-time process development. The less positive spin is that manufacturing slowed everything down, every step of the way.” He called for government to be prepared. “We need them to be funding warm-lit facilities, on standby, with the materials ready to go. We need them ready to step in and place orders as soon as the pathogen is on the horizon for at-risk manufacturing.”

A different teaching philosophy

The conference was bookended by two workshops organised by IChemE’s Education Special Interest Group: one on the capstone design project with discussions on accreditation requirements, the design skills industry is looking for in graduates, and educators sharing their design project approaches. The second was organised by lecturers Elton Dias from UCL’s chemical engineering department and Chika Nweke from UCL’s biochemical engineering department. Dias led a three-hour workshop outlining UCL’s use of project-based learning and helped teachers from other departments plan how they might also put it to use.

As part of its Integrated Engineering Programme, which involves teaching fundamental technical knowledge in tandem with interdisciplinary, research-based projects and professional skills, UCL uses so-called Scenarios that involve project-based learning. UCL students complete six of these scenarios during their degree and each takes a full week. In essence, students are presented with a real-life problem and are required to work in teams to solve it. UCL’s Scenarios are designed in such a way that they cover several learning objectives for example related to thermodynamics and transport phenomena but wrapped up in a topical subject. Dias said he has seen Scenarios themed around the hydrogen economy really inspire his students.

Nweke said: “The design project in their final year is more is more of a research adventure. It’s a lot more open-ended. You could see project-based learning as mini design projects. But with more specific targets in terms of students learning particular technical skills that will build them up to that third-year project.”

Students are presented with a real-life problem and are required to work in teams to solve it. UCL’s Scenarios cover several learning objectives

Dias said: “It is more at the entry level but the students learn some technical content, they get to apply that content to a real world example, and then we can close that chapter.”

The activity involves working in teams, requires self-learning and critical thinking, and attending mock client meetings, all of which help to build durable professional skills.

Asked what benefits they’ve seen from this approach, Nweke mentions the employability of the students though both lecturers smile as they recall that it takes a while for the students to appreciate the approach.

Nkeke said students have contacted her to say they didn’t enjoy going through the process but recognised how useful it had been when they had been asked at interviews if they can demonstrate how they’ve dealt with team dynamics, project management and leadership skills. “They really appreciate it when they go out into the real world.”

EdSIG chair Esther Ventura-Medina said the SIG wanted to raise awareness about the use of project-based learning because the emphasis and philosophy are quite different to the more closed problem-based learning commonly used elsewhere. She asked that any readers interested to learn more about the approach should contact the SIG directly.

Early career researcher workshop

After the event I spoke to UCL lecturer Vasileios Charitopoulos who co-organised a workshop with colleague Paul Dalby on the future career opportunities available in a rapidly changing world.

“The workshop covered PhDs to postdocs who are trying to navigate in their transition, either for staying in academia or moving towards industry,” said Charitopoulos. “In the last few years, we’ve also seen a big trend of skilled researchers opening their own companies and commercialising their research.”

Topics covered during the panel discussion and audience interactions included a debate over whether industrialists are put off from hiring post-docs who spend too long in academia; how systems thinking and coding skills make chemical and biochemical engineers attractive to industries looking to manage competition from disruptive technologies and rivals; how supervisors should commit to supporting postgraduates with their career development, and how departments could provide bridging funding to help post-doctoral associates experience funding applications and work towards academic independence; and if you think there is commercial potential to your research speak to your university’s intellectual property team as early as possible to help protect it.

“We as a profession are in a very lucky position,” Charitopoulos said. “The spectrum of opportunities available open up endless career choices.”

Next year’s ChemEngDayUK will be hosted by Queen’s University Belfast.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.