The Novelist Looking for a Chemical Engineering Reaction

Aniqah Majid finds out how a workshop promoting literacy to chemistry students is aiming to fuel a surge of highly communicative chemical engineers

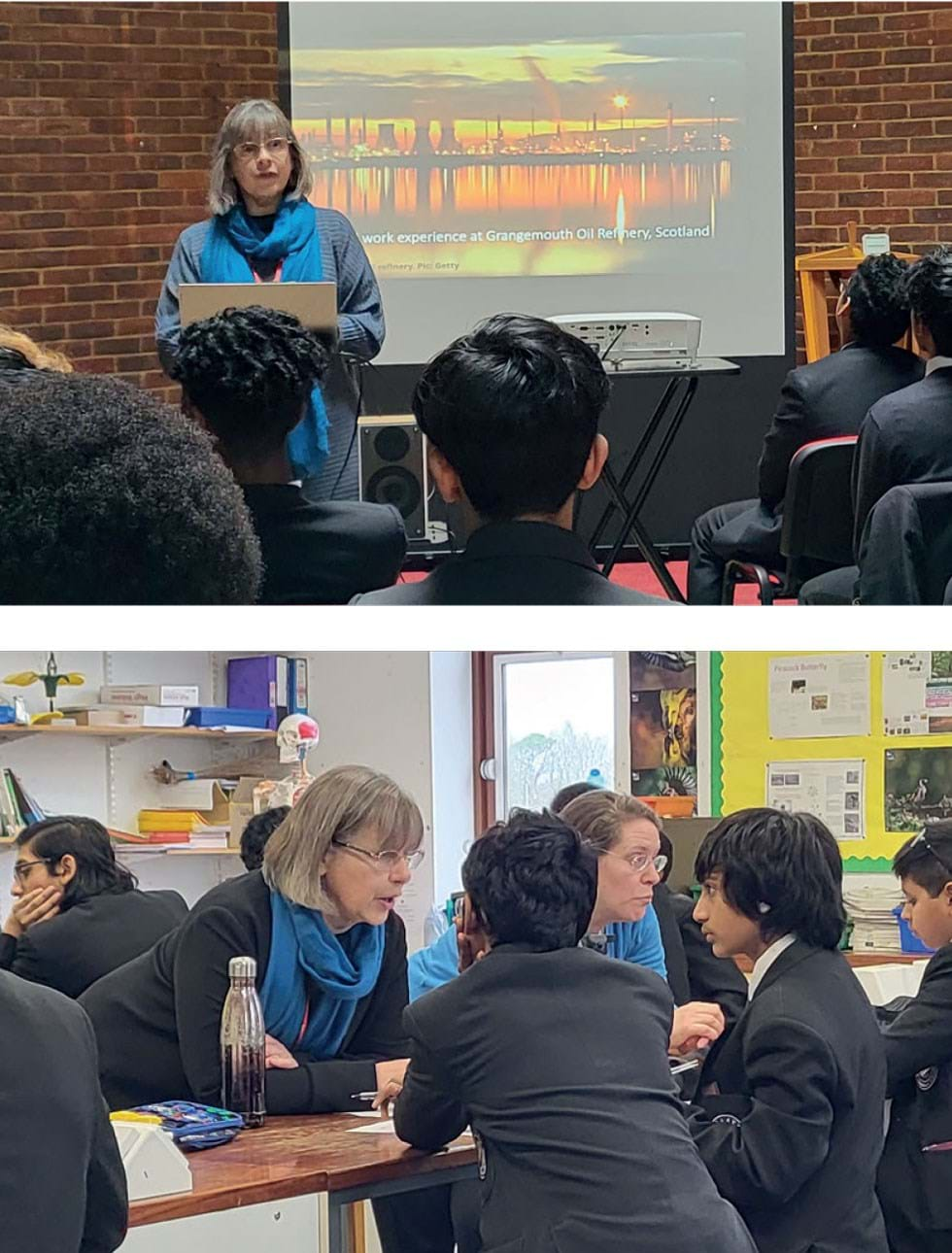

BUBBLING with anticipation, class 8B at St Olave’s Grammar School know they are in for a very different science lesson. Sat in a classic lab classroom, fit with rows of wooden desks and anatomy posters, the group of around 20 boys are poised with exercise books and pens at the ready. Chemical engineer and novelist Fiona Erskine is due any second to give a writing workshop that will test the student’s chemistry knowledge and literary prowess – an unlikely combination.

The task is straightforward enough; the boys have the whole lesson to plan and write the opening of a story about a character’s “great escape” using their scientific knowledge. Fiona provides some inspiration, reading an excerpt from her first book, The Chemical Detective, and discussing the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Twenty minutes of brainstorming and discussion follow before the students frenziedly begin writing their chemical reaction-centred escape plots.

Focusing on STEM

St Olave’s was established in 1571 and consistently ranks among the best grammar schools in the UK. Chock-full of societies dedicated to maths, engineering, and even cryptocurrency, the institution prides itself on its education in STEM subjects.

“We’ve noticed in our school that the students are very STEM focused,” says Joanna Carpenter, a chemistry teacher who has worked at St Olave’s for almost eight years. “They work very hard in their STEM subjects, including chemistry, where many students want to go on to be medics and engineers.” With such a STEM-orientated school, where knowing how to pass exams is a priority, the importance of finding the time to read for pleasure is often undervalued, says Carpenter. “Especially at GCSE English, they don’t seem to have the same appreciation of this being important for their future, and the idea of clear communication being really significant in the workplace.”

Soft skills have become increasingly sought after. According to recent research into the competency of modern business professionals,1 these skills are essential for employees following the introduction of AI into the workplace.

For the STEM sector especially, fluency in communication and collaboration is crucial. This allows technical expertise to be turned into business opportunities as Billy Bardin, a chemical engineer, and the global climate transition director for Dow, explains. Speaking to the American Chemistry Society, he said: “Our scientists must be able to communicate with technical experts as well as with finance, business, commercial, and marketing leaders. The flexibility in communication style and approach is not always easy to develop or master, but when done well, can make a scientist or engineer an extremely influential leader.”

“Our scientists must be able to communicate with technical experts as well as with finance, business, commercial, and marketing leaders. The flexibility in communication style and approach is not always easy to develop or master, but when done well, can make a scientist or engineer an extremely influential leader”

Reading for pleasure

Since 2020, Carpenter has been on a mission to get literature into her students’ hands. “We know the younger people read, the better their communication skills are, the better they do, and the wider their vocabulary,” she says. Forming part of Carpenter’s’s project to promote reading for pleasure, the school has provided reading lists for each taught subject and has lined the corridors with posters featuring recommendations.

Separately, Carpenter says the school wants to promote wider reading in chemistry, helping students move away from learning exam-based text by rote, to a more rounded understanding of how the chemical industry impacts the world. “I want them to be aware of all the work that’s going on to replace non-biodegradable polymers with biodegradable polymers,” she says by way of example.

The project includes suggested reading materials for individual chemistry modules. Among them is Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, a short autobiography chronicling Levi’s experience as a Jewish-Italian industrial chemist working during and after the Second World War under Fascist occupation in Italy.

Another book on the reading list is Phosphate Rocks, Fiona Erskine’s murder mystery novel set in an old chemical plant. It is loosely based on Erskine’s first job in industry, working in a fertiliser factory. Fresh out of university, Erskine remembers the experience as a “baptism of fire”. There she was, “a five-foot-three-and-a-half feminist”, determined to take on the same workload as the hundreds of “rough men” around her.

The novel splices between deciphering murder clues and recounting the history of different minerals and chemical processes. Carpenter loved the book and used the chapter explaining the Haber Process and Le Chatelier’s principle in her classes.

Carpenter then reached out to Erskine who agreed to talk to the students over Zoom about her life as a working chemical engineer. The relationship has progressed to the point where Erskine is visiting St Olave’s for a second time to give career presentations to the school’s older students and writing workshops for the Year 8 science and English classes.

Shadowing Erskine at her morning workshops, it is hard not to be impressed by the exciting, technical escape stories the students conjure up in just 20 minutes. In 8B, the conversations were flowing, the boys using their encyclopaedic knowledge of how different acids can be neutralised as the main plot devices for their stories.

One dynamic escape narrative came from Ahaan, who created a fast-paced and suspenseful scenario involving highly corrosive acid and red cabbage.

“I was interested in how two very corrosive materials and liquids could form a solution that was widely available and non-toxic,” says Ahaan. “Hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide can form salt and water, which I find fascinating. I thought about how I could then incorporate this into a story.”

Running with the idea, Ahaan imagined a scenario where someone was imprisoned with nothing put a cupboard filled with random chemicals, including hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. To facilitate the neutralisation of the acid, Ahaan needed a realistic indicator his protagonist could use.

“I thought that he could use red cabbage which he was given as his rations in the cell,” he explains.

What even is a chemical engineer?

Up at the school chapel, a large room with rows of chairs and crisp acoustics, Erskine is giving a careers talk to the entire Year 10. She recounts her time at Cambridge studying chemical engineering, and how the importance of the profession only really hit her once she got her first job on a graduate training scheme at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI).

The students listen intently as she describes her journey in industry, starting at the bottom as an apprentice, to leading and managing global projects in renewable electricity generation and carbon capture. Her work has taken her to Brazil, India, Portugal, and China, among others, an aspect of the job that opened they eyes of some students.

“I kind of thought that the only thing you could do with chemistry on a major scale was something in the medical sectors,” says one Year 10 student. “I wasn’t aware of the number of opportunities there were to travel the world and meet new people.”

For Erskine, however, travel is more than just a job benefit, it is testament to the wide range of problems chemical engineers can solve together.

She says: “What I like to get across is that it is not as scary as it looks. In school, you’re judged on your own output whereas in real life most of what you do will tend to be a team effort, where people are able to guide you.

“You do not have to be an expert in everything, generally you will have other chemical engineers and other scientists to work with.

“Another thing I try to get across to them is, do not be seduced by the sexy company or product. Google or NASA may look like the best place in the world to work in, but there is actually a whole range of places.”

Becca Gooch, head of research at EngineeringUK, agrees. “It is a broad and interesting sector,” she says. “There are skills needed that are beyond doing the maths. It is important to highlight to people who may not think of themselves as STEM people that there is a place for them in engineering as well.”

The boys and girls at St Olave’s, like many of their peers, are concerned with the grand challenges facing the world such as reducing carbon emissions and building circular economies.

Gooch says it is vital they see a role for themselves in forming part of the solution. “Students see the importance of science and technology to the world, but they don’t always see themselves as being able to do it,” she says.

“Young people are influenced by their local area. If you ask them about the types of things they are interested in related to the environment, kids in the countryside are more likely to say biodiversity, and kids who live in London or another big city are more likely to say air pollution because those are the things that they see.”

Industry talent in short supply

As of 2021 in the UK, there were approximately 6.1 million jobs across all engineering industries, which include civil, environment, and energy. This represents 19% of the whole UK workforce, according to a report published by EngineeringUK2 on future engineering skills.

Despite the large workforce, the report expects engineering occupations to grow by 2.8% by 2030, adding an extra 173,000 new jobs. The range of jobs needed include mining and quarrying, manufacturing, and electric, gas, and air, as well as non-engineering related roles in ICT, administration, and research.

“There is the stereotype of the engineer as the uncommunicative nerd that we need to challenge. But I think when we are criticised, we do hunker down, it’s incumbent on us all to engage with people who distrust the chemical industry or who have very simplistic solutions to the environmental problems that we have”

Reaching out to young students

For many of the students, Erskine is the first chemical engineer they have met, with her talks and workshops providing a rare insight into the inside of a plant and the people who work there.

She says: “It is clear that many teachers do not have a lot of real-life experience. It is thus difficult for them to always guide pupils into what they might want to do.

“There is the stereotype of the engineer as the uncommunicative nerd that we need to challenge. But I think when we are criticised, we do hunker down, it’s incumbent on us all to engage with people who distrust the chemical industry or who have very simplistic solutions to the environmental problems that we have.”

The Year 12 students at St Olave’s face an important year, with prospective university degrees at the forefront of their minds. However, they share similar stories on how difficult it is to secure work experience or resources about working in industry. And while seeing chemical processes in situ are often subject to lengthy preparatory work both in terms of safety and planning, there are less hurdles to overcome when industry professionals visit the classroom.

“I think it’s a case of consistency,” says Gooch. “Even if businesses are only able to do something quite small like talk to a school, if someone else is running a programme with them later that year, it all adds up.

“That sustains engagement among students when trying to support them into a career.”

That support alongside the importance of having role models in the industry is something Erskine is acutely aware of.

During her talks, Erskine recalls her first trip to the Bhopal chemical disaster site and how enraged she was that, after almost three decades, little had been done to fully remediate the site from harmful pollutants.

She had always been passionate about writing and literacy and the experience ignited something in her. She wanted to show the world why and where chemical engineers are needed.

“I do think as engineers and as scientists we must be better at communicating to engineers and non-scientists. I think it’s a two-way street,” says Erskine.

“I hate the arts-science divide, its completely false and damaging. Engineers should read and non-scientists should have an open mind about the most important things that are going on which are going to determine how people are going to live. It is about encouraging people to be more well-rounded.”

References

1. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294906231208166

2. https://bit.ly/3TWH6Lk

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.