Keeping it Local

David Simmonds explains the challenges of pursuing major projects sustainably

Having delivered major projects worldwide for over 40 years, after retirement I volunteered with VSO in Tanzania to help Tanzanians secure sustainable jobs from an expected LNG project. Yes, I had significant experience in managing the many commercial, technical, environmental and safety challenges, but how does one successfully promote local jobs or local content (LC)?

Gaining sponsorship from UKDFID, I saw that traditional approaches to address this challenge were failing, and quickly realised that new strategies were required to get a project to sanction while managing its impact on communities. In the context of project development, LC is generally seen as the ‘tail wagging the dog’, but today new approaches can be drivers to project success. These strategies are needed in an era where governments, civil society organisations (CSOs) and public opinion, fast-tracked through social media, are insisting that investors address all aspects of social impact and sustainability.

This article offers some insights to help deliver today’s projects more successfully for the benefit of all stakeholders. Indeed I am keen for all engineers to look on these to extend their ‘social toolkit’

This article offers some insights to help deliver today’s projects more successfully for the benefit of all stakeholders. Indeed I am keen for all engineers to look on these to extend their ‘social toolkit’. While my examples from projects where I was directly involved, come from major resource developments in Africa, the approach can be scaled to other sectors and regions.

The established ‘social’ toolkit

Over recent years, projects have embraced social impact studies. Typically, these are undertaken as joint environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs)1, and it is imperative that these continue to be undertaken rigorously. However, as far as the social aspect is concerned, their focus has been on the impact during the operational phase.

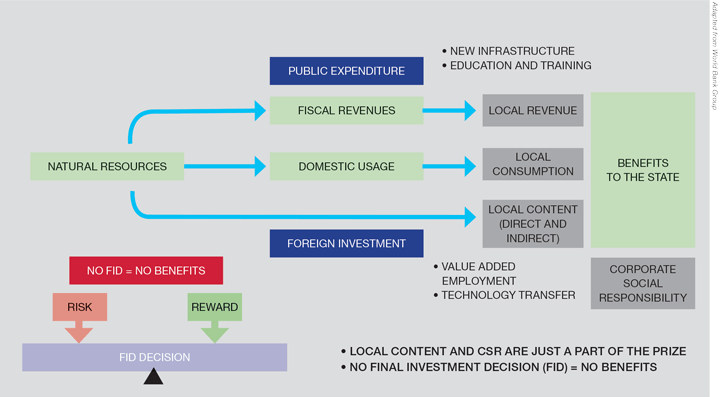

The toolkit for the construction phase essentially comprises what both investors and governments call local content (LC) assessments – ie what can be achieved with local resources (labour, services and goods). Governments insist on these to maximise both local and state benefits, but ultimately fall back on legislation.2 On the other hand investors, working with their contractors, look to minimise cost, maintain schedule to maximise returns, endeavouring to reduce risk by using known and proven resources. Indeed investors often don’t have a real handle on managing LC, often bundling scope into major EPC contracts.

A blanket approach to legislation can drive inefficiencies, promoting non-sustainable goods and services and corrupt practices, especially in regions with limited infrastructure and capacity. There are many examples where it has been difficult to square the circle on these and other stakeholder drivers, and local businesses and communities can become the pawns in the solution. In extreme circumstances, projects may not secure sanction, eliminating potential for any benefit (see Box 13)

Box 1: Olokola LNG (OKLNG) Project Nigeria, 2007

This project between Shell, Chevron, BG and NNPC was planned as an expandable two-train plant, located close to Lagos. Work progressed to the point of an official ground-breaking ceremony, completion of FEED, ESIA and resettlement plan approvals and receipt of bids from two EPC consortia. LC rules in Nigeria were still under evaluation, but minimum standards and expectations were established.

The tenders when opened were 50% over budget, due in no small part to LC uncertainties. Efforts to reduce cost were pursued, but the project failed to secure sanction and remains undeveloped to this day.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.