Time for Change

Grant Wellwood calls for manufacturers to include environmental impact labels on their products

WHILE environmental impact labels won’t save one unit of greenhouse gas (GHG) in their own right (will cost for the ink), they may catalyse the change we all know must happen by creating a level playing field that brings the facts to light in a trusted and high integrity manner. By shining the light of environmental impact on manufactured products at their point of sale we can let consumers make informed decisions about the future they want and drive the change needed to live in a more sustainable manner.

No matter where you sit on the spectrum of the climate change debate, as a chemical engineer you would probably agree that when it comes to the environmental impact of transformational processes, less is more. As the architects and custodians of most processes responsible for incidental industrially-generated environmental impacts, it is right and proper that as a profession we continue to talk about the issue. However, the rate of change seems to be falling short of society’s expectations and there is general agreement that industry’s current trajectory is unsustainable.

In our heart of hearts as chemical engineers, most of us know of process improvement(s) and/or alternate pathways (like those regularly flagged in this magazine) that could reduce environmental impact of our employers’ activities and/or the impact of the goods we consume. Many of us even put improvement projects up as proposals and get demoralised when they fail to get traction. One of the root causes here is that the economic framework within which we operate cannot put a cost on environmental impacts. As succinctly put by the investment bank JP Morgan recently, “climate change reflects a global market failure in the sense that producers and consumers of CO2 emissions do not pay for the climate damage that results.” Our personal frustrations are frequently heightened by the rhetoric and motherhood statements issued by manufacturers and industries in response to the public’s increasingly loud calls for change. Perhaps it’s time for us to step up as a profession and assume the toughest role of all: change leadership?

Innovation generally happens at the speed of trust, not the speed of technology, so perhaps we need to catalyse trust in order to get a reaction? If a catalyst is required, then who better than a chemical engineer?

Pragmatically, all the elements for material change are present – widespread and sustained appetite for change; industry acknowledgement that change is now necessary; and technologies and innovations to materially reduce environmental impact(s) – so why doesn’t it just “go off”?

Innovation generally happens at the speed of trust, not the speed of technology, so perhaps we need to catalyse trust in order to get a reaction? If a catalyst is required, then who better than a chemical engineer?

At a high level the ideal attributes of such a change catalyst might include:

- a way to universally change the global equation in order to ensure prices reflect the true impact of our choices as consumers; and

- a pathway that is both quick to deploy and that cuts across country-of-origin issues and does not rely on legislation.

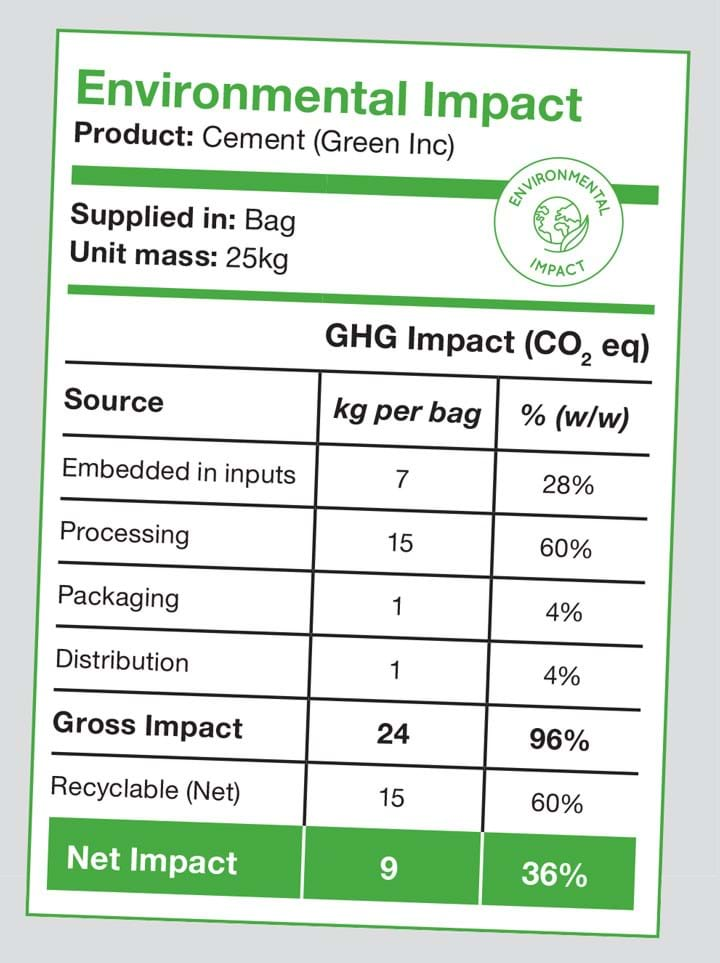

This seems like a tall order, but perhaps there is a way – and could it be as simple as changing the labelling? In this article I propose the development and voluntary adaptation of environmental impact labelling (EIL), in the same manner as food nutrition panels function as a catalyst to giving power to the people at the point of sale in terms of defining the type of future they want.

What would success look like?

In this catalysed world, every product would feature a simple information panel covering the environmental impact of its headline steps to market. For example, it might include the embedded inputs associated with its specific raw materials as well as its processing, packaging and distribution impacts. To help drive the circular economy and give a picture of its life cycle impact, perhaps some information on its inherent recyclability?

Naïve? Perhaps! But why not? It has worked well driving nutritional change in the food sector and it would appear to satisfy the criteria of our ideal catalyst.

Leap-of-faith assumptions

For this simple EIL concept to work, there are three leap-of-faith assumptions:

- It is possible to devise a standard that can generate the credible numbers to populate an EIL and therefore engender trust.

- Factual information about a product’s environmental impact would actually change the behaviour of consumers.

- Manufacturers would respond to changes in consumer buying behaviour.

A CREDIBLE STANDARD?

Is an internationally-agreed standard for formulating EILs possible in the short term? The food industry has managed it, albeit over a number of years, so technically at least it is possible. Time for due process is probably the biggest challenge, but in place of a diverse committee, the IChemE community could stand up something credible quickly as a minimum viable product that could then be refined and expanded. Mass and energy balancing are, after all, core competencies, so there is no profession better qualified to establish conventions and formulate building-blocks and plug-ins.

BEHAVIOUR CHANGE?

Consumer behaviour may be fragmented these days, but it is still a very powerful and empowering force at the end of the supply chain and point-of-purchase is the right place to catalyse. As consumers we feel increasingly frustrated at the rate of change and our inability to influence the situation. Yet every time we purchase a product, we are actually casting a vote for the future we want. Buy cheap low-quality items derived from processes with low or no environmental and high post-production impacts, and we will get more of the same in the future, and vice versa. Through this lens, consumers actually have immense power to drive change, so what’s missing? Factual information!

When products are presented as commodities, all we really have to cast our vote on is brand reputation and price. Prices are not reflective environment impacts, distorted by government subsidies, monopolies, supply chain quirks, tariffs, and cross pricing. If the market alone can’t present an accurate, informed price picture upon which we can cast our votes for the future, perhaps engineering can assist?

If we were able to see the whole-of-life environmental impact of each product, would this influence our purchasing behaviour-vote? It has certainly worked well for food, helping consumers make informed choices and driving the industry to change. Think about the changes in relation to fat, salt, sugar contents, unthinkable just ten years ago. Every time I am faced with a food choice, I read the labels and make an informed choice. I am also prepared to pay a premium for options that best align with my values, recognising the higher costs involved in bringing them to me. I do this for my future health, and I would certainly do it for environmental future as well. Healthy foods continue to expend their market share despite their premium pricing and many people in my network feel the same. As an aside, you could put the same question to people in your network to gauge the sentiment.

INDUSTRY CHANGE?

Manufacturers routinely sweat over daily sales volumes so even small changes in this metric are guaranteed to drive change. There are many examples where changes in consumer sentiment have led to swift and material manufacturing change:

- removal of Bisphenol A (BPA-Free) from the manufacture of plastic food containers;

- reformulation to remove palm oil;

- reformulation to reduce sugar, salt, saturated fats levels;

- reformulation to remove lead from petrol; and

- development of functional foods.

If we accept that change in response to strong and sustained consumer demand is a given, the issue of EIL collapses to one of voluntary industry adaptation, and this is where chemical engineers can also catalyse the change agenda.

Manufacturer adaptation; push or pull?

Attempts to alter the financial framework to better reflect the overall cost (financial and environments) through government legislation (carbon tax) faulter, and we collectively stare in wonder at the inadequacy of industry self-governance. Previous attempts at implementing environmental impact labelling have focussed on retailers to drive the change, but I think manufacturers are the right focus.

Let’s be honest, most of us know dirty little secrets about our own industry in terms of environmental impact(s) (yield, inefficiencies, additives, rework...) that would be a surprise to consumers if the facts came to light. So what would drive EILs that would out these impacts? In short, it would be a slow process to push manufacturers to change. Enter the catalyst.

In an environment of heightened public appetite for change and transparency, “pull” is a better strategy for change than “push”, and the catalyst could be as simple as a few early adopters, organisations that are prepared to walk the talk of change. Until there are comparisons, first movers could be at a disadvantage but this is where IChemE could help. For example, adding a separate column with “typical” industry values to enable labelled products to be compared and contrasted with peers could effectively kickstart the process. Consumer power would then force laggards to follow suit lest they be judged as having something environmentally sinister to hide. If this happened, the process would have been catalysed into action and would then proceed to completion on its own.

If you are still with me at this point, you will appreciate there are more questions than answers, but hopefully you see some merit. Leading such change will not be easy, but it is the hallmark of our profession and it’s time to stand up once again.

What role can IChemE play?

Integrity, trust and deep subject and process understanding are the keys to successfully leading this change process. As the widely respected body representing professionals in this subject matter area, IChemE can leverage and indeed build on its community standing by leading this change effort.

Specifically, we could bring our experience to bear to propose a science-informed and transparent framework to devise a template and generate EILs. Presumably this would involve establishing sensible definitions for building blocks (embedded impacts, processes, packaging and distribution, transportation) that could then be put together in any combination to get specific EIL. Once the framework was formulated, perhaps longer-term, and with resources permitting, IChemE could then train practitioners and auditors globally? We could even consider IChemE certification to accompany EILs, as a way of establishing quality, the income from which could be used to fund our involvement?

All this involvement doesn’t involve preaching, compulsion, or governments – it’s all about applying our science to shine light on environmental impacts, a good fit with our charter and profile as do-ers and natural leaders, not just talkers. What other profession is better placed to take the lead?

Next steps

Before you post it, I am aware of the irony that this article is yet more talk. So what would be required to start catalysing the reaction? For manufacturers of lower-impact alternatives, there is no easy way for them to differentiate themselves from their competitors in the market apart from slapping the word “Green” on the packaging. Something like an EIL would change all that, and if they were successful in winning market share competitors would be forced (“pulled”) to follow or otherwise be judged as having something to hide. If you work for such an organisation you could raise this idea straight away.

Our special interest groups in this area (eg the Sustainability SIG and the Environment SIG) could help you put forward something in the manner of a lean startup process to start the learning. In addition to increased sales there is a lot of kudos and prestige in organisations that move from talking to doing. Everyone remembers the first movers better than the “me-too” fast followers.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.