Home Hydrogen: Is it Safe?

Tom Baxter looks at the evidence

FOR households considering a future prospect of hydrogen energy for their homes, there are two questions that I think would be top of the list: how much does it cost? And is it safe? I’ve discussed cost in previous features, so will now look at safety.

Hydrogen is inherently less safe than natural gas, from a fire and explosion standpoint. It has a much broader explosive range, it is much more prone to leaking, a much lower ignition energy level, and can produce higher over-pressures on explosion. In its favour though is its buoyancy; it will disperse more easily and there is no carbon monoxide emission risk with hydrogen combustion, but that does not affect fire and explosion risk. Another downside to hydrogen is it produces more NOx than natural gas when combusted.

Quantified risk assessment

The UK Government investigated the safety of hydrogen during Work Package 7 of the Hy4Heat programme. The aim was to demonstrate that hydrogen for household heat can be made as safe as natural gas, from a fire and safety viewpoint.

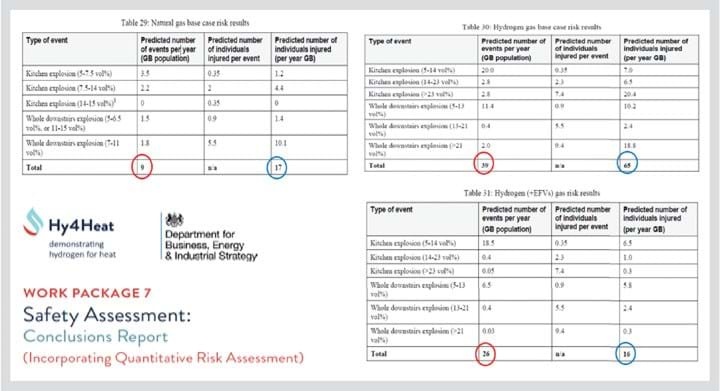

To demonstrate comparable risk, Hy4Heat conducted a quantified risk assessment (QRA). This was undertaken by Arup, and summarised results are shown in Figure 1. Recall some basics – risk is a combination of probability of the event happening and the consequence of the event.

Comparing natural gas base case (Table 29 in Figure 1) with the hydrogen base case (Table 30), it is clear that there will be many more fire and explosion events with hydrogen – 39 per year compared with 9 for natural gas.

Coupling that with the event consequence gives an overall risk of injury of 65 for hydrogen compared to 17 for natural gas. Clearly, unmoderated hydrogen for domestic heating is much less safe from a fire and explosion standpoint than natural gas and does not meet the Government’s aim of similar risk.

To bring the overall risk down to the same level as natural gas, Arup has recommended installing two excess flow valves (EFVs) in series (Table 31 in Figure 1) for future hydrogen boiler installations. If a hydrogen leak occurs in a household, the EFVs are there to reduce the size of the leak so the consequence of a fire and/or explosion will be reduced.

Table 31 shows that, because of the reduced consequence, the overall risk is now the same – 16 compared to 17 injuries. However, the frequency of fires/explosions remains three times higher for hydrogen than of natural gas – 26 compared to 9.

The way I read the EFV-moderated analysis is that there will be three times as many fires and explosions with hydrogen but, because the EFVs have reduced the size of the hydrogen gas leak, an individual is less likely to suffer injury.

The Hy4Heat QRA project concludes: “This assessment indicates that the use of 100% hydrogen can be made as safe as natural gas is when used for heating and cooking in certain types of houses (detached, semi-detached and terraced houses of standard construction), that were studied.”

But is it that safe?

I have worked with hazardous substances for more than 40 years and taught process safety. To my mind, the Arup QRA is not a convincing demonstration of the domestic safety of hydrogen. Would you buy a car if the salesperson told you it would crash more often, but because of the safety features you’d be just as safe?

Here is another take. The risk to an individual is made up from occupancy in two locations: the kitchen and the entire downstairs area. If you look only at the kitchen (a place where I spend much of my time) the probability of an EFV-protected hydrogen explosion is 19 compared to 6 for natural gas. The overall risk is 8 injuries for hydrogen and 6 for natural gas. The kitchen is now a less safe place.

Let’s extend that argument to two adjacent chemical plants – A and B. Modifications are made that mean the individual risk in plant A increases but reduces in plant B. I work in plant A; do I accept my increased risk is acceptable because other colleagues are safer?

The Royal Academy of Engineering’s (RAEng) recent report cites Hy4Heat, and commentated that: “Nevertheless, there are limitations of the Hy4Heat assessment that future projects and demonstrations will need to address, such as flats and multi-occupancy buildings, housing that lacks natural ventilation, and the safety of supply through gas networks to homes. The Health and Safety Executive independently reviewed the evidence and was satisfied that the assessment provides an adequate basis for gas network operators to design and risk assess future hydrogen trials.”

The Health and Safety Executive independently reviewed the evidence and was satisfied that the assessment provides an adequate basis for gas network operators to design and risk assess future hydrogen trials

The RAEng is referring to a letter of assistance that the HSE sent to BEIS that states: “With reference to the attached Annex containing health and safety evidence obtained and/or established through the Hy4Heat programme, HSE is satisfied that this provides an adequate basis, if applied appropriately by the relevant dutyholder, for: Designing the scope of future hydrogen trials; Assessment of the risks arising from those trials; and Management of those risks in accordance with a suitable and sufficient risk assessment for those trials.”

Clearly the RAEng has not declared a position on domestic hydrogen safety. Its report merely echoes the HSE statements.

The HSE is not saying that household hydrogen has been demonstrated to be safe. The letter of assistance only provides authority for further work to be conducted using limited domestic trials.

Conclusion

Whilst the BEIS has stated that it will wait until 2026 before making a decision, I am unequivocal – there is sufficient knowledge and evidence available now to dismiss hydrogen for domestic heat.

I have seen very few third-party critiques of the Hy4Heat QRA and conclusions reached. I’d dearly like to know what the IChemE technical safety community thinks, as I believe IChemE has a major contribution to make in the hugely important net zero domestic heat debate.

As a closing thought, I was fortunate enough to meet and attend Trevor Kletz’ training courses when I worked for ICI Petrochemicals. Kletz made a huge contribution to process safety, and I use much of his teachings in my own safety lectures. He structured inherent safety as:

- Intensification: Use small amounts of hazardous materials so the consequences of accidents arising from the escape of materials are much reduced.

- Substitution: Use a less hazardous material – less flammable or less toxic.

- Attenuation: If a hazardous material must be used, use it a) under less hazardous conditions or b) in the least hazardous form.

- Limitation of effects: Limit the effects of failures by changing the design or conditions of use rather than by adding protective equipment that may fail or be neglected.

Domestic hydrogen does not sit well with the above inherent safety principles. I wonder what Kletz would have thought about household hydrogen using excess flow valves to mitigate the risk of fire and explosion?

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.