Dreaming Big and Changing the World Through Chemical Engineering

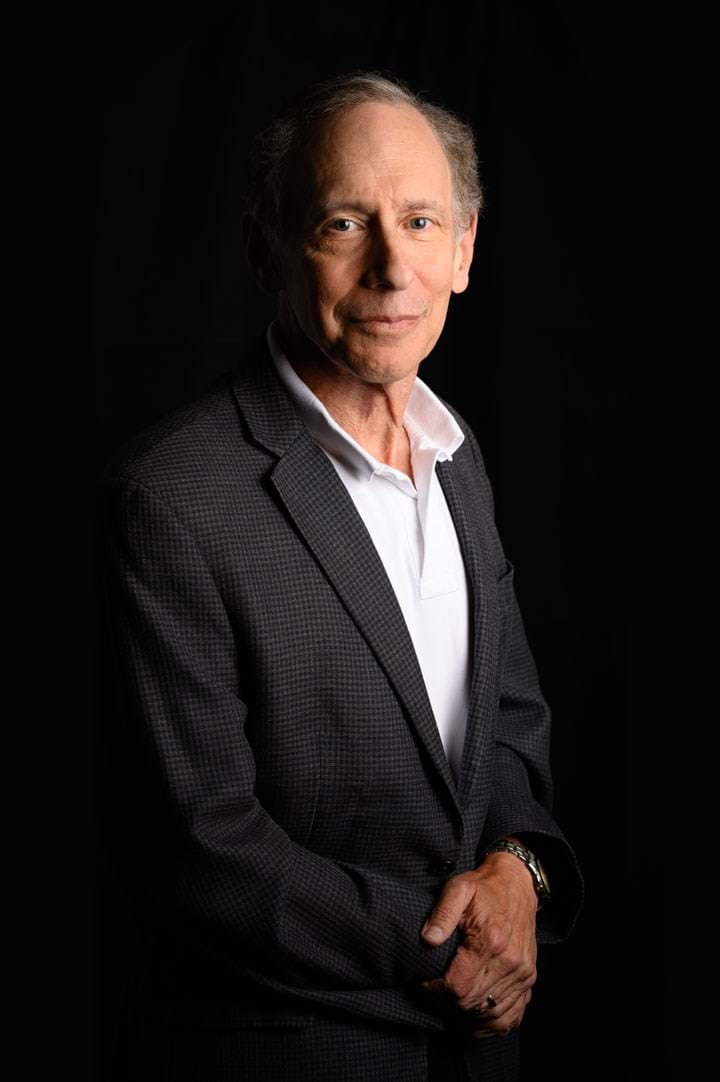

Amanda Jasi speaks to pioneering chemical engineer Robert Langer about his successes and offers advice for the next generation of chemical engineers looking to change the world

CHEMICAL engineer Robert Langer is the most cited engineer in history, and his achievements include the 2015 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering, awarded for his revolutionary advances and leadership in engineering at the interface with chemistry and medicine. He is a co-founder of biotechnology company Moderna, one of the first companies to develop mRNA vaccines, which helped to tackle Covid-19.

He graduated from Cornell University with a Bachelor’s in chemical engineering, and later with a doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He has worked at MIT since, where he is now the David H Koch Institute Professor, and leads the Langer Laboratory, which operates at the interface of biotechnology and materials science.

Why did you pursue chemical engineering, and what continues to motivate you?

“In terms of getting to be a chemical engineer, I wanted to do something useful for the world and I think chemical engineering has given me great training to do that. Chemical engineers have a good background in chemistry and engineers solve problems, and I’ve really enjoyed trying to solve problems that I hoped could make a big difference in people’s lives and in people’s health. And I feel very lucky that I’ve been at MIT because I’ve had wonderful students, and though one person can get an award, many people really are responsible for it.

“In terms of what drives me now, now I’m 73, if I want to retire, I guess I’m old enough to do that. But I love what I’m doing, I love working with the students, I love seeing the things we do, hopefully, make an impact on the world. And I have a lot of ideas that I want to pursue and try to see if we can make new kinds of vaccines, new kinds of therapeutics, better nutrition. And I want to train the very best chemical and biomedical engineers for the future.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has seen a rapid response in terms of drug development. What are the important lessons to learn for future developments?

“I think there’s a couple. One concerns messenger RNA therapeutics – that’s something I’ve been very involved in – and the nanoparticles to deliver them. I think these will change the future. I think it will be a whole new way of creating both vaccines and therapeutics, and you can do so so much more rapidly than you could ever do before. At Moderna the scientists there were able to design the vaccine in less than two days. That’s really pretty unprecedented.

“There are other lessons too. I think that things like Operation Warp Speed and the way that regulatory agencies responded really showed that if people feel there’s an emergency, you can do things faster, and I think that was also a very important lesson.”

Are any technologies in the pipeline that could be as breakthrough as the mRNA platform?

“In the biotechnology area, there’s a lot of things going on with cellular therapies, both in regenerative medicine and chimeric antigen receptor T-cells. In the vaccine area, there’s a lot of technological developments that are going on, which we’ve also been involved in: new kinds of nanoparticles; new ways of creating what are called self-boosting vaccines, that you could inject once, but could be a cocktail of vaccines that could pulse at different times in the body so that you would never need to come back for a second injection; micro-needle patches that you could ship all over the world, they’re like little band-aids that people could put on. I think there’s a lot of technological developments that can make vaccines better and better.”

What is needed to allow these technologies to have an impact?

“I think funding is the number one thing. Regulatory authorities moving more quickly is another.

“The way I look at it is there’s two ultimate sources of funding. In general, one is investors. I think that if investors didn’t put in literally billions of dollars into Moderna, and BioNTech, for a good ten years before Covid, those two companies would never have been in a position to make the RNA vaccines.

“At Moderna, we had nine vaccines in clinical trials by the time Covid came about. We also had a manufacturing facility, and we had done a lot of work on the nanoparticles, and a lot of work on the RNA. Almost all of that money came from investors. And there are laws that could make it either more attractive for investors or less attractive for investors to want to come in to help create a Moderna or a BioNTech.

“The government can also be a major source of funding. The US Government put in, through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority and Operation Warp Speed, billions of dollars.”

What advice would you give to someone who is a chemical engineering undergraduate or a recent graduate looking to enter your field?

“I give this advice when I give commencement speeches. I tell people to dream big dreams that can change the world and make it a better place. I also say that if you do that, you may run into a lot of obstacles and people telling you that your ideas won’t work. And I tell them, don’t give up easily, keep trying.

“I had a mentor, Judah Folkman, who had some ideas about treating cancer and other diseases and a lot of people told him he was wrong, it would never work. But it ended up working, and I felt lucky to have known him and to participate in that work with him, which led to the creation of a lot of new anti-cancer drugs. Actually, even the basic work I did on that helped lead to the nanoparticles that would create these Covid vaccines.”

What would you say has been the key ingredient to your success?

“For me, what was unique about my career was that I was a chemical engineer and then I worked in a hospital, and I was actually the only engineer that worked in the hospital. Knowing chemical engineering on the one hand and learning medicine on the other, I think gave me all kinds of ideas that I wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. I just thought differently about medicine, being an engineer, than the people at the hospital who were biologists.

“But, I also paid a price for it. When I started looking for chemical engineering jobs after I finished the work at the hospital, no chemical engineering department would hire me. They all felt that this bio stuff I was doing wasn’t engineering. But that’s changed now.

“Now a lot of chemical engineering departments have bio in their name, there’s a lot more bio-engineering departments than there were. It’s a lot better now and it’s allowed chemical engineers to have more of an impact in different areas, areas that they might not have had an impact on previously.

“In every challenge, whether it’s nutrition, or energy, or medicine, chemical engineers are playing a really significant role, whether it’s basic work in universities, to companies which commercialise and create products.

“I think engineering is a wonderful profession. I feel very privileged to have learned chemical engineering, which I think has been important for years, and will continue to be important.”

Frances Arnold and Robert Langer spoke to The Chemical Engineer as part of a campaign for the Engineering Heroes film series, launched by the Royal Academy of Engineering in partnership with Amazon and Becoming X: https://www.thisisengineering.org.uk/latest/heroes

Read the Frances Arnold interview here

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.