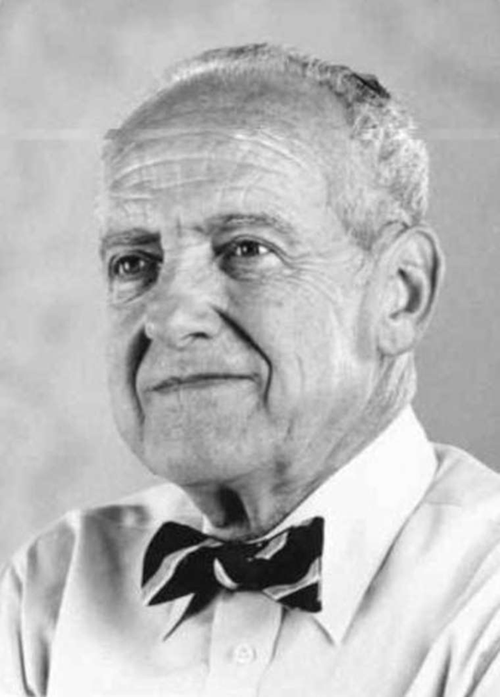

Nathaniel Wyeth – Got a lot of bottle

Richard Jansen-Parkes looks into the life and times of Nathaniel Wyeth, inventor of the PET bottle

NATHANIEL WYETH was in many ways the odd-one out in his family, but not in the way that one might expect. Far from the common narrative of a lone artist looking to break free of a life in the family shop or down the mines, he was a born engineer raised in a house dominated by the arts.

His father was the famed illustrator NC Wyeth, who encouraged all of his children to freely express themselves and expand the powers of their imagination. While Nathaniel’s brother Andrew and sister Henrietta both took to the paints and pencils, both becoming successful artists in their own right, he instead showed his creative talents by taking apart clocks and rebuilding their mechanisms into engines for toy speedboats.

Far from disapproving of his son’s preference for the practical side of things, Wyeth’s father declared that “an engineer is just as much an artist as a painter.” He encouraged him to make use of his talents, going so far as to change his name from Newell – after NC himself – to Nathaniel, after an uncle with a successful career in engineering.

Speaking to a reporter many years later, Wyeth insisted that his father had never been disappointed with his choices in life.

“The only thing he insisted on was that whatever we did, we should do it with all our hearts, with all our might,” he said.

In a bid to help him along with achieving that, his father drafted in another uncle to identify the best technical colleges in the country, and Wyeth eventually followed his recommendation to study engineering at the University of Pennsylvania.

A career engineer

After graduating with both a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree he joined Delco, an auto-parts company based in Ohio, recommended by his namesake uncle. There, he made a good impression early on by solving a production problem in the manufacture of cleaning product Sani-Flush.

One of the ingredients kept plugging a valve in a machine that mixed the cleaner. The valve crossed from one side of a pipe to the other, but sometimes couldn’t close entirely because the gritty, acidic material was in the way. Seeing a solution, Wyeth replaced the single-gate valve with a two-door version. The two doors met in the middle of the pipe where the material was moving fastest and less likely to clog.

That innovation convinced Wyeth’s superiors at Delco of his worth, and earned the young man a promotion to the company’s R&D lab.

Though he enjoyed the work, Wyeth soon made the move to chemicals giant DuPont, which operated its labs near his Pennsylvania homelands. He took up his first role with the company as a field engineer in 1936 and would spend the rest of his career working his way through its ranks.

He later worked as an assistant laboratory director and was named DuPont’s first engineering fellow in 1963. A dozen years later he became the company’s first senior engineering fellow, its very highest technical position. In 1976 he retired and went to work as a consultant with DuPont’s college relations section.

In all the time he worked for DuPont, Wyeth was constantly inventing and innovating. His first invention was a machine that automatically filled cartridges with dynamite. Previously, the process involved a lot of manual labour, requiring that employees be exposed to nitroglycerin, which isn’t just highly explosive, but also dilates blood vessels and creates painful headaches. DuPont wanted to minimise this exposure, so Wyeth built a machine that did it all automatically.

He created a prototype that impressed his boss, who in turn showed it to the explosives supervisor, who showed it to management. Quickly, the company ordered that a final version of the machine be put into production.

“That was music to my ears,” said Wyeth. “To see an idea finally go into motion is one of the most gratifying experiences I think anyone can have.”

Though he has a long list of successful innovations, Wyeth’s biggest and most memorable achievement came when he took up the task of developing a new type of drinks bottle

Revolutionising the bottle

Though he has a long list of successful innovations, Wyeth’s biggest and most memorable achievement came when he took up the task of developing a new type of drinks bottle. Despite the roaring success of Coca-Cola and other sodas, at the time all carbonated drinks had to be sold in heavy, fragile and expensive glass bottles.

Though plastic was becoming increasingly widespread, when Wyeth first worked on the problem in the late 1960s, nobody could work out a way to make it store carbonated drinks safely. He reportedly tested the problem at home by himself, filling an empty detergent bottle with ginger ale and leaving it in the fridge overnight. When he returned the next morning the bottle had swollen so much that he couldn’t get it out, having to pierce it to bleed off the pressure.

Adopting a stretching technique he had used to strengthen nylon fibres in previous projects, Wyeth started experimenting with cold-stretching plastic molecules. From his experience working with nylon, Wyeth knew that the strength of plastic increases when it is stretched. When making nylon thread, for instance, stretching causes the molecules in the material to line up. But unlike thread, which needs to be strong in only one direction, plastic bottles needed to be strong in every direction at the same time.

So he devised a way to extrude the plastic with crisscrossed flow lines, which reinforced themselves and created a uniformly strong bottle. The plastic he was using, however, was not self-balancing – it kept stretching in one direction until it burst.

He switched to polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, which stretched in one place when the limit was reached somewhere else.

Working with one assistant and a hand press, Wyeth said that he produced many ugly, shapeless globs of plastic.

“I remember bringing some of those samples over to my boss,” he told an interviewer. “He’d ask, ‘Is this all you’ve done for US$50,000?’”

Wyeth estimated that he had made around 10,000 attempts at creating the PET bottle. Countless attempts were thrown away because they were not strong enough or were simply miscoloured or prone to warping and bending strangely.

When success came, he and his assistant opened the mould expecting more shapeless globs of resin. Instead, the mould seemed to be empty. They looked closer, and found a crystal-clear bottle.

“Since then, I’ve seen countless truly beautiful PET bottles,” said Wyeth. “But none of them will ever be as memorable as the first.”

Beautifully clear, incredibly light and unbelievably strong, PET was the ultimate material for replacing glass in bottles. DuPont began its first tentative production of the material in 1973 and by the end of the decade it was producing more than 2.5bn bottles per year.

Creativity

These days the majority of the world’s PET production is for synthetic fibres, with bottle production accounting for about 30% of global demand. Even so, a massive amount of Wyeth’s bottles are still being used to this day, with more than 2m t of them being collected for recycling alone in 2011.

The plastic bottle is a truly ubiquitous product, found in shops, homes and backpacks in every single corner of the globe. Though issues remain over the biodegradability – Wyeth’s bottles are so tough they will last for millions of years if not recycled – they are re-sealable, reusable and an incredibly light and efficient way to transport water.

Even beyond the bottle, over the course of his career, Wyeth invented or was the co-inventor of 25 products and processes in plastics, textile fibres, electronics and mechanical systems. A chemical engineer to the core, most of his inventions were processes that accomplished things more rapidly, more efficiently or less expensively.

Though he declared that he was never jealous of his artistic relatives, Wyeth frequently referred to himself as “the other Wyeth.’’ Although widely known in his own field, he likened his fame to oblivion when measured against that of his artist relatives.

“It bothered me for a while,’’ he once told an interviewer. “But then I figured they needed the publicity more than I did to help them move their wares. I’m in the same field as the artists – creativity – but theirs is a glamour one.’’

Originally published in August 2015

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.