Magnus von Braun – Rocket man

Overshadowed by his brother Wernher, Magnus von Braun still had a fateful role to play. Claudia Flavell-While recounts the story

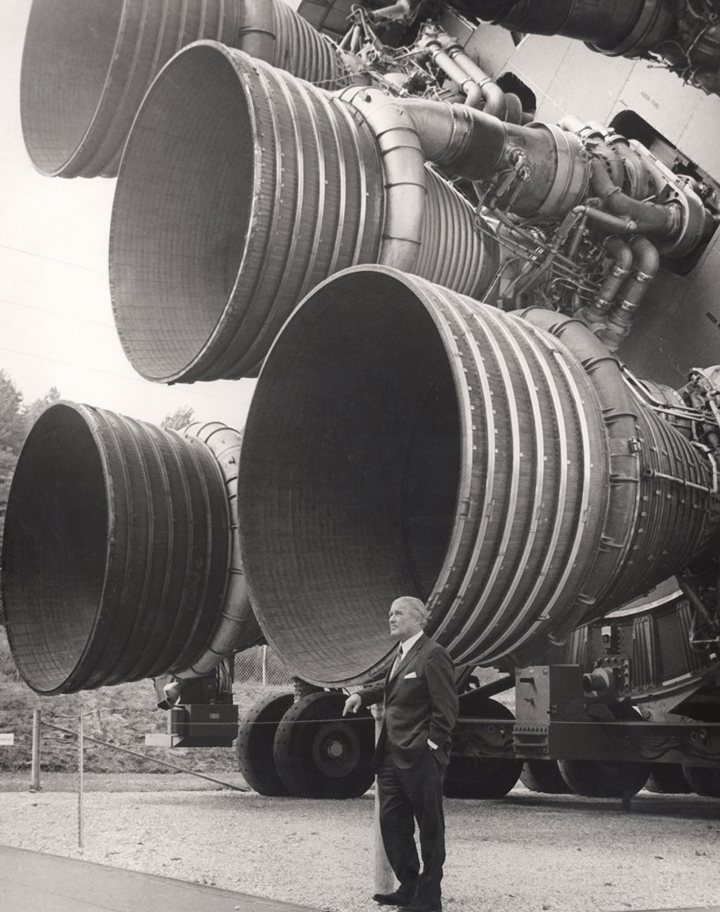

EVERYONE knows about the V-2 rocket programme – Hitler’s project to develop a long-range missile which laid the foundation for the space age, rockets, ICBMs and everything in between. Most people also know about Wernher von Braun, the charismatic German engineer who led the programme and who, after the end of the war, moved to the US where he was to lead the development of the Saturn rockets that eventually would put a man on the moon. But what about Wernher’s younger brother, Magnus?

Magnus – not to be confused with the von Braun brothers’ father, Freiherr Magnus von Braun – was a chemist and engineer who for a time also worked on the V-2 programme alongside Wernher. His technical achievements have always been overshadowed by those of his brother, though he did play a role. But his biggest contribution, and one that undoubtedly did change the world, was no invention or engineering insight. It was he who, when it was clear that Germany would lose the war, ensured that the V-2 programme fell into the hands of the Americans rather than the Russians.

Privileged beginnings

Magnus von Braun was born in 1919 in Greifswald, Germany. His father, a politician and minor noble, had a variety of roles in the civil service culminating in a brief spell as agriculture minister in the Weimar Republic – a post from which he was dismissed when Hitler came to power in 1933. His mother, also a member of the German aristocracy, encouraged her sons to take an interest in science: Wernher’s present on his confirmation was a telescope.

In 1937, Magnus moved to Munich to study organic chemistry at Technische Universität München, where he stayed on for a few months after graduating to work with the Nobel laureate Hans Fischer. In October 1940, he was drafted into the German Luftwaffe (air force), completed his training and eventually became a flight instructor. From there, he was assigned to developing fuels for the Wasserfall surface-to-air missile project until, in October 1943, his brother requested he join him at Peenemünde on the Baltic Sea coast to work as his technical assistant on the V-2 programme.

Mittelwerk and the V-2

The following year he agreed to oversee the production of gyroscopes, servomotors and turbopumps for the V-2 at Mittelwerk, which were experiencing technical difficulties due to some sub-standard components. Mittelwerk was an underground factory at Nordhausen, Thuringia that produced a range of weapons for the Nazi regime. The work was carried out by forced labour from the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp. An estimated 20,000 labourers died at Mittelwerk, most from overwork and malnutrition. This far outstrips the 7,250 soldiers and civilians who died in V-2 rocket attacks.

Magnus von Braun was present in September 1944 when the team learned, through newspaper reports, that the V-2s were being fired on London. The mood was grim – the tide in the war had turned and the engineers had severe doubts that their rockets could live up to the hype and be the ‘wonder-weapon’ the German propaganda machine was making them out to be.

Dieter Huzel, who had replaced Magnus as Wernher’s assistant, wrote in his book Von Peenemünde nach Canaveral: “Propaganda tends to be ahead of the facts, but it is important that those spreading it know the reality. We severely doubted this was the case. We feared that Goebbels and his friends had started to believe their own propaganda.”

Wernher von Braun’s assessment was sober. According to Hutzel, he told the team: “We must not forget that this is only the beginning of a new age, the age of rocket flight. The sad truth, as you can see for yourselves, is that new inventions are of no interest to anyone until someone devises a way to use them as weapons.”

Fleeing south

By early 1945, the Allies were closing in from several fronts and it was clear that Germany was losing the war. At the end of January, key war projects including the V-2s were ordered to move inland to central Germany. The V-2 team was initially relocated to Bleicherode, near Nordhausen and the Mittelwerk. But any plans to carry on working there were short-lived. Within weeks or arriving at Bleicherode, Allied tanks were moving into the area and the team decided to flee. This time, it would be without its work. They would not waste effort moving technical equipment, though Wernher decreed that before they left, they should hide the top secret files detailing the rocket research. According to Huzel, he said: “We’ll hide them somewhere in the mountains, until they’re needed again” – prompting Huzel to write: “Who would be the ones to seize the priceless results of our research – the Russians or the Americans? The decisions we had to make now would influence who would catch us first. At least we still had something akin to a choice in this.”

The paperwork alone amounted to several lorry-loads of files. Eventually, after considerable searching, the V-2 team found a suitable hiding place in an abandoned mine shaft. After that, the von Brauns and their people headed on. The decision was to move further towards the west, and with that, towards the American lines.

The journey eventually took them to Oberammergau in Bavaria, at the foot of the Alps – dodging not just Allied bombers and fighters, but also hazardous roads packed with refugees. The car Wernher was travelling in promptly got caught up in a collision, resulting in the broken arm that is prominently visible in the photos.

By the time the team reached Oberammergau, the place was, in the words of Huzel, crawling with German SS officers. Wernher was deeply suspicious of their motives (“They might pursue a scorched earth policy and destroy us along with everything we’ve worked for”). Accordingly, the V-2 team decamped to the tiny hamlet of Oberjoch, which they felt was remote enough and reasonably defensible. They arrived on 15 April 1945.

Wernher would eventually become director of the Marshall Space Flight Centre in Huntsville, Alabama, and take the Americans to the moon, while Magnus began a career in industry

A fateful bike ride

Two weeks later, on 1 May, the news broke that Hitler had “fallen in combat”, as it was reported at the time. Huzel recounts how the following day, Wernher convened the key members of his team. “He seemed more relaxed than he had in a long time. He told us, simply but empathically: ‘Magnus, who speaks English, has just ridden away on the bicycle to make contact with the American troops at Reutte. We can’t stay here waiting forever.’ “

Another member of the V-2 team, Ernst Stuhlinger, later said: “It was quite courageous for Magnus to come down on his bicycle and find the American troops. He had a white handkerchief tied to the handlebars of the bicycle and that was all he had to protect him.”

The first American Magnus encountered was a young private called Fred Schneikert. A German speaker, he yelled: “Halt! Komme vorwarts mit die Hände hoch!” (Stop! Come forwards and keep your hands up). Magnus replied, in broken English: “My name is Magnus von Braun. My brother invented the V-2. We want to surrender.” Schneikert reportedly told Magnus “I think you’re nuts,” but he did get his superiors to investigate. Fortunately, they were more inclined to believe the story, and in the afternoon Magnus returned to tell everyone that he had made all the arrangements with the Americans.

The following day, on 2 May 1945, the von Brauns and their inner circle were on their way to the American camp at Reutte to be debriefed.

After the war

Six months later, the von Braun brothers were on their way to the US, aboard the SS Argentina, along with several other key members of the V-2 team. Most of the rest also moved – some 120 former V-2 men took up residency in a former hospital at Fort Bliss and shared their knowledge with the Americans, along with the technical documents and blueprints which had, by then, been retrieved from the former mineshaft. Wernher would eventually become director of the Marshall Space Flight Centre in Huntsville, Alabama, and take the Americans to the moon, while Magnus began a career in industry. He worked with Chrysler, first in the company’s missile division and later in cars. That role took him to the UK for a number of years where, as Chrysler’s UK export director, he was based in London and Coventry. Following his retirement in 1975, he returned to the US, where he died in 2003.

Originally published in December 2012

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.