Lewis Urry – A Powerful Man

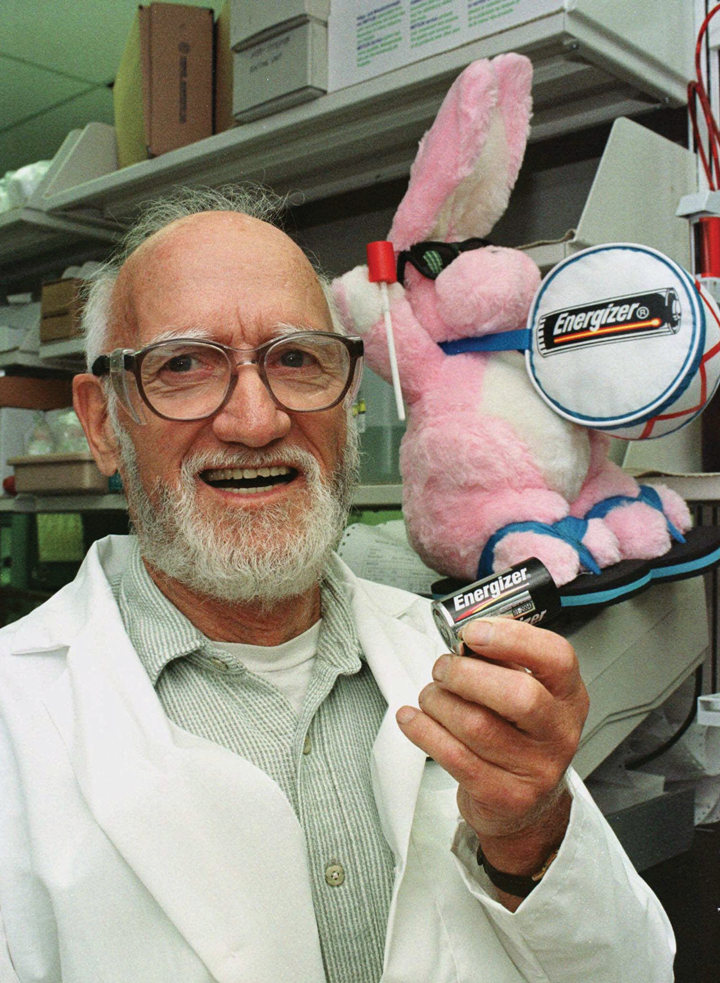

Richard Jansen-Parkes looks at the life of Lewis Urry, inventor of the alkaline battery and father to the Energizer Bunny

IT IS perhaps the sign of a good invention that you don’t think about it at all until it’s suddenly unavailable. This is certainly true in the case of the long-life alkaline battery – as a great many disappointing Christmas mornings can attest.

The man who created it is rarely recognised for his work. For while very few people have ever heard of Lewis Urry, without him the world would be rather different – and certainly much less portable

Building better batteries

Born in a small town in Ontario, Canada in 1927, the most surprising part of Urry’s formative years is how normal they were. He spent three years in the Canadian military, joining just after the end of World War II, and stayed within his home province to study chemical engineering at the University of Toronto.

It didn’t take long, however, for him to start making a name for himself. Hired straight out of university by Eveready, Urry had been working at the company for just five years when he was commissioned to create a longer-lasting battery.

Eveready had been making batteries since the late 1800s, but by the mid-50s very little had changed in its designs and the industry was struggling to match power demands.

“In those days, toys were coming out that ran on batteries, but they didn’t sell well because the carbon batteries on the market died after a few minutes’ use,” Urry told the Washington Times in 1999.

In order to make this new battery Urry was moved from his base in Toronto to a laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio, where he was supposed to work on increasing the life of the company’s standard zinc carbon battery.

While he was researching the possible methods of increasing the zinc carbon battery lifespan, however, he realised it would be much more efficient and more cost effective to create a whole new type of battery from scratch.

Scientists had long been experimenting with cells that used an alkaline electrolyte, which generates more power, but no-one had been able to balance a combination that would last longer, and be worth the significantly higher price.

Urry tested numerous materials before settling on manganese dioxide for the cathode and solid zinc for the anode. This combination produced superior battery life, but Urry’s prototype cell could not match the power output of the company’s existing zinc-carbon batteries.

After several attempts to improve the power output from his alkaline cell, Urry found a solution. By replacing the solid zinc anode of his original prototype with zinc powder, Urry was able to increase the reactive area of the anode and improve the cell’s power output.

“My eureka moment came when I realised that using powdered zinc would give more surface area,” he recalled years later.

An estimated 80% of the dry-cell batteries in the world today are based on Urry’s work.

It goes and it goes and it goes...

He soon had a a prototype but still had to prove its value to intransigent upper management. But Urry had a plan.

He made a trip to a toy store and bought two battery-operated model cars. In one of them he put a conventional D-cell battery, while his prototype alkaline battery went in the other. Then, with RL Glover, Eveready’s vice president in charge of technology, watching, Urry set the cars loose on the floor of the plant cafeteria.

“Our car went several lengths of this long cafeteria,” Urry told the Associated Press in a 1999 interview. “The other car barely moved. Everybody was coming out of their labs to watch. They were all oohing and ahhing and cheering.”

The dramatic demonstration instantly convinced Glover of the project’s merit, and, albeit a few decades down the line, inspired Energizer’s famous ad campaign – with a drum-beating bunny that goes and goes and goes...

In fact, a few weeks later Glover provided his own demonstration of Urry’s alkaline battery to an executive in the products division in New York. Rather than using toys again, he loaded one torch with a standard battery and one with an alkaline battery, then he left them switched on overnight.

Sure enough, by the time the next morning had dawned, only the alkaline-powered torch was still shining.

“That was it,” Urry later told the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “At that point, the whole lab was put on the alkaline project.”

Portable power

The battery was – of course – an instant success. It dominated the market for decades, and even now, an estimated 80% of the dry-cell batteries in the world today are based on Urry’s work.

Over the years engineers and scientists have continued to follow in Urry’s footsteps – not least of which is Urry himself, who spent 54 years at Eveready. Gradual improvements have made modern examples of his creation last some 40 times longer than the ones that went on sale in 1959. Though they’ve been so incremental that we – the consuming public – tend to forget how impressive the lifespans of modern batteries are. We curse them for running down in barely a month of use and forget that in our childhood they barely lasted a long car journey.

In recognition of his invention, in 1999 Urry presented the first prototype alkaline battery and the first manufactured cylindrical alkaline cell to the US’ grand Smithsonian Institution. They were put on display in the same room as Thomas Edison’s famous prototype light bulb.

But Urry’s contribution to the world doesn’t just amount to making a car speed across a cafeteria floor in the 1950s – it led to the age of portable electronics.

Before his invention hit the market, batteries were unreliable and short lived and there is no way that those batteries could have powered the gadgets we use today. But by even the early 60s, if you wanted to listen to the radio you could go for a walk with your transistor, rather than being tied to a communal set in the living room.

Urry’s contribution to the world doesn’t just amount to making a car speed across a cafeteria floor in the 1950s – it led to the age of portable electronics that we now live in

Going mobile

Without the alkaline battery, portable electronics would be a pipe dream. There would be no easily portable radios, no camcorders and no loud, power-hungry toys – though your own feelings about that last one may depend on whether or not you have children.

And even though rechargeable lithium-ion batteries are now powering our phones and laptops, the portable electronics that they’re founded upon would not be a reality if it wasn’t for the generations of gadgets that used their alkaline predecessors. Without the Sony Walkman – powered by a couple of AAs – it’s hard to imagine Apple creating the iPod.

Most of the batteries used in mobile phones or other electronic products are a result of the research done by Urry during his time at Eveready. Urry revolutionised what we know as batteries and we see his work every day, but there are very few people who would ever recognise his name.

Even Urry himself kept quiet about it from day-to-day. “He took special pride around Christmas, when there was a rush for batteries,” his son Steven told reporters in the wake of his father’s death in 2004 at age 77.

“He didn’t brag on himself. It wasn’t until we got older that we realised what he had done.”

Originally published in October 2014

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.