Space mirrors and volcano drones: £56m awarded for geoengineering experiments

SCIENTISTS have been awarded more than £56m (US$74m) in funding by the UK’s moonshot innovation agency to investigate whether launching mirrors into space, thickening Arctic sea ice and disrupting clouds could reduce global temperatures.

The UK’s Advanced Research & Invention Agency (ARIA), which was established by the government in 2023 to fund high-risk, high-reward research, has announced funding for 21 research teams to look at the ethics of geoengineering, model the impacts, and begin to conduct small-scale trials.

The approaches – known as solar geoengineering – focus on preventing heat being trapped in the atmosphere or reflecting away sunlight.

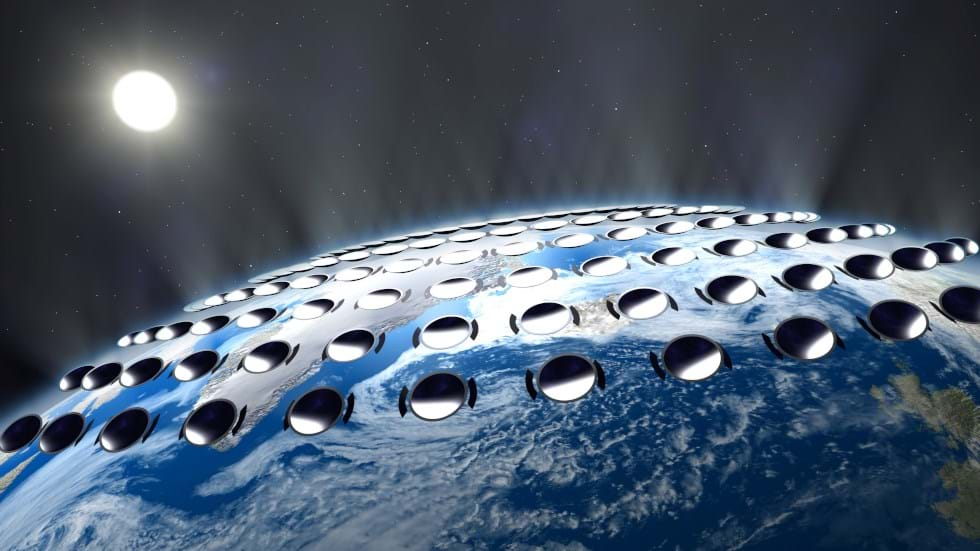

A team involving engineers at NASA and the University of Nottingham has been awarded £400,000 to model six conceptual designs for space reflectors. The idea is that giant sunshades could be launched into space to reduce the amount of light hitting Earth. Their models will simulate the potential climate impacts and provide data on which designs are worth pursuing.

Among the small-scale experiments that have been funded is a £9.9m grant for a team led by the University of Cambridge to slow the summer melt of sea ice by increasing its thickness. More ice for longer periods means Earth’s surface is more reflective so absorbs less heat. Over the next three years, they will pump seawater onto ice sheets in Canada and if the early tests show the approach is ecologically sound, they could increase the tests and attempt to thicken areas of ice measuring up to 1 km2.

Also looking to increase Earth’s reflectivity is a team led by the University of Reading which has received £2m to see if electric charge can be used to brighten clouds. The team will see how releasing an electric charge influences water droplets in clouds, which could lead to outdoor tests covering 100 m2.

Others are investigating how to modify cirrus clouds that let light in but prevent heat from escaping the atmosphere. Aria has awarded £3.6m to a team led by Imperial College London to conduct observational flights to directly measure how particles in the atmosphere, including aircraft engine soot, affect the formation of cirrus clouds. This could provide information needed to understand whether deliberately thinning cirrus clouds is a safe, predictable mechanism for cooling.

Researchers are exploring how, in the future, we might mimic the cooling effects of volcanic eruptions by deliberately injecting aerosols into the stratosphere. A team from the University of Cambridge has received £5.5m to launch balloons containing small volumes of mineral dust such as limestone and dolomite to see how stratospheric conditions could affect their properties but without releasing them into the atmosphere. Another team from the University of Bristol has £4.3m to spend designing and testing drones that can fly 10 km high to study the particles released by erupting volcanoes. The goals of the research include developing a rapid-response drone service that could be deployed to significant volcanic eruptions.

Aria is also funding five projects focused on the governance and ethics of geoengineering.

“This programme of carefully controlled research directly embodies ARIA’s core mission: tackling complex, often intractable scientific questions with the potential for profound long-term societal and economic benefit to the UK,” said Aria chair Matt Clifford. “By building the evidence for future decisions and ensuring responsible stewardship, this programme creates knowledge that could be consequential for generations to come.”

The suggestion that we engineer the planet to reverse climate change has long been a divisive topic, sparking concerns that it could produce unintentional consequences. Others argue that it will prove necessary given the high cost and slow pace of efforts to reduce emissions.

Pete Irvine, research assistant professor of Solar Geoengineering at the University of Chicago, said: “Aria’s new solar geoengineering research programme is the largest single funding effort to date and will make the UK a world leader in this field. But this programme should not be seen as a rush to develop and deploy these technologies. Aria’s broad programme of research will help advance our fundamental understanding of solar geoengineering and help to ensure that policymakers have the information they need to make informed decisions about these ideas in future.”

Stuart Haszeldine, professor of Carbon Capture and Storage at the University of Edinburgh, said: “Humans are losing the battle against climate change. Engineering cooling is necessary because in spite of measurements and meetings and international treaties during the past 70 years, the annual emissions of greenhouse gases have continued to increase.

“Projects in geoengineering will be subject to unusually strong and transparent governance. Strong public reactions have resulted from previous investigations. And novel and appropriate communication is especially needed to explain to citizens in urban and remote communities how and why this work is necessary.”

Mike Hulme, professor of Human Geography, University of Cambridge, said: “£57m is a huge amount of taxpayers’ money to be spent on this assortment of speculative technologies intended to manipulate the Earth’s climate. I say this because these technologies will always remain speculative, and unproven in the real world, until they are deployed at scale. Just because they “work” in a model, or at a micro-scale in the lab or the sky, does not mean they will cool climate safely, without unwanted side-effects, in the real world. There is therefore no way that this research can demonstrate that the technologies are safe, successful or reversible.”

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.