Hydrogen Down Under

WITH the rise of electric vehicles, and increasing climate awareness amongst the world’s population, hydrogen has returned to the global agenda. Climate advocates seek a zero-emissions fuel, and oil majors are looking to hydrogen as they seek to leverage their reservoir assets and fuel processing expertise in a climate-friendly energy economy.

This is nowhere more true than in Australia, a nation which finds itself suddenly in possession of the basis for a powerful hydrogen economy. Australia is an export nation, and mega-projects run in its blood. Now that Japan, a key export partner of Australian gas producers, has announced its commitment to a hydrogen future, Australia makes a natural choice as a supply partner. The Australians, always sensitive to movements in commodity prices, are keenly aware of this, and hydrogen development is a rare point on which both sides of politics largely agree. Whilst the promise of a A$1bn hydrogen stimulus package died with the re-election of Australia’s Conservative Party at the federal level, the state governments have been co-ordinated and effective in their efforts to push for hydrogen development.

Japan published its “Basic Hydrogen Strategy” in 2017, and the following strategic relationship development with Australia has catalysed considerable interest in the future fuel. Due to false starts in the 70s and 80s, hydrogen is still the subject of considerable scepticism within the energy community. However, by all accounts, Japan is serious about developing the technology and Alan Finkel, Australia’s Chief Scientist, has at least been convinced. Over the past few years Finkel has been a strong advocate of the hydrogen opportunity. In October 2018, he presented to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), estimating hydrogen exports of 137,000 t/y by 2025. Whilst insignificant in comparison to Australian LNG exports (soon to be the world’s largest at around 70m t/y), the opportunity has triggered a large amount of policy, project, and research support for hydrogen activities across the country (see Figure 1).

In this hydrogen-friendly climate, the past two years have seen a number of world-leading projects announced. This is good news for the development of a hydrogen economy, but it should be noted that the climate credentials of some of these projects are questionable. Significant sums have been invested in renewable-powered electrolysis projects, but they have also been invested in strongly CO₂-emitting brown coal gasification. It is clear that Australia is interested in hydrogen, but it is still an each-way bet as to whether the industry and the government will choose the polluting path or the ‘clean’ one.

One of the most well-known projects, and probably the most controversial, is the coal seam gas project in the Latrobe valley of Victoria. The Latrobe valley is one of Australia’s largest coal regions, and a flare point for much of the country’s politics. Receiving A$100m in government support, the Latrobe hydrogen project could easily be seen as a political move, attempting to bridge the ever-widening gap between supporters of the coal industry and those calling for climate action. The hydrogen will be extracted from coal gasification in the region, but it is as yet unclear what will be done with the resultant CO₂, and whether it will be captured and injected back underground. The industrially interesting test lies in the port facility, for which Kawasaki has recently announced its intent to construct a A$500m hydrogen liquefaction and export terminal. The incredibly cold temperatures required for hydrogen liquefaction (around -254°C) will require extensive engineering consideration and design; and success depends upon handling these factors appropriately. At this stage, the project is just a pilot, consuming 160 t of coal, generating 100 t of CO₂ and producing only 3 t of hydrogen over its 12-month duration. It is unclear what steps will be taken after the completion of this phase but, as the maxim goes: “From little things, big things grow”; proving the concept in Latrobe may be the first step to much more extensive investments in future years.

Whilst ‘brown’ (CO₂ released) and ‘blue’ (CO₂ captured) hydrogen from steam reforming have certainly been of interest in the country, Australia’s renewable hydrogen proposals have so far dwarfed those of fossil-based projects. With the precipitous drop in the cost of solar and wind power (around 70% for wind, and 90% for solar) in the past decade, many believe that the cost of hydrogen will begin to follow the same downwards trajectory. Such a movement could cause fundamental changes in energy market economics and Australia’s abundance of land, sun, and wind has lured many large organisations to pursue this opportunity.

Both the Yara ammonia plant in Western Australia, and Neoen’s Hydrogen Super Hub in South Australia have announced the upcoming construction of 50 MW solar/wind-powered electrolysers for the production of ‘green’ hydrogen. This is significant, and if deployed today, either of these projects would be the largest of their kind in the world. In addition to these specifically hydrogen-focused deployments, an increasing number of renewables projects are also incorporating hydrogen development for grid balancing activities. The Asian Renewable Hub, an enormous 15 GW renewable park proposal aiming to deploy solar and wind energy in Australia’s North-West, has also made clear its intention to deploy hydrogen electrolysis to make use of electricity in off-peak periods.

Whilst the industry is developing, some clear challenges remain. Particularly, shipping of hydrogen fuel is not a trivial task. Australian innovation, in the form of start-ups and government-funded research, is attempting to work around some of these barriers. One of the most interesting developments is that from CSIRO, the country’s national science institution, announcing key advancements in the reversible conversion of hydrogen to ammonia. This is a key innovation for hydrogen, as ammonia carries much more energy per unit volume and liquefies much more readily. If CSIRO continues to achieve progress in this direction, it is hoped that the easy inter-conversion between hydrogen and ammonia will drastically reduce the cost of shipping the fuel.

Another key piece of technology lies in the abatement of CO₂ from fossil-based hydrogen projects (recall the earlier figure of 70m t/y in LNG exports). If carbon capture and storage becomes commercially viable, steam-reforming of methane to produce blue hydrogen from Australia’s abundant natural gas reservoirs could become a mainstream practice. This opportunity, coupled with the fear of climate-related political action, means that Australia is keenly looking for a solution to this problem. So much so, that the Australian CO2CRC research council maintains the world’s largest carbon capture research and storage demonstration project. Since 2007, the council has allocated over A$100m of government funds to end-to-end CO₂ production and sequestration research (see Figure 2).

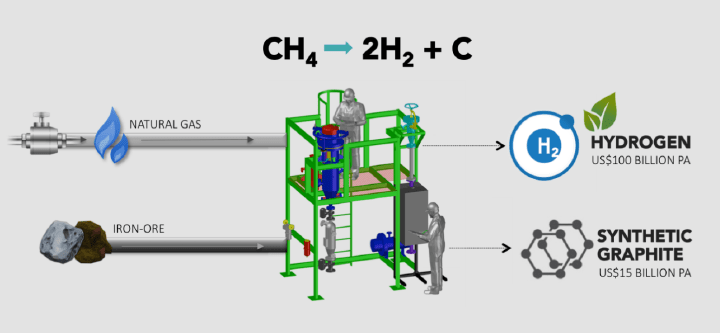

One particularly interesting solution to the carbon capture problem is found in the Australian startup Hazer Group. Hazer is currently in the pilot stages of commercialising an innovative carbon-capture technology in which CO₂ production is completely avoided (see Figure 3). Based on methane cracking technology out of the University of Western Australia, the group aims to transform methane directly into graphite and hydrogen using a cheap iron ore catalyst. Such a process would eliminate the need for expensive CO₂ capture and has the potential to be disruptive if proven at larger scales. Successful development of these carbon abatement technologies could be a game-changer for fossil fuel companies seeking to adapt to our changing energy system. If this sleeping giant of the hydrogen economy is woken, it could lead to rapid and large-scale deployment of hydrogen energy globally.

Whilst the export opportunity is large, the attention being paid to the area has also led to interest in domestic applications. Much of the Australian housing system still has gas connections, and several projects are looking at distributing hydrogen throughout the network. The gas network operator in Western Australia, ATCO Gas, built and unveiled a ‘green’ hydrogen facility in July, and is injecting a low concentration of hydrogen into the local network for use in homes. Virtually the same activity is also being carried out in Sydney by the gas retailer Jemena, arguing that customers are increasingly looking for sustainable solutions. The existence of these projects signals an unserved need in the Australian market; namely that households want their gas connections, but that they also want to lower their carbon footprint. As these projects develop, it will be interesting to see exactly how widespread the demand is for carbon-neutral fuel.

Energy is a vital part of Australia’s economy; it has been, and will continue to be, a vital source of jobs, prosperity and political power in the country over the coming years. Unlike other green energy technologies, hydrogen can be a fuel, and stands to provide an important component of the energy mix as the world decarbonises. Exports can be sent to nations without renewable resources, and it is reasonable to assume that the geopolitics of energy supply chains will shift significantly if hydrogen exports are proven viable in the next decade. Whether or not hydrogen will become a dominant player is an open question, but observers would do well to pay attention to Australia’s movements in the coming years.

This is the 12th article in a series discussing the challenges and opportunities of the hydrogen economy, developed in partnership with IChemE’s Clean Energy Special Interest Group. To read more from the series online, visit the series hub.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.