A Wasted Life

Martin Pitt reflects on the history of the waste industry, including his own experiences

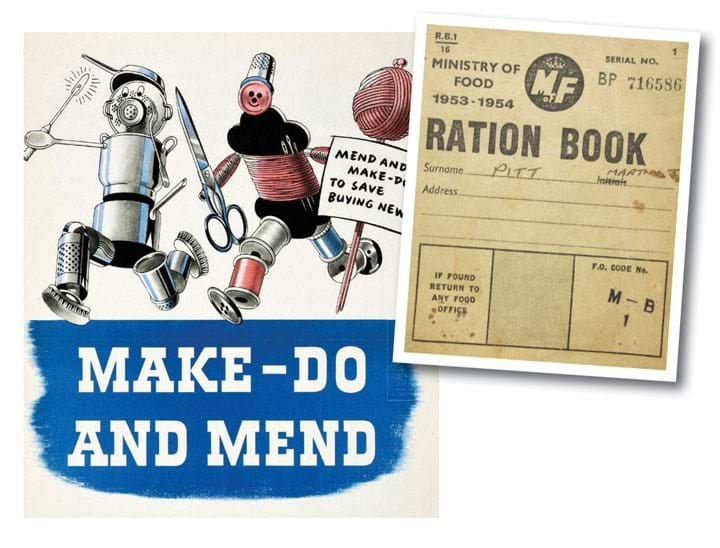

FOR the first 10% of my life, food was rationed. Rationing did not stop with the end of WWII but continued until supplies had been improved sufficiently, though not plentiful. Discarding food would have been as unthinkable as discarding ten-pound notes. It is still hard for me not to clear a plate. In the rest of life, things were repaired and reused, and this is still my instinct. I have also been professionally involved in waste treatment and recovery.

Landfill

In the early 70s, I attended a conference on waste treatment and recycling in which one delegate declared “I don’t know what all the fuss is about. We’ve got plenty of holes in the ground.” This has unfortunately been a common attitude for waste of all sorts, being discarded to land, water and air at low cost to the producer.

In the early 80s I worked for a company, part of a group which included a manufacturer of bricks, for which it mined clay. It turned out that filling the hole with industrial and domestic waste was more profitable than mining it and making bricks had been, because the clay prevented toxic materials seeping away. Suitable holes in the ground were becoming more and more valuable and the cost of a volume of waste went up and up.

Landfill in precious holes in the ground was the standard method of dealing with household rubbish from Victorian times. However, during WWII the Refuse Departments of major cities became Salvage Departments. Efforts were made to recover everything of value from domestic and industrial waste. My father was responsible for maintenance of one of these and he remarked to me what a terrible job it was for the people who picked items off conveyor belts, and how glad he was when they stopped in the 1960s. Who would guess that we would be doing that in 2022? Electric dustcarts were stopped at about the same time, but are starting to come back.

“I don’t know what all the fuss is about. We’ve got plenty of holes in the ground.” This has unfortunately been a common attitude for waste of all sorts, being discarded to land, water and air at low cost to the producer

Incineration

To reduce the volume and cost of landfill, refuse can be incinerated, leaving only ash. The first was in 1874 in Nottingham, UK and naturally they used the heat to raise steam. However, municipal incinerators built a hundred years later were optimised for destruction, not energy recovery. They were common but not popular locally. I was not the only one who thought it was a pity that they just wasted energy as flue gas. Dust and acid scrubbing were used, but there was no thought about CO2.

District heating had been introduced in the UK after WWII, utilising waste heat from power stations for new estates replacing bombed ones. It was only in 1988 that IChemE Fellow Jim Swithenbank, of Sheffield University, persuaded the city to create a system in which refuse incineration provided heat through pipes. This was not just about pipes and pumps; the whole combustion system was designed and modelled with the new Fluent software which he had created jointly with Hans Ferit Boysan. A challenging task for what proved to be a major chemical engineering tool to manage flows of matter and heat and chemical reactions in three dimensions.

It now provides heat to the University, the Hospital and some industry. There are similar arrangements in a number of European cities. Leeds has an incinerator where the refuse is burned to generate electricity, with a plan for district heating in future.

A problem with both of these comes with the current practice of waste segregation by the consumer. If the majority of paper and plastic is removed, then the calorific value of the remainder is below the original design specification, and it is necessary to mix some back in. In addition, for the Leeds incinerator, it is supposed to be sorted automatically and was set an ambitious target for recycling. However, having had much of the recyclable material removed, this was not achieved. In my view it also meant unnecessary capital and running costs for what is in practice only a few per cent of “black bin” (non-recyclable) waste.

Sewage

Dustbins are not the only source of waste in cities and towns.

Sewage is an increasing problem. The principal unit operation is settling and filtration with a filter press, a process which has been going on for more than a hundred years. Originally, the solid was also dumped to landfill. It could not, as you might suppose, be used for fertiliser because it contained soap and grease which was harmful to the soil structure.

About 100 years after flush toilets came into use, in 1912, with great ceremony, the Mayor of Oldham opened a sewage plant designed by chemical engineer Jacob Grossman (Times, 28 Oct 1912). Unlike other sewage plants, it made a useful profit from recovered materials. The sewage was filtered and mixed with acid to crack the soap. Steam was then passed through to sterilise the solid and distil out fatty acids suitable for making new soap and other products in the chemical industry. The dried residue was a sterile brown powder, a good fertiliser and soil conditioner. It also freed up land which would otherwise be used. Grossman estimated that the widespread treatment of sewage could provide the UK with the equivalent of 50,000 t of phosphate fertiliser per year as well as some nitrogen and potassium.

It did not appear to take off, but 101 years later a treatment plant in Slough opened, also recovering phosphate and nitrogen as white crystals rather than brown powder, estimating that the UK could recover 30,000 t of phosphate, a fifth of current imports. This is now more commercially widespread. The product is advertised as made by “nutrient recovery” rather than “made from poo”.

Effluent

It is not commonly realised that the wastewater treatment plant on a chemical works is a critical component. If that has to stop, then the plant has to stop, as soon as any on-site storage is filled.

In the late 70s I worked for a company which produced phenol and related products. As a result there was often some phenol content in site water. Fortunately the microorganisms in the effluent treatment plant had been trained to eat it. However, one day the labs flushed several kilograms of sugar down the drains. It turned out that the bugs only munched on phenol when there was nothing else. Given the choice of sugar, they fed on that, and the phenol came through, violating our discharge consent.

Later I managed a plant which neutralised acid waste and filtered the precipitate to give a solid which could be deposited to landfill as non-hazardous waste and water which was acceptable to the sewer. This greatly reduced the magnitude as well as the difficulty and cost of disposal. We also treated some sludges and suspensions by appropriate treatment (neutralisation and flocculation) and filtration.

It had (as usual) bunds around acid storage tanks. Because it rains in Britain we had to sample the water which collected in them before releasing it to drains. After I left, a subsequent plant manager, with storage tanks being full, decided to temporarily store some weak acid sludge in the bund. Unfortunately the brickwork was not up to it and one wall gave way. The manager of the adjacent company was not pleased to have his Porsche exposed to this. I had different employment by then, so I don’t know what the consequences were.

It is not commonly realised that the wastewater treatment plant on a chemical works is a critical component. If that has to stop, then the plant has to stop, as soon as any on-site storage is filled

Plastic – not so fantastic?

In India in 1986 I had some tea on the train. It was brought to me by a chaiwala with disposable cups obviously made in a few seconds by hand from clay. When people had finished they threw them out of the open windows where they crumbled back into the dirt and vanished. Some weeks later, I had tea from a more modern vendor who supplied foam polystyrene cups. The litter from them was evident along the track.

Plastic is the main example where the problem is not with the substance but the lack of care in dealing with the end of life, and a commercial environment of throw-away and buy new. It is the very success of chemical engineering that means production has increased and costs have dropped. A mobile phone discarded in favour of the new model has capabilities that would have cost millions earlier within the lifetime of many users.

Waste has always been dealt with in the cheapest possible way, low wage and low tech, often on the principle “out of sight out of mind”.

Fifty years ago the environmental solution was degradable plastics, and many techniques were excitedly promoted in the media. What they mainly did was to have weak links between polymer particles so that the object crumbled into dust. Or as we now call it – microplastics (a term only invented in 2004) and worse than bulk items. The automatic washing machine and promotion of cleaning (and cleaning products) has also proved an effective way of generating a major environmental hazard from synthetic fibre clothing.

Recycling is possible, but the practical problem is separation, since there are a vast number of types and they only rarely come in single substance forms. PET or polythene bottles are one example, but many commercial products use several plastics plus other material as fillers, colours or reinforcing.

One option is pyrolysis to oil and gas, something I studied in my 1979 MPhil, and which is now in limited industrial use.

Waste has always been dealt with in the cheapest possible way, low wage and low tech, often on the principle “out of sight out of mind”

A better future

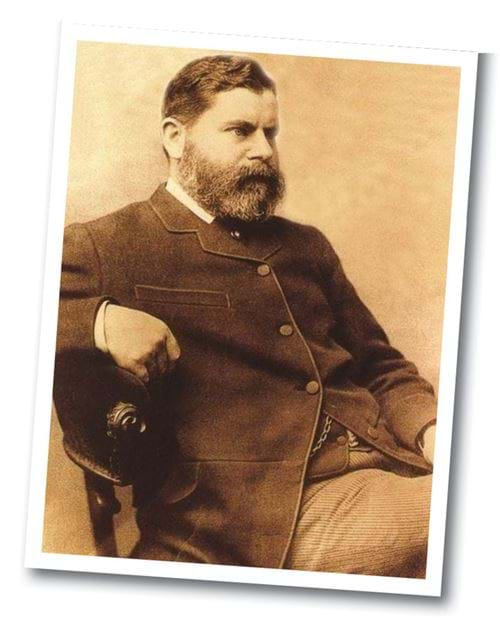

And what of chemical waste? It was of course the terrible environmental damage from the 19th Century British chemical industry that motivated George Davis to publish his Handbook of Chemical Engineering to show how good practice could give more efficient processes, saving money for the factory and reducing the burden on people and the environment. Since the beginning of IChemE, the habit of a mass and energy balance has been part of the profession, and recycling calculations are normal first-year teaching. We perhaps do not appreciate how obvious it is to us and how novel it is to others. I am pleased to see how much chemical engineers are contributing to low-waste processes and environmental sustainability, and hope these ideas can be more widely understood, so that the future is less wasteful than the past.

For more on IChemE’s Centenary, including historical reflections from IChemE members, visit the dedicated website: www.chemengevolution.org

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.