Turnaround Scope Optimisation

Gordon Lawrence discusses the importance of prescriptive scope criteria in a turnaround premise document

IT IS generally accepted in the maintenance turnaround community that the larger and more complex a turnaround becomes, the more difficult it is to control costs and schedule. An obvious, but generally overlooked route to ensure a turnaround is no larger than it needs to be, is to ensure that only the necessary scope is included in the turnaround event.

The best way to ensure that this happens, is to include very clear, prescriptive scope criteria in the turnaround premise document that is issued at the start of preparation and planning. Unfortunately, too many teams write premise documents that focus only on the tactical targets of turnaround event cost and schedule and ignore the strategic issue of defining what the purpose and objective of the turnaround event is. This article explains what information is important to include in a premise document and lays out an example template for teams to follow. By using this template, teams will be armed with strong scope criteria and the means to combat scope growth in their turnaround preparations.

Complexity increases turnaround predictability risks

Maintenance turnarounds are significant events in the long-range plan of any refinery, petrochemical plant, offshore production asset or other facility that uses large, continuous production process plant. Whether a turnaround was executed predictably, within its cost and schedule targets, is typically one of the leading measures used to assess whether a turnaround can be judged to have been a success.

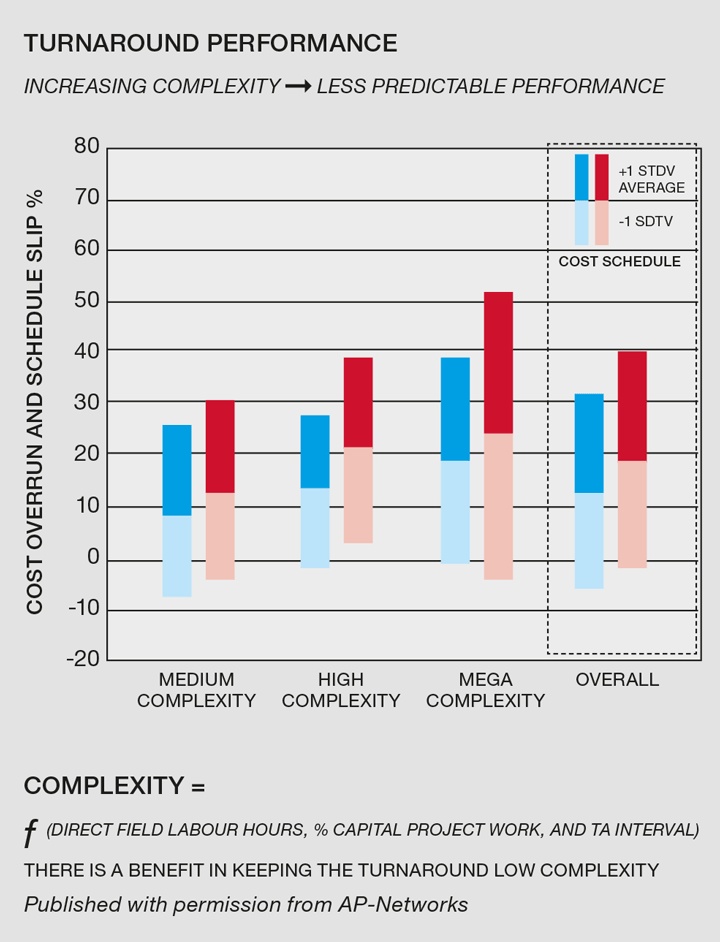

It has been known for some time that the size and complexity of a turnaround tends to correlate with the likelihood of being able to achieve a predictable cost and schedule. Larger turnarounds, with more scope and consequently more field labour hours tend to be less easy to keep within cost and schedule targets than smaller, simpler turnarounds. The turnaround consultancy, Asset Performance Networks LLC (for which I previously worked) even goes so far as to publish comparisons of average cost and schedule overrun for low, medium, high and mega-complexity turnarounds at its annual conference every year (https://bit.ly/3qQipAt). It assesses turnaround complexity as a function of (a) scope size, in terms of direct field labour hours, (b) the proportion of the scope that is related to capital project work, and (c) the length of the interval between turnarounds on the asset (https://bit.ly/3rqO6R1). The latest publication from AP-Networks (2019) is shown in Figure 1 and clearly illustrates how the risk of overrun increases with increasing complexity.

Frequent and small, versus infrequent and large turnarounds

Knowing that scope size relates to event predictability it would be logical to assume that assets would focus on smaller turnarounds. However, this assumption comes up hard against the trend in recent years, particularly in the onshore refining and petrochemical industry, to extend the interval between turnarounds to allow for longer production runs. But a longer run means more corrective maintenance when the turnaround finally does come around, and so the trend has been towards bigger and bigger turnaround events. (Whether this trend will slow or reverse, to take account of social distancing rules related to Covid-19, is still to be discovered.)

Executing the necessary scope, versus executing the preferred scope

One way in which turnaround planning teams can accommodate the push towards longer intervals, whilst still taking account of the knowledge that more complex turnarounds carry greater risk of overrun, is by focussing on the work scope that “needs” to be done, as opposed to that which operations and maintenance would “like” to be done.

Even today, in the offshore industry, the focus on many assets is still on seeing how much scope can be executed in a given time, not on how much time is needed for a given scope

It is likely that many turnaround managers can quote examples of turnarounds whose scope was swollen by work that could have been done “on the run” during daily maintenance, but which the routine maintenance team deemed too expensive, too unsafe, or even simply too tiresome to do on the run and so moved it to the turnaround scope; or preventive maintenance where the risk of future failure was low, but operations insisted on including in the turnaround in order to reduce still further the risk of breakdown during the operational run. Even today, in the offshore industry, the focus on many assets is still on seeing how much scope can be executed in a given time, not on how much time is needed for a given scope.1

Robust scope challenge

Industry has now begun to pay attention to the idea of focussing on necessary scope, rather than desired scope. Many firms and many assets have embraced the concept of risk-based scope review (RBSR), to challenge whether each preventive maintenance scope item should be included.2

However, before the RBSR, there is an earlier step, which many firms are still failing to execute properly. This earlier step addresses not only the preventive maintenance scope but also all other scope, including corrective maintenance, inspections and projects. That step is to define clear and prescriptive scope inclusion criteria and then use those criteria as the first screen of whether a scope item should be included.

The role of the turnaround premise document

The logical location for those scope criteria is in the turnaround premise document. The premise document is, or should be, the foundation document for any turnaround event. It should describe the turnaround event, spelling out the event objectives and performance indicators. However, too many assets take a simplistic approach to the contents of the premise document, focussing firstly on what will be shut down, without explaining why it will be shut down; and secondly on the key performance indicators (KPIs) for the turnaround team, of safety, cost and schedule. In this form, the premise document becomes little more than a stick with which to beat the turnaround team, to berate them as they attempt to meet the KPIs set for them.

A far better use of the premise document is to construct it such that its contents can be used to control and guide the scope of the turnaround event. In this way it is a stronger tool for the turnaround team, allowing them to robustly challenge all scope requests; whilst at the same time it retains its usefulness to corporate and asset leadership as a tool to ensure the turnaround meets the business objectives.

The contents of the turnaround premise document

Most owners and asset leadership teams recognise that the premise document should include targets for the turnaround team to meet, such as a safety goal, an event cost goal and a schedule goal for the turnaround execution window. However, these are tactical goals against which the effectiveness of the turnaround preparation, planning and execution team can be measured.

The more significant information that should be in a premise document is the strategic information about the turnaround; the reasons why the event is taking place and hence what the asset must be capable of, once the event is complete. From this why and what, the scope criteria will then easily flow. The scope criteria define the rules by which a scope item should be assessed for inclusion in the event.

Why the turnaround event is needed

So, the first issue to address in the premise document is the reasons why the event needs to take place at all. For this is useful to first discuss the long-range plan for the asset. Discussing the long-range plan allows the document to explain the overall strategy of total asset or partial asset shutdowns, upcoming capital investment plans and hence the overall cycle of turnaround intervals over the coming 12 years or so.

This discussion then leads smoothly into why the turnaround is needed. The reasons generally fall in three broad categories:

1. RETAINING THE LICENCE TO OPERATE

The discussion under this heading would cover: Statutory inspections that are coming due by a certain date within the turnaround interval; projects that are required in order to comply with upcoming legislation; and safety-critical maintenance.

2. MAINTAINING PRODUCTION

The discussion under this heading would cover the need to maintain and clean the asset, in order to ensure that production can be maintained.

3. UPGRADING THE ASSET

The discussion under this heading would cover any projects which the long-range plan for the asset dictates need to be tied in by the time the turnaround is due to be complete.

The desired end-state of the asset

It should now become more apparent, that having discussed the long-range plan and laid out why the turnaround needs to take place, it becomes simple to spell out what the end-state of the asset should be, by the time the turnaround is complete. An example text might be: “Once the turnaround is complete, the asset must be capable of running for 6 years, at X throughput, with a maximum of Y unplanned downtime during the 6-year run. Achieving throughput X will require that project Z is successfully tied in and commissioned as part of the turnaround event.”

Specific scope selection criteria

Armed with the statement of the desired end-state, it now follows that the premise can lay out the scope selection criteria that are specific to this turnaround. These criteria can usefully be grouped under the same headings as were used to describe why the turnaround needs to occur. Example text might be:

1. RETAINING THE LICENCE TO OPERATE

- Statutory inspections: All statutory inspections that fall due before [date of the following turnaround] are to be completed by the end of this turnaround.

- Compliance with upcoming legislation: Regulation X comes into force before [date of the following turnaround]. Therefore Project Y is to be completed, tied-in and commissioned by the end of this turnaround.

- Safety-critical maintenance: All corrective maintenance that is safety critical will be completed by the end of this turnaround.

2. MAINTAINING PRODUCTION

- All corrective maintenance necessary to enable the asset to be capable of running for 6 years, at X throughput, with a maximum of Y unplanned downtime during the 6-year run.

- All preventive maintenance that a risk-based assessment determines would jeopardise the target of Y unplanned downtime.

- All cleaning necessary to enable the asset to be capable of running for 6 years, at X throughput.

- All catalyst changes required to meet the run length specified.

- Reliability inspections required to provide reliability data for the future.

- Management-of-change work to meet the reliability target specified.

- Inspections required by original equipment manufacturers to validate guarantees.

3. UPGRADING THE ASSET

- Projects that are required to meet the long-range plan for the asset, including debottlenecking, production increases, running cost reduction projects and feed/product slate modification projects.

These specific scope selection criteria are a key requirement to form the basis for any scope challenge during a risk-based scope review. They provide firm rules with which to challenge whether a scope item should be included in the turnaround.

General scope selection criteria

The second key requirement for any scope challenge is the set of general scope selection criteria. These are the general rules that most teams think of, when asked to name any scope selection criteria. Examples of common general rules include:

ON-THE-RUN

If work can be done safely on the run, it should be done on-the-run and not included in the turnaround. If the only reason it cannot be done on-the-run is because the isolation valves are passing, then only the isolation valves will be included in the scope.

SLOWDOWN/PITSTOP

If work can be done during a slowdown or pitstop then this is to be considered during the risk-based scope review, and the most economical option chosen.

REPAIR VERSUS REPLACE

If the time taken to repair causes schedule lost production opportunity (LPO) costs that exceed the replacement cost, the item will be replaced.

PROJECT WORK

Project scope: Project work in the turnaround is to be limited to tie-ins only. In addition, where possible, projects are to design work in order to maximise non-turnaround scope and minimise turnaround scope (eg replacement pumps should be built on new plinths, and not reuse existing plinths).

Project preparation: Discuss whether projects have to meet certain turnaround preparation milestones or risk being dropped from scope. (Discuss the trade-off of risk to the turnaround execution versus value of the completed project to the asset or facility.)

Future project ideas: Discuss the point that any future project ideas, no matter how valuable to the asset or facility, will need to be subjected to the same risk-reward tradeoff discussion mentioned above.

Tactical objectives for the turnaround team

The final element of the project premise to include is the targets for the turnaround team in the execution of the turnaround. Typically, these include: health and safety during field execution; environmental targets during field execution; quality and startup targets; budget competitiveness and predictability; and execution schedule competitiveness and predictability.

Conclusion

The leadership on most assets uses the turnaround premise document as repository for general scope criteria rules and for tactical objectives for the turnaround team. Very few use the premise to its full advantage, by including strategic objectives and detailed, prescriptive specific scope criteria. Those assets and turnaround teams that do include strategic objectives and specific scope criteria have found that this provides a clear vision of what the end state of the asset should be after the turnaround and provides the turnaround team with a firm basis for challenging and controlling scope.

If each person submitting a scope item first has to specify how that item meets the specific scope criteria and contributes to the strategic objectives, this is a powerful filter to ensure that only the necessary scope is included and not the preferred scope. In this way, the overall turnaround event scope is constrained to the optimum size and the risk of an unpredictable cost or schedule outcome is mitigated.

References

1. Lawrence, GR, “C Minus-: Room for Improvement”, Offshore Engineering (OE), August 2017, pp38-40.

2. Two examples are: https://bit.ly/3dFMjUj and https://bit.ly/3dLL4mC

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.