The Power of Listening

LISTENING is probably the most important skill we use in our professional and personal lives. It underpins every face-to-face interaction, and therefore is at the heart of leadership, teamwork, negotiation, collaboration and training. Most people would describe themselves as a “good listener”. Given that listening is so important, how might you become better at it?

When I ask people how they feel when someone really listens to them, I get words like valued, appreciated, unrushed, and creative. When I ask people how they feel when someone does not listen to them, I get words like frustrated, unappreciated, unimportant, angry and disengaged.

Immediately, we have some powerful information. If we want the people around us to feel valued, appreciated, unrushed and creative we just need to listen to them. If the people around us feel that we are not listening to them (even if we are), they will feel frustrated and disengaged. The act of listening costs us nothing and has a significant and positive impact on the people around us. The act of not listening has a significant negative impact on the people around us, and costs us dearly in terms of disengaged teams and dysfunctional relationships.

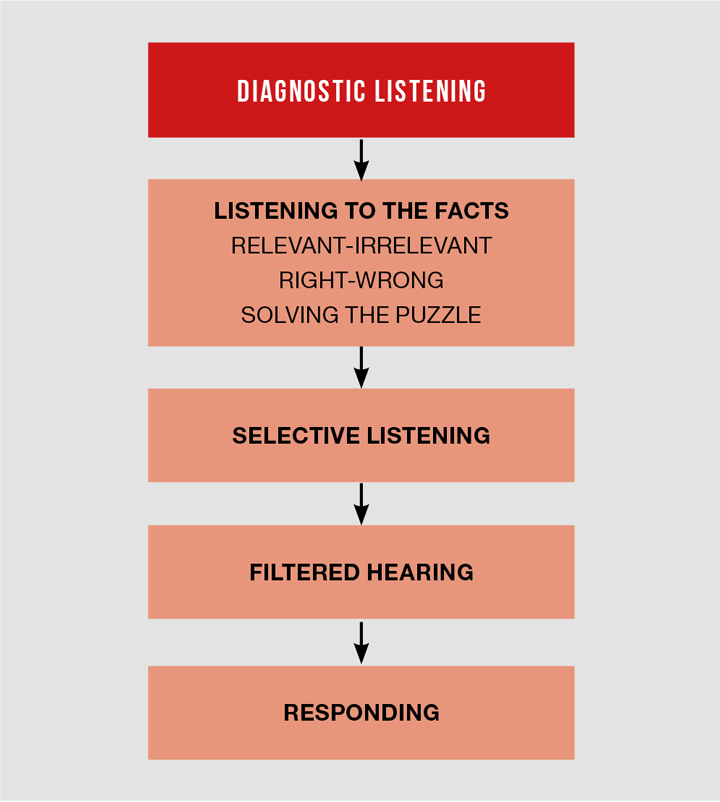

Given that listening is good, let’s take a look at how we listen. Most engineers are good at what’s called diagnostic listening. It’s been part of our training, and serves us well when faced with a technical problem. We listen to the facts, and start a selective logical process to diagnose the problem and prescribe a solution. We sort out what is relevant from what is irrelevant, and what is right from what is wrong. We develop a hypothesis and follow it.

The danger of diagnostic listening is that we become selective in our listening, and start to filter our hearing. We subconsciously tune in to things that support our hypothesis. First, we may be missing some vital information if our hypothesis is flawed. Secondly, and more importantly, in diagnostic listening we are listening to the facts, and therefore not listening to the person. The speaker may begin to feel frustrated, unappreciated, unimportant, angry and disengaged. Diagnostic listening is therefore of limited use. It places emphasis on the facts not the person. It is also a convergent process which will hinder ideas generation and creativity.

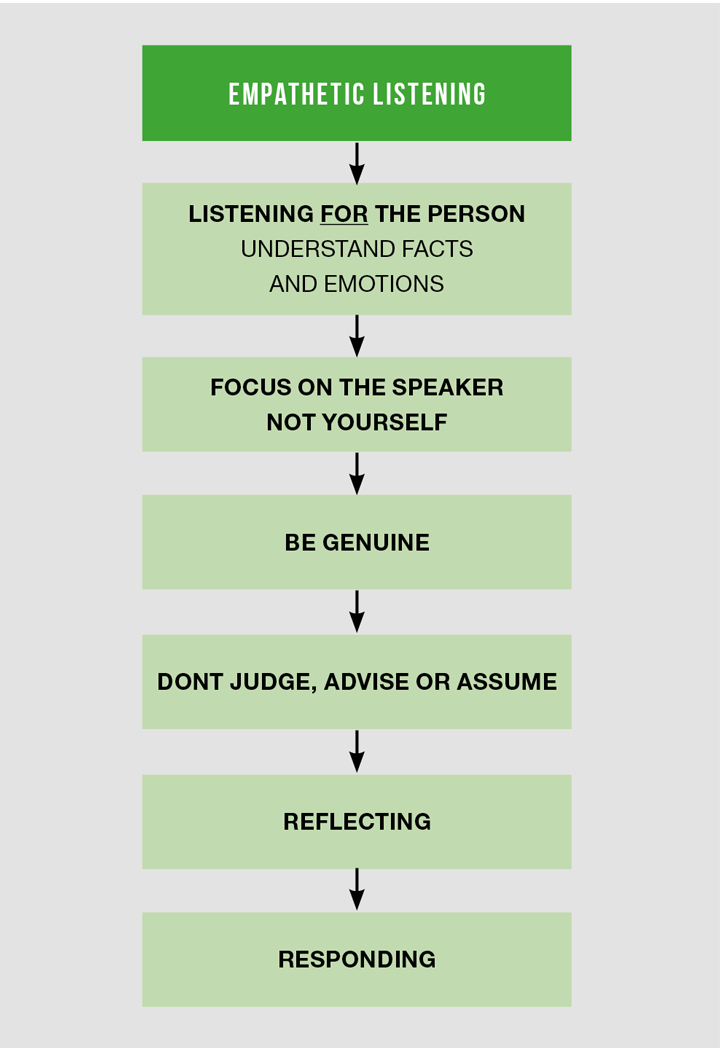

Earlier in this blog series we took a look at empathy, the ability to put ourselves in the mental shoes of other people. We established that along with body language, listening is the main mechanism by which we empathise. This leads us to an alternative listening approach, called empathetic listening. This comes from Stephen Covey’s excellent book, 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

In empathetic listening, we listen for the person, using our eyes, ears and heart, temporarily putting our own agenda to one side. As Covey says, “seek first to understand, then be understood.” This is hard. We are used to listening to people for our own benefit, either to get information, or to get our own point across.

Empathetic listening requires us to be genuinely focussed on the speaker, without judgement, advising or making assumptions. It is empathetic listening that engenders the positive response of feeling valued, appreciated, unrushed, and creative. Once we have listened, to get the full picture, we can reflect back our understanding of the facts and emotions, and respond appropriately.

Empathetic listening should not be reserved for occasions when someone is a bit upset. It is effective in sales, negotiation and in discussing technical problems, and in everyday interactions with people at work and at home. Please give it a try.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.