Pollution Protection for the People

In the second of a series about chemical engineers who are volunteering their skills to contribute to society, Clare Sheppard shares her work on urban air quality in Australia

THE INNER western suburbs of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia have a long industrial history dating back to the early days of European settlement. As the city has grown, industrial precincts have become surrounded by residential areas. Ideas on what are acceptable effluent and emissions from industry have changed dramatically, and environmental protection legislation has been in place since the 1970s.

In August 2018 a large stockpile of waste dangerous goods was illegally stored in an industrial warehouse about 1.2 km from my home. A fire at the site on 30 August 2018 burned out of control for more than 12 hours, sending a black plume of toxic smoke over nearby homes, businesses and schools.

Firefighting water runoff ran directly into the adjacent waterway, Stony Creek. The chemicals in the firewater included herbicides, hydrocarbons and phenol, which killed all life within the creek. Some firefighters who attended have had severe, chronic health impacts. This event was one of a series of large waste stockpile fires across industrial areas of Melbourne. Each one had environmental impacts which raised concerns about the role of the environmental regulator (EPA Victoria), the workplace health and safety regulator (WorkSafe Victoria), and local councils in managing and regulating industrial waste.

The residents of Melbourne’s inner west have become more concerned and vocal about emissions impacts, particularly as a major road and tunnel building project is underway. In response to these concerns the State Government formed the Inner West Air Quality Community Reference Group (IWAQCRG). The group would report back to the Victorian State Government the results of an investigation into air quality issues affecting residents of the Inner West. Membership included representatives of the planning department of each of the three local council areas (Maribyrnong, Brimbank and Hobsons Bay), local resident representatives, and a representative from each of a number of local resident groups. I became aware of the call for applications via social media, and applied. Whilst the illegal waste stockpile fire was outside the scope of the Community Reference Group (CRG) my outrage over the impacts on our community was still fresh. I was accepted to be one of two resident representatives of the City of Maribyrnong local government area. Without exception, every person who was selected to be part of the group was passionate about the area where we live and was a volunteer in multiple groups and roles.

I strongly felt that my experience as a process engineer could be useful to the Inner West Air Quality Community Reference Group (IWAQCRG). But I also felt that I could learn a great deal about environmental regulation and planning

I strongly felt that my experience as a process engineer could be useful to the IWAQCRG. But I also felt that I could learn a great deal about environmental regulation and planning in Victoria. I work in design consulting as a Principal Process Engineer in all phases of design as well as commissioning. None of the sites I have worked on were located in the area of the study. The CRG was convened by the state government Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) and it arranged presentations to the group from those we requested to hear from. We heard from health professionals and academics about health impacts of air pollution and we heard from some of the most senior personnel at EPA Victoria and DELWP. We were treated with the same respect as if they were reporting to the government. We heard from people I would never have been in the same room with during my day job. My job in process engineering design consulting has rarely required me to interact directly with regulators, as this is a client responsibility. Many of the individuals who presented to us spoke candidly and gave their personal opinions. This helped me to understand the challenge of what we were trying to achieve; promoting change at multiple levels of government across many portfolios and large government organisations.

The CRG considered the following:

- health effects of air pollution;

- monitoring, analysis and reporting of air quality;

- regulatory and policy environment;

- emissions from transport including cars, trucks, trains and shipping;

- air quality impacts of the tunnel project; and

- industrial emissions including dust and odour.

CRG members were asked to select two of these areas to draft the report for. We were all welcome to review all the draft sections. We developed a set of 26 recommendations collaboratively and then participated in a workshop to effectively group and prioritise the 66 supporting actions.

Health effects of air pollution

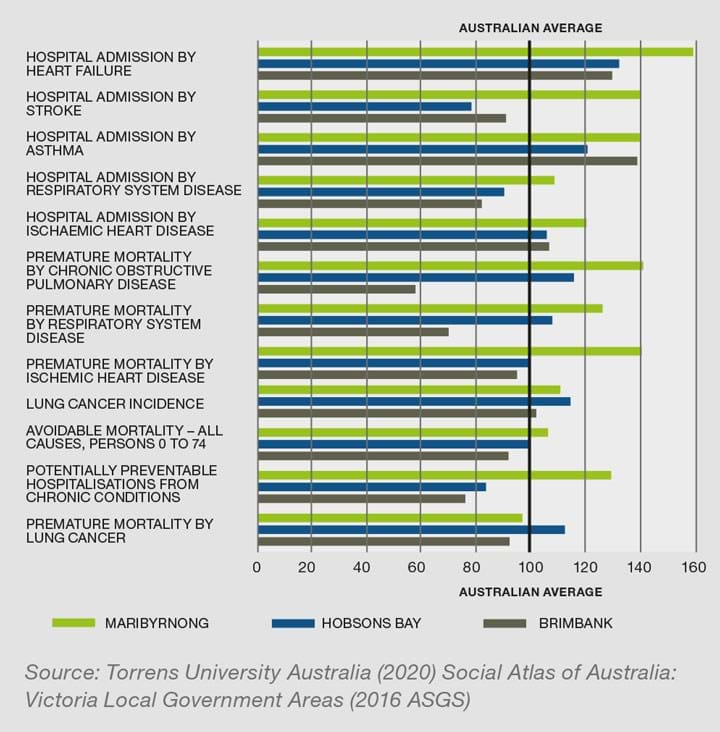

Significant health impacts resulting from poor air quality include coronary heart disease, stroke, lung cancer and asthma. Maribyrnong municipal area has asthma rates in adolescents of 16.8%, significantly higher than the Victorian average of 11.6%. When comparing the conditions which may occur as a result of air pollution in Maribyrnong, Hobsons Bay and Brimbank, the frequency of many key indicators (such as hospitalisation or death) are higher than the Australian average (see Figure 1).

The higher burden of disease is not explained by age, smoking rates, socio-economic indicators or obesity. We did not consider it unreasonable to suggest that air pollution could be the cause.

The impacts on human health create significant costs for the Victorian Government. The economic impacts on individuals and the whole community are serious. The seriousness of long-term exposure is poorly understood within the community.

Monitoring, analysis and reporting of air quality

EPA Victoria maintains and reports data for only three permanent air quality monitoring stations within the CRG reference area. Siting of the monitoring stations is intended to measure “background” air quality away from any point sources, including main roads. The CRG felt that this was insufficient, as it cannot identify the worst locations or help to identify point sources which might be able to be mitigated. The communication of measurement of “very poor” or “extremely poor” air quality to those who are sensitive to poor air quality is not timely or does not occur at all. Communication to schools in the absence of government directives and procedures fails to protect children from pollution. Schools are typically located on main roads and hence will have poorer air quality than that measured.

Six air quality monitoring stations were established along the main freeway corridor and are maintained and reported on by the tunnel building authority. Again, there are issues with the communication of these results to residents as they report against intervention levels. These are more lenient than the air quality objectives used by the EPA, leading to an under-representation of the severity of the pollution.

Polluters are generally not required to continuously monitor their own emissions. Periodic testing may occur.

Many Australian air quality standards are much lower than international best-practice standards. The average PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations regularly exceed the annual reporting standards, particularly within the freeway corridor, with no consequences.

Regulatory and policy environment

We found that policy, legislation and regulation mechanisms do not apply sufficient weight to health and amenity, and – by extension – air quality impacts. Criteria for approval emphasise economic benefits, and downplay air quality considerations. Often, cumulative impacts of multiple emission points are not considered and local council planning officers have inadequate knowledge to assess pollution and associated health impacts.

There is no direct connection being made between poor air quality and health impacts. Air quality regulators and public health authorities are disconnected, with significant government health plans failing to identify air pollution as a cause of adverse health effects.

Emissions from transport including cars, trucks, trains and shipping

Australia’s busiest container port, the Port of Melbourne, caters for about 3,000 ships a year. The port lies adjacent to the Hobsons Bay and Maribyrnong council areas. There are also four bulk fuel import terminals along the coastline and Yarra River. The surrounding area is home to container depots with trucks using local residential streets to move the containers to and from the port. Fuel is transported from the fuel terminals by pipeline and by fuel tanker trucks, which also use local roads.

The proximity to the port and city of Melbourne and growth areas to the west and south west means that traffic in the inner west has become a significant problem. Australia has yet to adopt Euro 6 emissions rules and allows the sale of some of the dirtiest fuel of any OECD country, meaning that compliance with Euro 6 emissions limits would be unlikely.1 The Australian Truck Industry Council reports that the average age of heavy vehicles in Australia is 14.8 years, meaning that many only meet Euro 3 emissions standards and some meet none at all. Short-haul trucks ferrying containers between storage locations nearby and the port are typically older than average. Using local roads with low-speed limits, traffic lights and local traffic result in stop-start driving with plumes of black diesel exhaust from trucks a common sight, often outside schools, childcare centres, and houses. Victoria’s state government has no jurisdiction over these standards, hence our recommendation was to lobby the federal authorities to improve them.

In response to increasing traffic on local roads and congestion on the major freeway servicing the west, the Victorian state government authorised construction of a new tunnel, widening of the existing freeway and improving access to the port area from the freeway. EPA Victoria required that air quality monitoring commence 12 months before construction, during construction and for five years following opening of the tunnel. It also required the tunnel building authority to make provision for retrofitting of filtration to the two tunnel exhaust stacks if local air quality was shown to be adversely affected. The dispersion modelling indicated that the exhaust will be vented high enough above grade to ensure that ground level air quality will not be worse than prior to construction of the tunnel.

Industrial emissions including dust and odour

Of Victoria’s 39 Major Hazard Facilities (MHF) licensed by the regulator, eight (21%) are located within the reference area and a further seven in close enough proximity to have some impact on the residents. This includes a refinery, multiple fuel storage sites, bulk chemical storage (resin, herbicide), and plastic production. In addition, there is significant industry which falls outside the MHF licensing requirements but still has significant risk and impact on air quality, the health of nearby residents, and the amenity of the area. These include quarrying, concrete crushing, landfill, abattoirs and rendering, paint production, food manufacturing and bulk storage. Generation of dust is a particular issue, with unsealed roads on container storage sites and overfilled landfills significant sources. Odour is also a common complaint, with residents unable to enjoy their own gardens. Odour is generated from the rendering plant, edible oils production, landfill, bulk fuel unloading from ships, and paint manufacturing.

Many of these sites were established before residential areas surrounded them. Our acceptance of polluting industry has significantly reduced. However, conditions on planning approvals and EPA works approvals are defined at the time the activity is first planned. These define the “right to pollute” up to a point. There is no mechanism to reduce the allowable emissions or to amend the planning approval, unless the site use changes, even if the business changes ownership.

Changes to the Environment Protection Act...postponed to 2021, require businesses to take practical measures to prevent pollution occurring. Until then, EPA Victoria can only respond to pollution events after they occur

Changes to the Environment Protection Act which were due to come into effect in 2020 but were postponed to 2021, require businesses to take practical measures to prevent pollution occurring. Until then, EPA Victoria can only respond to pollution events after they occur. I consider this to be more like a safety case regime, where the operator must perform risk identification and assessments and then put mitigations in place to reduce the likelihood of pollution occurring. The concept of ALARP for control measures will also be applicable. I see this not only as a mechanism for improving air quality, but a driver for spending on engineering solutions across the state, not only in MHFs but in all types of businesses.

Communication and future activities

The CRG was required to present interim findings and a final presentation to hand over the completed report.2 When the opportunity arose, I nominated myself to attend the interim findings presentation with four state government ministers. By the time the final presentation came around in July 2020, we were all working from home due to Covid-19 restrictions, so we attended remotely. To have been given the opportunity to research the issues, prepare a report and present to state government ministers was rare, and I feel very fortunate to have been involved. Whilst we are still awaiting a formal response from the Victorian Sate Government, each of the local councils has recorded thanks in their council meetings, and one invited members to a presentation of a certificate. We have nominated ourselves for various awards and have won the Maribyrnong Council Community Strengthening Award 2020 and the Clean Air Society of Australia and New Zealand Clean Air Achievement Award 2020. The remit of the group included education of local residents about the harm that poor air quality causes and what resources are available to help them avoid the worst exposure. The completion of the report brought the formal function of the group to an end. However, the group has decided to continue the work we started by forming a new group – the Inner West Air Quality Network – to continue to lobby the government to take action on the issue of air quality. I believe that my skills in understanding some of the technical terms and methods, writing reports, and presenting information has helped me to contribute to improving serious issues in my local community. I have always been a volunteer – kindergarten committee, homebrew club, my local creek Friends group – but in this role I believe that my chemical engineering skills allow me to contribute valuable insights on the industrial and manufacturing contribution to poor air quality. I have gained a better understanding of drivers and requirements placed on polluters within the regulatory framework. I look forward to working with a passionate group of volunteers, local residents and our leaders to improve the liveability of our communities.

Further reading

1. IHS Advisory Services, 2016, Fuel Quality and Emissions Standards in Australia, retrieved from https://bit.ly/3um0yTR.

2. Inner West Air Quality Community Reference Group, 2020, Air Pollution in Melbourne’s West; Taking Direct Action to Reduce our Community’s Exposure, https://bit.ly/3vIcTCi.

To read more articles in the series visit https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/features/type/chemical-engineering-in-the-community/

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.