Maybe, You Can Drive My Car

FOR many years, hydrogen has been touted as the future for passenger cars. The hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) has zero carbon tailpipe emissions, it can be filled as quickly as a petrol equivalent and it offers a similar range to petrol between fills. Indeed, this year Toyota launched the Mirai, demonstrating its commitment to the FCEV.

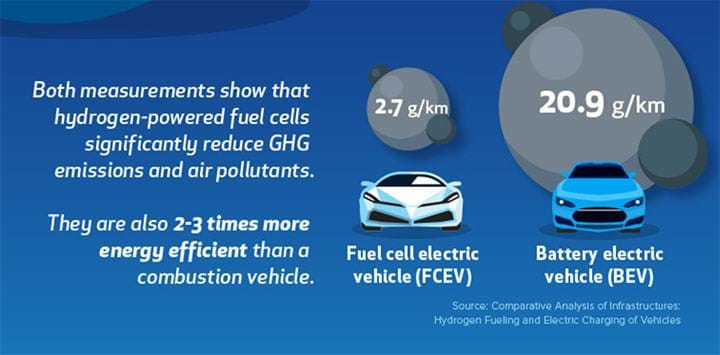

The Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association recently produced a publication outlining the case for hydrogen. Within the publication is the following graphic showing the FCEV being an order of magnitude better than the BEV with respect to carbon footprint.

A flawed concept?

So what’s not to like about the hydrogen FCEV? I think the FCEV is a flawed concept and I will explain why.

I am convinced that hydrogen has a significant role towards achieving net zero. However, the role of hydrogen in the passenger car sector is much less clear. I find it difficult to see how a hydrogen FCEV can compete with a battery electric vehicle (BEV). That conclusion was reinforced by two recent reports from BloombergNEF and Volkswagen.

BloombergNEF, Hydrogen Economy Outlook report, 30 March, 2020 concluded that “Hydrogen can play a valuable role decarbonising long-haul, heavy-payload trucks. These could be cheaper to run using hydrogen fuel cells than diesel engines by 2031. But the bulk of the car, bus and light-truck market looks set to adopt battery electric drive trains, which are a cheaper solution than fuel cells.”

Volkswagen, however, did not use high FCEV costs to support the development of the BEV – it used a fundamental energy balance to demonstrate the substantial energy efficiency benefit of a BEV over an FCEV. The BEV is twice as efficient. Volkswagen is unequivocal in its report, where the following statement is made: “The conclusion is clear: in the case of the passenger car, everything speaks in favour of the battery and practically nothing speaks in favour of hydrogen."

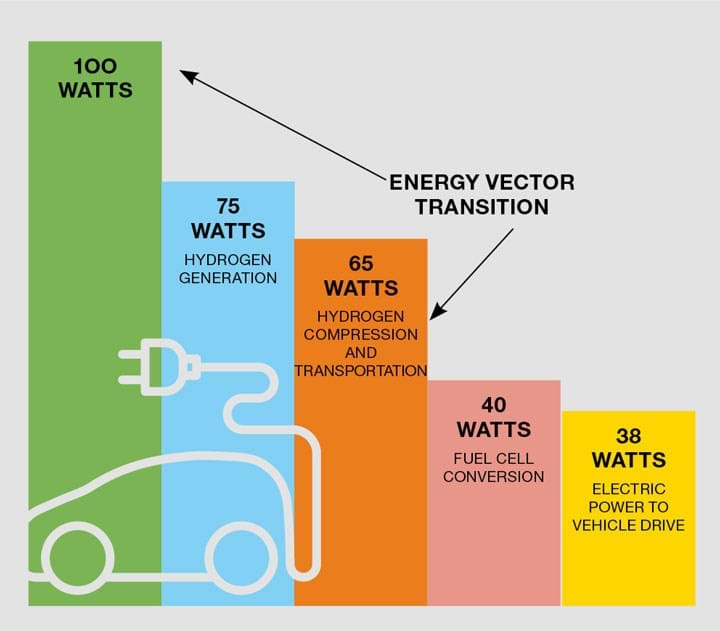

FCEVs are based upon a number of energy vector transitions – wire to gas to wire – whereas the BEV has no transition, it is wire throughout. At each vector transition there will be a substantial loss of efficiency and therein is the issue with the FCEV.

Let’s take 100 W of electricity produced by a renewable source. For the FCEV, that energy is used to produce hydrogen, possibly using electrolysis, a process that is around 75% energy efficient (steam methane reforming with CCS has a comparable efficiency). The hydrogen produced has to be compressed, chilled and transported to the hydrogen station, a process that is around 90% efficient. The hydrogen is then converted to electricity in the car fuel cell, a process that is around 60% efficient. Finally the electricity is used in a motor to provide vehicle drive, a process that is around 95% efficient. The compounding energy inefficiencies mean that only 38% of the original energy production is used to move the car. This is illustrated in the figure below.

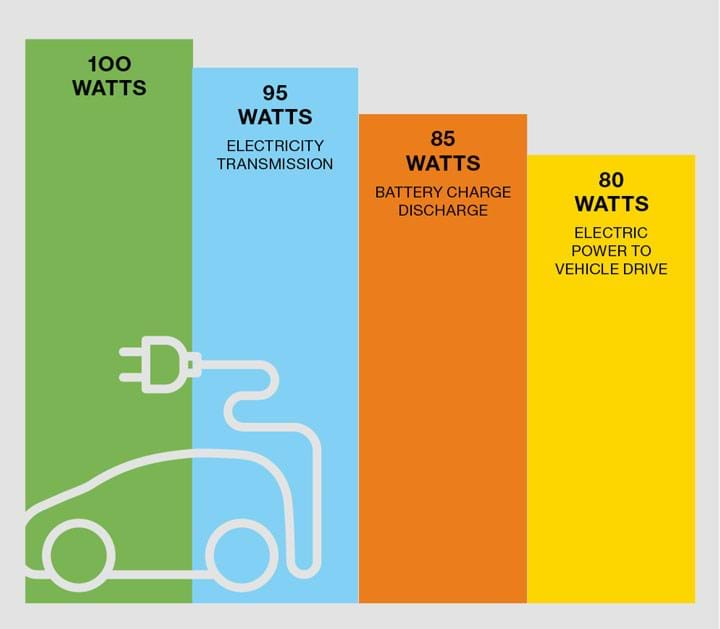

The BEV steps have no energy vector transition – it is all electric (wire). 100 W of energy is transmitted to a battery with 5% losses. Charging and discharging a lithium-ion battery results in around 10% losses and the electricity used in a motor to provide vehicle drive has a 5% loss. These steps are illustrated below.

As is evident from the figures, the FCEV requires double the energy of the BEV. This is confirmed by BMW where on reviewing the FCEV it is stated: “The overall efficiency in the power to vehicle drive energy chain is therefore only half the level of a BEV.”

It is interesting to note that there are many automotive industry reports of Mercedes halting the development of their small passenger car FCEV and will focus on large FCEV trucks in a joint venture with Volvo.

FCEV versus BEV

So why hydrogen for small vehicles? Currently the benefits are increased range and much reduced charge times. These are not insignificant benefits – like me, many people remain reluctant to purchase a BEV because of range anxiety and charge times.

We can look to China to see how range anxiety and charge times are being addressed. For example, the Battery swap concept involves drive-in forecourts where the discharged battery is automatically moved out to be replaced by a fully-charged unit, hence significantly reducing 'charge' times. NIO, the Shanghai based car manufacturer, is claiming a 3-minute swap time.

Range anxiety is being addressed through plans to build a large number of swap stations. BJEV, the electric car subsidiary of the Chinese manufacturer BAIC, is to invest €1.28bn (US$1.45bn) in the construction of 3,000 battery changing stations.

Furthermore, the battery in a BEV is a significant cost. Although model-specific, Statista reports a BEV battery to be 25% of the overall cost. By using the swap concept the battery could be rented, with part of the cost of the swap being a fee for rental. That would reduce the purchase cost of a BEV, incentivising public uptake.

Finally, the swap batteries could be charged using surplus renewable electricity – a huge environmental positive for the concept.

BEVs and the swap concept look to be a far superior option than the inefficient FCEV.

The swap concept would though require a degree of standardisation that may not be to the liking of European car manufacturers.

Bias

Returning to the Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association stating that the carbon emissions were an order of magnitude better for a FCEV, I suspected a bias in this claim. I therefore went to the source – Comparative Analysis of Infrastructure Hydrogen Fuelling and Electric Charging of Vehicle, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Institut für Energie- und Klimaforschung – Elektrochemische Verfahrenstechnik.

On reviewing the report the bias became obvious: the hydrogen for the FCEV is provided by carbon-free renewables, whereas the energy for the BEV is from burning fossil fuels. If the authors assumed that batteries could also be charged from renewables the carbon footprint for BEV and FCEV would be similar. The graphic also presents the FCEV being 2–3 times more efficient than an internal combustion engine. What it doesn’t say is that the FCEV is 2–3 times less efficient than a BEV.

Who funded the Institut für Energie report? It was H2 Mobility.

Adapted from an article first published by the author, on The Conversation.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.