How to be a Good Mentee

IT IS no coincidence that the most successful people in the world have had mentors. Mark Zuckerberg, CEO and co-founder of Facebook was mentored by Steve Jobs. Bill Gates of Microsoft was mentored by Warren Buffett. Sir Richard Branson was mentored by Freddie Laker. Mentoring helps people succeed – whether that’s succeeding at a global business level, or at a more modest level achieving CEng status, or a better work-life balance.

When considering mentoring, we tend to focus more on the skills of the mentor, and for good reason. Poor mentoring can inhibit people succeeding. I reviewed good mentoring practice in a previous issue of The Chemical Engineer1. However, now I want to focus on the role of the mentee in the mentoring relationship. I will look at the benefits of having a mentor, selecting a mentor, and getting the best from them.

As you read this, I expect you fit at least one of the following categories: (1) You already have a mentor; (2) you don’t have a mentor but would like one; (3) you don’t have a mentor and wouldn’t like one; (4) you are a mentor.

If you are a category 1 person, you might be interested in getting the best out of your mentor. If you are a category 2 person, you might also be interested in how to select a mentor. If you are a category 3 person, please consider Richard Branson’s perspective on mentoring avoidance: “going it alone is an admirable but foolhardy and highly-flawed approach to taking on the world.”

Category 4 people are those who are already mentors or who are considering it. First off, existing mentors are also likely to benefit from the section on getting the best from your mentor. Secondly, if you are a mentor, it is good practice to be a mentee as well. In other words, find yourself someone to mentor you. This creates balance and avoids you becoming drained, particularly if you have more than one mentee.

What is mentoring?

In the most general sense, mentoring is a relationship in which one person (the mentor) facilitates the professional development of another person (the mentee). This may be related to career planning and progression, acquiring new skills or qualifications, managing transitions, or generally performing better. Usually the mentor has relevant experience that they can draw upon, and here lies the big challenge in mentoring. There is a natural inclination for mentors to give advice, and for mentees to seek advice. This is usually not helpful. Giving and receiving advice creates dependency, and stifles development. Furthermore, there is an assumption that the advisor knows the full situation, and this is rarely the case. The trick in effective mentoring is for the mentor to combine their experience with core facilitative skills to help the mentee develop independently.

A mentor helps us to identify what we want, and then encourages us to achieve it. This might be something relatively small, or something quite major

In practical terms, mentoring involves a series of meetings between the mentor and mentee, to discuss the mentee’s professional development. There may be a clear goal and time limit for the relationship, eg in the case of the mentee, achieving CEng status. Alternatively there may be no clear goal or time limit. The relationship may be established formally through the mentee’s organisation, or it may be informally established through personal contacts. In fact, the relationship might be so informal that neither party refers to it as mentoring; it’s just one experienced person guiding a less experienced person through the minefield of professional life. I can think of key individuals who have guided me in this way when I was starting out, and I can look back and reflect on how I could have got more out of those relationships. It is with this hindsight that I write this article.

Benefits of mentoring

Having a mentor has been likened to stepping on one of those moving walkways you find at airports, propelling you on your baggage-laden journey. Let’s examine these benefits in more detail.

A mentor helps us to identify what we want, and then encourages us to achieve it. This might be something relatively small, or something quite major. We can consider these achievements to be the main, or explicit, benefit of the mentoring relationship. In addition to these, there are other, implicit benefits that relate to personal growth. For example, the mentee might grow in confidence, independence, motivation, and responsibility. They might pick up skills in areas such as planning and prioritising, communication and creative thinking.

It is worth remembering that mentors can also derive benefit from the mentoring relationship. For example, a discussion about prioritising work will not only benefit the mentee; it will give the mentor an opportunity to reflect on their own approach to prioritisation. The benefit to the mentee and mentor propagates outward to their organisations, reflecting in better performance, and increased staff retention.

Selecting a mentor

Let’s say you like the idea of having a mentor. How do you go about getting the right one? The quest for the right mentor begins with asking yourself the following questions: What do I want to achieve from the mentoring relationship? What’s my personality, character, or social style? How do I learn best?

These questions may only take a few minutes to answer, and the answers should prove valuable.

What do you want to achieve from the mentoring relationship? It is important to be clear about goals and aspirations. Is your goal specific? For example, becoming Chartered, or moving into a new field? Alternatively, you might aspire to being more effective in your present role. It is important to be clear with yourself about what you want. This will help you to select a mentor with relevant experience. It may be that you are looking for some sort of change, but don’t know what you want. This is perfectly okay. I suspect that none of us knows what we want all of the time. If you are in a transitional state, then perhaps the one thing you might want to achieve from the mentoring relationship is clarity.

What’s your personality, character or social style? An awareness of your personality traits in relating to others is useful because it will help you match your style to the style of your mentor. If for example you have a quiet and reflective nature, you might not want a mentor who is naturally loud and spontaneous. On the other hand, this might be exactly the kind of mentor you are seeking.

An awareness of your personality traits in relating to others is useful because it will help you match your style to the style of your mentor. If for example you have a quiet and reflective nature, you might not want a mentor who is naturally loud and spontaneous

There are many approaches to describing personality or character. You may have encountered the Myers-Briggs Type Index2 (MBTI), DISC, or Social Styles3 approaches; all very interesting stuff. However, to answer this question you do not need to sign up for a detailed character assessment. Just spend a few minutes to write down a few adjectives that describe how you conduct yourself, eg reserved or outgoing, intuitive or logical, spontaneous or considered, direct or indirect. You might benefit from asking a trusted colleague how they might describe you. Others see us as we really are. We can’t see ourselves as we are on the inside looking out.

Once we have got a feel for our style, we can think of how that might work for us, or against us, in our mentoring relationship, and what sort of style might we be looking for in our mentor. Now, we cannot use this as a criterion for mentor selection like we were filtering CVs for job applicants. First, mentors do not usually come with up-front character descriptions. Secondly, the match between mentor and mentee involves a complex and dynamic interplay of factors that cannot be predicted. Thirdly, it is likely that we are selecting from a field of one or two potential mentors. The great benefit in thinking about our style is that it gives us ammunition for the initial scoping conversation with a potential mentor.

How do I learn best?

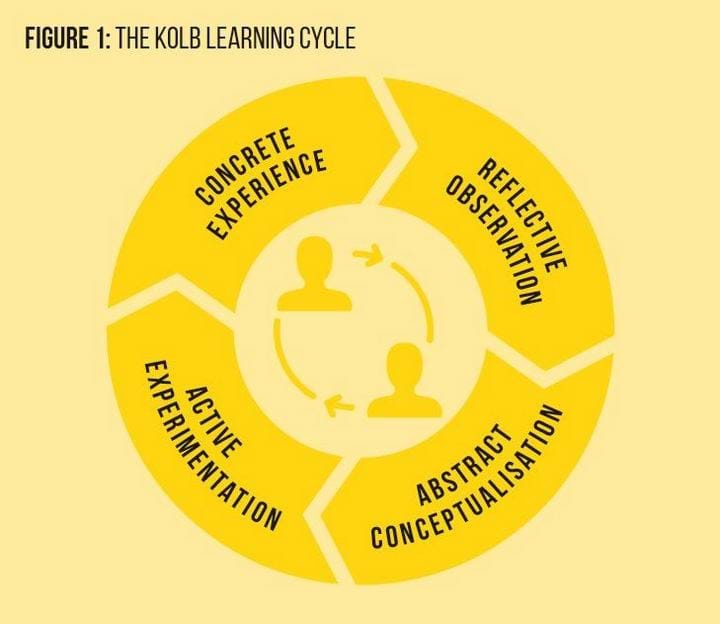

Being mentored involves learning, whether it’s new skills, new ways of thinking, or learning about ourselves. Learning involves a sequence of activities, expressed succinctly by the work of Kolb4 in his well-established learning cycle (see Figure 1).

The Kolb learning cycle

The Kolb learning cycle works like this. Say you want to learn some creative problem-solving techniques. This desire is likely to be borne out of some concrete experience which revealed the shortcomings in your traditional problem-solving approach. A discussion with your mentor leads to some reflective observation which reveals the need for a different approach. Your mentor then introduces you to some lateral thinking techniques5 in the abstract conceptualisation phase. In isolation these are meaningless, but by active experimentation you have a chance to test the lateral thinking techniques. This leads to more experience, more observation, more concepts and more experimentation. Before long you become an established and successful practitioner of lateral thinking techniques.

The Kolb learning cycle is useful in mentoring because understanding how we learn can help the process. It also gives us a common language to discuss the process with our mentor. The cycle also reveals different learning styles. We naturally tend to be more comfortable in one of the phases of the cycle. If we are a theorist for example, we are comfortable in the abstract conceptualisation phase, but we might need a bit of a push from our mentor to get round the complete cycle. Discussing your preferred learning style with your mentor at the kick-off meeting would be a good plan, as well as checking to see that there is a good match. If you are both theorists you might get on very well with each other, but the learning experience might not be so rich.

We have spent some time looking at three useful questions you should ask yourself before you track down a mentor. They will help you in the initial conversations to see if there is potentially a good match. Of course there are several practical issues that need to be considered when choosing a mentor, such as availability, confidentiality, conflicts of interest and ethics. Relevant issues such as these should be addressed in a mentoring agreement. This was discussed in my earlier article on mentoring.

Discussing your preferred learning style with your mentor at the kick-off meeting would be a good plan, as well as checking to see that there is a good match

Before we move on to talk about getting the best from your mentor, imagine the following scenario. You’ve identified the perfect person to mentor you. They have just the right experience, and you have already established some mutual respect. What’s going to be their likely response if you turn to them one day and say: “Hey, how about being my mentor?” It’s probably not going to go well. The word “mentor” might suggest to them another administrative burden that they could do without. Alternatively, they might come back at you with: “Oh no... I’m not possibly good enough, or qualified enough.” You are likely to get a better result if you just say something like: “Do you have time for a chat later this week? I’d love to get your perspective on what I might do to get better at…” After a few meetings like this you might have established a mentoring relationship between you without actually using the M-word.

Getting the best from your mentor

Assuming you have been fortunate enough to find yourself a mentor, let’s look at what you can do to get the best from the mentoring relationship.

Expectations

It will help greatly if you have realistic expectations. The mentor’s role is to facilitate, not to fix problems. You can expect their undivided attention during meetings, and to follow through on any specific action points against their name. For example, they might offer to forward you a useful document or contact details. Do not expect them to tell you what to do, to chase you up, to get you promoted, or give you an easy time. It would be appropriate to discuss expectations at the outset of the mentoring relationship, and to review them as required.

Responsibility

The lines of responsibility should be clearly defined. The mentor has responsibility for managing the mentoring process, normally in consultation with the mentee. The mentee has responsibility for setting the agenda, normally in consultation with the mentor. Joint responsibility is taken for the outcomes of the relationship. Having these responsibilities clear at the start can avoid confusion and frustration.

Strategy

Having a strategy for your future will really give focus to the mentoring. Start to make plans for the next few weeks, few months and few years, and use your mentor as a sounding board to give you a sense check. If you don’t have a strategy, use the mentoring sessions to help you develop one. It’s a scary thought that if you don’t take control of your life, then the important decisions about your future will be effectively dictated to you by circumstances.

Proactivity

Remember that the mentoring relationship exists to help you. If you are passive and disengaged, you will not reap the benefits. Your mentor might try to encourage you, but will not chase you or nag you. However, if you are proactive and engaged in the process, your mentor should respond positively. You can be proactive by preparing for each meeting with your mentor, deciding what you want to achieve, and engaging in regular reviews of progress.

Reflection

We saw earlier that the Kolb learning cycle involves reflective observation. This is a necessary part of learning and growing, but some people find it difficult. For example, your mentor might ask you what you could have done differently in a given situation. Suddenly you are in the reflection spotlight. Some people seize up and can’t think – frightened by the potential silence they make a joke or say the first thing that comes into their head. It is going to help you and your mentor if you can get comfortable with the process of reflection. Your mentor should encourage you and not pressurise you.

Imagination

Often the solutions to complex problems require some imagination. Let’s say for example you go to your mentor with the feeling that you want to change your job role, but there are many complicating factors. Your mentor might ask you to imagine and describe your ideal situation at some time in the future. This is a very powerful approach that enables exploration of future scenarios and consequences of decisions. However, it does require you to engage your imagination. Being comfortable with blue sky thinking and exploring “what-if” scenarios should have a positive impact on the mentoring process.

We have considered a few factors that will help you get the best out of your mentor. To close let’s list some top tips aimed to help mentees.

Top tips for mentees

- Be appreciative. Don’t take your mentor for granted.

- Recognise that change is down to you, not your mentor.

- Prepare well for meetings, do your homework, and be punctual.

- Discuss expectations.

- Be committed to the process. There is a strong correlation between what you put in and what you get out of the relationship.

- If something is not working, discuss it with your mentor.

- Respect the boundaries of the mentoring remit.

- Don’t try to become like your mentor. Try to become a better version of yourself.

- Don’t take things personally.

- Be aware of the spin-off learning, eg communication skills.

Finally, now you are equipped to engage as effective mentees, I strongly encourage you to give back what you have received by becoming effective mentors to someone else. I firmly believe that any organisation that has a strong mentoring culture will be more productive and a happier place.

Further reading

1. Cleaver, JAS, “How to mentor”, The Chemical Engineer, Feb 2016, p44.

2. Briggs-Myers, I, Myers, PB, Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type, Davies-Black Publishing, 1995.

3. Merrill, DW and Reid, RH, Personal styles and effective performance, CRC Press, 1999.

4. Kolb, DA, Experiential learning, Pearson Educational Publishing, 2015.

5. de Bono, E, Lateral thinking, a textbook of creativity, Penguin, London, 2009.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.