How to Mentor

Mentors and mentees alike need to understand what good practice looks like, as the results of getting it wrong can be damaging

PERHAPS you are new to the idea of mentoring, maybe you are a seasoned mentor, or you might be a potential mentee looking for a mentor. Whether you are part of a formal mentoring programme, or just curious about the prospect of informal mentoring, being aware of a few simple principles can bring great benefits.

Mentoring is a growing activity. Companies and institutions are establishing mentoring schemes, as mentoring becomes recognised for its positive potential. It therefore makes sense to consider how to be a good mentor – not just to raise your game, but because there is potential to do damage if you get it wrong. In other words, a poor mentor, even with good intentions, can demotivate, undermine self-confidence, and promote dependence, rather than independence. It’s worthwhile knowing what good mentoring practice is.

What is mentoring?

The essence of mentoring is about helping people to help themselves. The mentor should be in a position to help, by offering experience, wisdom or fresh perspectives. Mentees ‘helping themselves’ implies that responsibility for progress lies with the mentee. This is a very important point that we shall return to shortly. The context usually relates to professional development, and the framework takes the form of a mutually-agreed mentoring relationship. This relationship might be part of a formal company scheme, or it might be an informal arrangement between colleagues. It might be internal, involving a mentor and mentee from the same organisation, or it might be external, where the mentor might be from outside the mentee’s organisation.

So is mentoring the same as coaching? Some people use the terms interchangeably, and there is certainly some overlap. The main distinctions are summarised in Table 1. The key difference for our purposes is that mentoring implies a more long-term, or open-ended relationship in which the mentor can draw on their knowledge or experience of the field to help the mentee. Coaching is often short-term, with a specific focus. The coach does not necessarily require relevant or specialised knowledge of the field, but relies on coaching skills to get results. Effective mentoring therefore involves combining knowledge and experience, coupled with proficient coaching skills. We will say more about coaching skills shortly.

The benefits of good mentoring are far-reaching. The positive impact on the mentee’s professional development is explicit, whether it is guidance in getting Chartered, help with stepping into a new role, or identifying and acquiring new skills. However, there are also considerable benefits to the organisation and to the mentor. Organisational benefits of mentoring follow logically in terms of increased staff motivation, productivity and creativity; better staff recruitment and retention; and reduced stress, grievances, and absenteeism.

The positive feature of organisational benefits of mentoring is that they can be quantified. But what’s in it for the mentor? Well, apart from the great satisfaction that comes from helping others, mentoring adds value to the mentor too. It introduces you to new perspectives, encourages you to reflect on your own professional development, and sharpens your interpersonal skills.

Wouldn’t it be good to have a ten-point checklist procedure or approach for effective mentoring that we can apply, like we would in design or fault-finding? Mentoring approaches exist, but like any tool, they require skilled use. The challenge in using these tools arises because mentoring is dynamic and unpredictable, and every mentoring relationship is unique. Proficient use of mentoring tools comes with training and learning by experience.

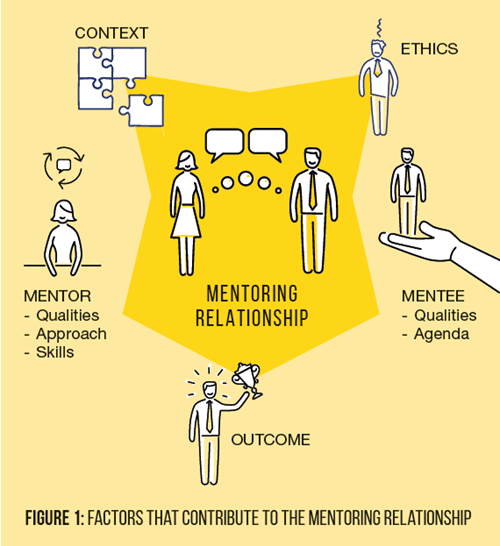

So what’s involved in mentoring? At the heart of mentoring is the mentoring relationship, in which the qualities and skills of the mentor are only a part of the picture (see Figure 1).

To be effective, we need to tune in to the other factors that contribute to the relationship before we focus specifically on the attributes of the mentor.

The context

This relates to systemic factors that influence and frame the mentoring relationship. Typical factors include the nature of the working environment, any formal mentoring remit, and specific challenges such as getting Chartered. These factors are usually fixed, and therefore the mentor has to be aware of them and work with them, or around them.

Ethics

An effective mentoring relationship is built on a platform for developing trust. This platform is guided by ethics surrounding issues such as confidentiality, fairness and autonomy. At the start of a mentoring relationship, these issues should be discussed, agreed, and formalised if necessary, in a working agreement. The mentor’s role is to initiate this discussion.

The mentee

It’s important to appreciate that the other partner in the mentoring relationship will have a unique starting point, and will show up with varying levels of commitment, clarity, confidence and independence. This feedstock variability creates a huge challenge for the mentor, who must be sufficiently perceptive and flexible to adapt to the mentee, and help them clarify their agenda and targets.

Outcome

The tangible outcome of mentoring can be valued by the extent of action taken and changes made, when compared against the mentee’s initial goals or objectives. However, there are likely to be intangible outcomes that are difficult to measure. These might relate to increased confidence and wellbeing, or clarity and assurance that comes from discussing options. It is important for the mentor to encourage the mentee to reflect on the tangible and intangible outcomes of the mentoring relationship.

The mentor

Expanding on our original concept of helping people to help themselves, the mentor’s role is to facilitate learning and development in a supportive and challenging manner. This is easier said than done, and requires a combination of qualities and skills along with a suitable approach. Let’s briefly get to grips with these concepts before expanding on mentoring skills and approaches.

Mentor qualities

These are individual attributes such as style, personality, experience and wisdom. An effective mentor would be aware of their qualities and deploy those that would enhance the mentoring relationship, and withhold those that will detract or distract. For example, a mentor with relevant practical experience might share it with the mentee in an anecdotal way. The use of mentor qualities in the relationship is one of the main distinctions between mentoring and coaching.

Mentor skills

We can distinguish between core skills and practical skills. Core skills are based around effective communication, and are essential in order for the mentor to connect and build a rapport with the mentee. These skills take a lifetime to learn. Practical skills on the other hand, relate to various tools and techniques that the mentor can deploy to facilitate the mentoring process. They are easily learned, or may be already familiar to you. A tool like SWOT analysis for example, is familiar to many. However, the real skill comes in using the right tool at the right time, and in being able to make sense of the outcome, so you can suggest what tool to use next. We will cover some useful tools towards the end of the article.

Mentoring approach

This is a structure, framework or philosophy that guides the mentoring process. A number of approaches are available, each with various features and merits. Some of the commonly-encountered approaches are listed in Table 2. Becoming proficient in any of these approaches takes time, training, and practice. Even professional coaches might only master two or maybe three approaches. However, anyone new to mentoring can be effective, even with a basic awareness of a mentoring approach. Probably the most accessible and relevant approach for mentoring is Egan’s Skilled Helper Model. More on this later.

Core skills for mentoring

So far, we have examined the concepts behind mentoring, and considered the various factors that are involved. It’s now time to examine in depth the core skills required when we are face-to-face with a mentee. These skills enable us to establish a rapport quickly, to put the mentee at ease, and to know when to push and challenge the mentee, and when to support and encourage. Let’s be clear, we cannot obtain these skills by reading. They are acquired by experience.

A good place to start is with Carl Rogers, the founder of modern coaching and mentoring practice. He identified the three core conditions of empathy, authenticity, and respect that contribute to effective mentoring and coaching.

Empathy is the ability to put ourselves into the mental shoes of another person, to understand their emotions, feelings, and expectations. This concept underpins all communication, and is particularly vital in mentoring. If we are not aware of the emotions of our mentee, we are going to get an incomplete picture of the situation, our input is likely to be insensitive, and the mentee is not going to feel valued and respected. We can develop our ability to empathise by careful listening and using body language. Using these principles, a good mentor will be able to pick up subtle changes in the mentee’s emotional state. We will explore listening and body language in more detail below.

Authenticity involves being your genuine self, and is important as it allows trust to develop. It can also help to defeat negative attitudes. A warm and genuine approach allows the mentee to feel valued, which in turn builds self-esteem. Having a sincere interest in the development of your mentee has great power. Faking a sincere interest is transparent and leads to a lack of trust and an ineffective mentoring relationship.

Respect, or unconditional positive regard is about valuing people as themselves. Rogers considered that this was an important requirement to enable people to grow and fulfil their potential. The mentor may not approve of the mentee’s actions, values, or decisions, but they should maintain an attitude of respect and acceptance regarding the mentee.

Having at least an awareness of Rogers' core conditions should help you take your first steps in the right direction as a mentor. Part of your development as a mentor should involve growing in authenticity, respect, and in your ability to empathise using careful listening and fluency in body language. The latter two skills can be readily developed.

Listening

Most people would claim to be good listeners. Ask yourself when was the last time you really focussed on what someone was saying, trying to understand them completely, without interrupting. Now ask yourself the reverse question; when was the last time someone listened to you in this way, giving their undivided attention, really seeking to understand. The answer to both questions for most people is “never”. This level of focussed listening is what is required for effective mentoring. It has two immediate benefits. First, the mentor gets the full information, including facts and feelings, and so is able to empathise. Secondly, the very act of listening carefully to someone makes them feel valued, un-rushed, and promotes creative thought. This is why sometimes listening attentively to someone can help them solve a problem. It’s also a very powerful way of building trust in a relationship.

The challenge to attentive listening, particularly for engineers, is that we tend towards diagnostic listening. We focus on the facts, and our mind is already working on trouble-shooting and problem solving. Immediately our attention is not on the speaker, and we are missing valuable information. A mentor needs to steer away from this natural problem-solving tendency, and listen to the person. Remember, we are trying to help people to help themselves. We can do this best by soaking up everything they say, and perhaps reflecting it back to them to make sure we understand them.

The other potential challenge to attentive listening for a mentor is that we have to suspend our own agenda. This goes against the grain because we are accustomed to competing to get our ideas heard and our solutions adopted. Usually in a meeting, we are on the lookout for occasions to shine, to show our knowledge. This approach has no place in effective mentoring. First, it means we are not fully listening to the mentee if we are focussing on ourselves. Secondly, and more fundamentally, we are missing the point that mentoring is about helping other people, and not helping ourselves.

Body language

We communicate our emotions and feelings through body language. Having at least an awareness of body language helps us in everyday communication, whether we are speaking to senior staff, colleagues, or junior staff. Body language is particularly important for mentors because, when coupled with attentive listening, it helps us to empathise. Most of us have an awareness of body language through differences in facial expression and posture. A good mentor builds on this by developing an awareness of the dynamics, noticing subtle body language changes that might suggest a positive or negative response to an idea, for example. A good mentor also uses their own body language to put the mentee at ease and to help build a rapport. Body language fluency is something that can be developed, just by being aware of it. A note of caution however: people from different cultural backgrounds use different body language and this can cause confusion and misunderstanding.

The skilled helper model

Now we have examined the core skills required for mentoring, let’s take a look in detail at one of the more accessible and relevant mentoring approaches. Egan’s skilled helper model4 is an ideal framework for mentoring, and is widely used. It is disarmingly simple, being based on just three stages or questions:

1. What’s going on? (the current picture)

2. What do you want instead? (the preferred picture)

3. How might you get what you want? (the way forward)

Each stage involves three steps that help to answer the question fully. The model is easily represented by the simple matrix shown in Figure 2.

We make progress through the model by moving from left to right, enabling the mentee to take appropriate action that leads to valued outcomes. Notice that we might jump back and forth between the steps in each stage as required, to gain clarity or to explore ideas further.

Stage 1 is about clarifying the issues that are driving the desire to change. In the first step, the mentor builds rapport, and encourages the mentee to describe the current situation. The second step is about ensuring that the mentee does not overlook any perspectives, and challenges any assumptions that might be restricting. The third step encourages the mentee to summarise the whole picture, to focus on the most important issues, and to prioritise what to work on.

Stage 2 is about encouraging the mentee to focus on the preferred picture; to imagine possible ways forward, to set some goals or objectives, and to check that the goals are appropriate. In step 1, we adopt classical creative thinking by suspending judgement and generating as many ideas as possible. In step 2, we take our ideas and set an agenda for change. In step 3, we get the mentee to test their commitment and motivation for change.

Stage 3 is about planning a way forward. In step 1, again we think creatively about the various ways in which the mentee could achieve their goal. In step 2, we help the mentee to discover the most suitable strategy for them. In step 3, we encourage the mentee to draw up a plan for action.

Applying the skilled helper model

We have already indicated that the skilled helper model is non-linear and iterative. It is important to remember that the mentoring process should start wherever the mentee is, and follow their agenda. Your mentee might show up requiring step 1 of stage 1 to help them identify what’s going on. They might show up very clear on what they are about, and just need step 3 of stage 3 to help them plan their next move. However, they are most likely to show up somewhere in between these two states. The experienced practitioner of the skilled helper model will be able to locate quickly the mentee’s position in the matrix and be able to chart a way forwards. Depending on the situation, some stages or steps of the model may require no discussion; others may take several sessions to explore. A certain amount of iteration may occur, within a stage, or between stages. The model merely provides a guiding framework with points of reference.

Potential problems

To complete these ideas on mentoring, let’s take a look at some potential problems and collect some thoughts on how to overcome them.

The reluctant mentee

Sometimes mentees might be assigned to a mentor automatically, or assigned with the intention of rectifying perceived problems such as poor performance. In these cases, the mentee might be reluctant to engage with the process. This is a real challenge. It is useful to start from the viewpoint that people can change if they choose to, and help them to discover the benefits of having a mentor. Rogers’ core skills of empathy, respect, and genuineness are essential here. Don’t take it personally. Be there for them and be prepared to help when they are ready for it, on your terms as well as theirs.

The broken mentoring relationship

At times, the mentor may feel that the relationship is not working. Perhaps they have to put in too much effort, perhaps they are out of their depth with the nature of the challenges, or perhaps there is a clash of ideologies or values. Alternatively, the mentee may feel over-challenged or under-challenged, or perhaps the adopted approach is too structured or not sufficiently structured. Maybe they just feel that the mentor is not sufficiently on their wavelength.

Review meetings are a good way of identifying problems. Mentors can raise their concerns in a non-judgemental way and work towards a solution jointly with the mentee. Useful questions that explore the mentee’s view might be: What am I doing that is helping you? What am I doing that is getting in the way? If there was something you would like to change about the way we work, what would it be?

The temptation to give advice

Giving advice is not recognised as one of the skills or qualities of effective mentors. However, there is often great temptation to offer advice to the mentee, especially given the level of professional experience and knowledge of the mentor. Beware of giving advice for the following reasons:

- Only the mentee knows what is best for them.

- It can create dependence and reduce the resourcefulness and autonomy of the mentee.

- It rarely works, as people often don’t take advice.

When asked or tempted to give advice, we could:

- Try to facilitate the mentee to advise themselves.

- Provide facts and information that might be useful to them.

- Perhaps share our own experiences, with the caveat that our situation will be different from their own.

The mentor/manager

Can a mentor be the mentee’s manager? This represents a potential conflict of interests if the mentor/manager were to confuse the roles. It would be difficult to make unbiased management decisions, appraisals or assessments. The mentee may feel reluctant to discuss areas of weakness or dissatisfaction with the mentor/manager. Ethical considerations must play a big part in defining the working agreement.

Some mentees would naturally choose their manager as their mentor due to their respect for their experience or integrity. In this case there is a tendency for the learning relationship to be more skill-based, rather than based on behaviour.

The mentor/friend

Can you be a mentor to a friend? This is really about setting clear boundaries and flagging up when you are in the mentor/mentee role. It is therefore important that the mentoring meetings occur in a set location at a set time and for a set duration. Some people may be able to flip easily between the roles of mentor/mentee and friends; others may struggle with the split. It is probably an issue that is worthwhile discussing. Remember also that as a mentor you have a life-long responsibility to the mentee regarding confidentiality, and this needs guarding carefully to preserve the trust, long after you have moved on from the mentoring relationship.

A mentor, not a counsellor

Occasionally a mentee might have psychological issues, perhaps relating to illness, bereavement, or relationships, for example. This is way beyond the remit of mentoring. Do not just “have a go” at helping them, first because you can do real damage to the mentee’s wellbeing, and secondly the burden may well have a negative impact on you.

Suggest to your mentee that they seek the right kind of support from a trained counsellor. This type of situation emphasises the importance of establishing a mentoring agreement to define the boundaries of the discussions.

Reaping rewards

Helping others to help themselves can be really rewarding for all involved. I hope this has inspired you to consider mentoring, and has given you some guidance on how to get started in mentoring or how you might raise your mentoring game. Remember that mentoring is learned through experience, and by self-reflection. It’s constructive to ask your mentee for feedback to help you improve. As a final thought, the single most important quality a mentor can exhibit is a genuine interest in the welfare and success of the mentee. If this isn’t in place, the success of the mentoring relationship will be mediocre at best.

References

1. Connor, M and Pokora, J, Coaching and Mentoring at Work, 2nd edition, Open University Press, McGraw-Hill, England, 2012.

2. Whitworth, L, Kimsey-House, H, and Sandahl, P, Co-active Coaching: New skills for Coaching People Toward Success in Work and Life, Mountain View, CA, US, Davies Black, 1998.

3. Pask, R and Joy, B, Mentoring-coaching: A Guide for Education Professionals, Maidenhead, Open University Press, 2007.

4. Egan, G, The Skilled Helper, 9th Edition, Belmont, CA, US, Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning, 2010.

5. Jackson, PZ, The Solutions Focus, London, Nicholas Brealey, 2002.

6. Lapworth, P and Sills, C, An Introduction to Transactional Analysis, Sage Publications, London 2011.

7. Bluckert, P, “The Gestalt Approach to Coaching”, in Cox, E, Bachkirova, T and Clutterbuck, D (eds), The complete Handbook of Coaching, Sage, London 2010.

8. Whitmore, J, Coaching for Performance: GROWing People, Performance and Purpose, 3rd edition, Nicholas Brealey, London 2010

9. Gallwey, T, The Inner Game of Work, Orion, London, 2000.

10. Downey, M, Effective Coaching: Lessons from the Coaches’ Coach, 2nd edition, Texere, London, 2003.

11. Grimley, B, "The NLP Approach to Coaching," in Cox, E, Bachkirova, T and Clutterbuck, D (eds), The complete Handbook of Coaching, Sage, London 2010.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.