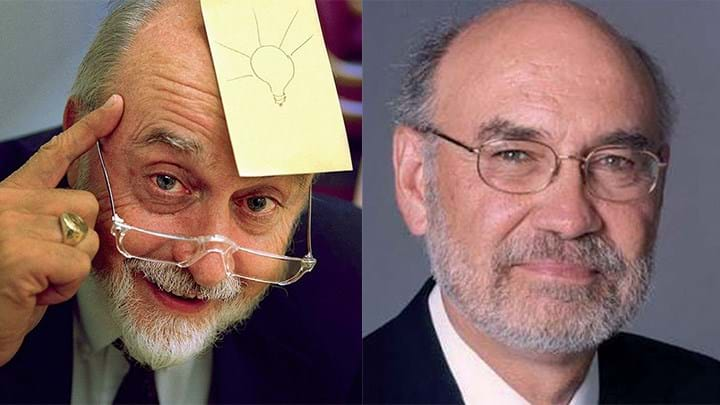

Spencer Silver and Arthur Fry – In Search Of An Application

Spencer Silver and Arthur Fry: the chemist and the tinkerer who created the Post-it Note

IT’S not enough to have a great new invention, you need to have the right application, too. No invention illustrates this better than the humble Post-it Note.

Ubiquitous in offices around the world today (and probably most homes too), the Post-it Note took well over a decade to develop because while innovators knew they had a very unusual adhesive, it took them years to find the right application, and longer still to convince the management of the product’s potential.

Today, it’s one of the best known products of 3M, a company famed for fostering innovation. While it did not make its inventors rich, their work has been recognised by their company and their peers.

A unique adhesive

The story of the Post-it Note begins in 1968 with Spencer Silver, a senior chemist who joined 3M’s central research laboratories during the mid-60s.

Silver was part of a five-strong team working on pressure-sensitive adhesives, who’d been tasked with developing stronger acrylate copolymer-based adhesives for the aerospace industry.

In an interview published in the Financial Times in 2010, he recounted the experiment that resulted in an unusual adhesive: “I added more than the recommended amount of the chemical reactant that causes the molecules to polymerise. The result was quite astonishing. Instead of dissolving, the small particles that were produced dispersed in solvents. That was really novel and I began experimenting further.”

Further investigation showed that the microspheres that were formed in his experiment stopped the adhesive from bonding firmly – it’s been likened to ‘sticking to a bunch of marbles’. This results in an unusual combination of high tack, or stickiness, with low peel adhesion (a measure of how easily an adhesive can be removed from a surface it’s been stuck to).

In search of an application

The adhesive was unique, and Silver was convinced that it had potential. But potential for what, that was the question – it certainly was no good for gluing aeroplanes together, which had been Silver’s original task. Silver experimentally coated a bulletin board with the adhesive, effectively creating a pinless pinboard. But further applications were not forthcoming. The strange adhesive was quite literally stuck on the drawing board, and Silver was reassigned to other projects.

In frustration, he started using 3M’s technical forums to tell other employees about his unusual product, in the hope that this may spark an idea and an application in another department.

Divine inspiration

One of the people attending Silver’s seminars was Arthur Fry. Fry has been described as “a tinkerer and a problem solver” who already in childhood loved to build things, almost as much as he loved taking them apart. His father, exasperated with Fry’s destructive inquisitiveness, resorted to taking his son to the rubbish tip to find new objects to satisfy his curiosity.

Inspired by a family full of engineers and an outstanding chemistry teacher, Fry went on to study chemical engineering at the University of Minnesota during the 1950s. He joined 3M’s new product development team even before he had graduated.

Fry worked in 3M’s tape division, which housed some of 3M’s most important products to date, Scotch Magic Tape and masking tape. In his spare time, he sang in a local church choir. It was there, on a Sunday in 1973, that he had an inspiration that would eventually culminate in the Post-It Note.

Fry’s problem was the bookmark he used during choir practice was slippery and tended to fall out, causing him to lose his place. “Everybody was singing while I was trying to find which page we were on. I was thinking ‘I wish I had a bookmark that would stick to the paper but that couldn’t pull it apart’,” he remembered in an interview he recorded for the Smithsonian Institution.

More pre-occupied with his problem than the sermon, Fry remembered Silver’s adhesive. “That’s when I thought about the microspheres. I realised that if they push close together they’ll be stickier, if they’re spread apart they’ll be less sticky – I should be able to find some magic spacing where it’ll be just right for paper.”

The very next day, he obtained a sample and tried it; he could legitimately do this during work time because 3M encourages innovation by allowing employees to use 15% of their time to follow up research of their own choosing.

The result was promising – the bookmark stuck, but could be removed without damaging the pages. After a bit of tinkering Fry had adjusted the formulation till it had just the right balance of tackiness and peel adhesion for paper.

From bookmark to notepad

Was this to be the application that would sell Silver’s strange adhesive? A non-slip bookmark? Not exactly. The real breakthrough happened some time later, quite by accident.

“One day, I was writing a report and I cut out a bit of bookmark, wrote a question on it and stuck it on the front,” Fry said in another interview. “My supervisor wrote his answer on the same paper, stuck it back on the front, and returned it to me. It was a eureka, head-flapping moment – I can still feel the excitement. I had my product: a sticky note.”

Selling an idea

Even so, the sticky notes were not an overnight success. 3M’s management had serious doubts over the product’s potential, and market research concluded that the sales and customer base were very limited.

Fry challenged the market research. He started distributing Post-it Notes internally in 3M, and kept a log of their use. “The data said that […] people were using 7–20 pads per year. During the same time they’d only get through one roll of Magic Tape – yet Magic Tape was the cash cow that was supporting the work on Post-it Notes.”

When a manager doubted the Post-it Notes’ potential, the manager’s secretary was given a palette of them and asked to keep track of their distribution. “Two weeks later she was on her second pallet and the manager changed his opinion,” Fry told the Smithsonian. “The use rate around 3M was quite phenomenal and that gave me an inkling that there would be a pretty good-sized market.”

Convincing the management of the Notes’ potential had taken three years. Bringing them to market would take three more. “Everything was new so it required all new means of manufacturing, all new chemistries of the material except the paper, and the means of getting it to the market – all had to be developed.”

The production was also beset with technical problems, and designing the required machines took several years. “It’s not just a matter of smearing a little glue on the paper. The product has to stick to paper but with less force than the paper sticks to itself. It’s a very precise adhesion target.”

The market introduction was equally tricky because the product was so novel – people did not understand the usefulness of Post-it Notes until they were given samples.

The sticky notes were not an overnight success. 3M’s management had serious doubts over the product’s potential, and market research concluded that the sales and customer base was very limited

A runaway success

But once they took off, they took off. Launched in April 1980, Post-it Notes soon became a mainstay of every office. In 1981, 3M named Post-it Notes its “Outstanding New Product”, accompanied by two Golden Step Awards for significantly profitable new products. Today, Post-it Notes are used in well over 100 countries around the world and have sparked a number of spin-off products.

The unique adhesive has also found further applications in areas as diverse as medical bandages to interior decorating.

No fortune but fame

Silver and Fry were inducted to the US National Inventors Hall of Fame and made members of 3M’s Circle of Technical Excellence and its prestigious Carlton Society, reserved for only the most important innovators. However, for all the millions 3M made from the product, neither of its inventors were entitled to any royalties – part of 3M’s strategy for encouraging the open exchange of ideas among employees is to severely limit the amount of financial gain an individual can make.

Today, Post-it Notes are used in well over 100 countries around the world and have sparked a number of spin-off products...in areas as diverse as medical bandages to interior decorating

What’s in a colour?

As for the distinctive canary-yellow colour of the ‘classic’ Post-it Note – it would be tempting to think that it’s the result of some serious thinking and market research which determined that the paper should ideally be light enough for use with any colour pen, but bright enough to stand out from the generally white papers they’d be stuck to. The truth is considerably more serendipitous.

After being asked the question via the company’s Twitter feed, Geoff Nicholson, the company’s former vp/technical operations, revealed that across the corridor from his laboratory the team managed to find some scrap paper which they’d used in their experiments. It was pure chance that the paper happened to be canary yellow.

“It was another one of those incredible accidents – nobody said they’d better be yellow rather than white because they would blend in. Afterwards we had a lot of people who said well it’s got a good emotional connection,” he said. “That’s a load of … whatever.”

Originally published in August 2012.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.