CCS: Why bother?

Carbon capture and storage costs money, so why bother? On the CCS Safari, Helen Tunnicliffe found out

ON the face of it, CCS makes no sense from a business perspective. While the cost of the process has dropped dramatically in recent years – by up to 50% according to estimates from Norway’s Technology Centre Mongstad (TCM) – it is still much more expensive than just emitting the carbon, despite various carbon pricing efforts.

For example, in 2005, the EU launched the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), requiring big emitters to buy permits for the carbon they emit. The price per ton currently sits at around €6/t (US$7/t). When I visited Norway last month, the consensus among the company executives gathered was that in order to really incentivise serious investment in CCS, that price needs to be nearer to US$50/t.

And yet, all the companies whose representatives I met on the CCS safari in Norway – Fortum, Norcem, Yara, Statoil and Total – are really excited to be involved and really keen to see the full-chain CCS scheme realised in the country. But why?

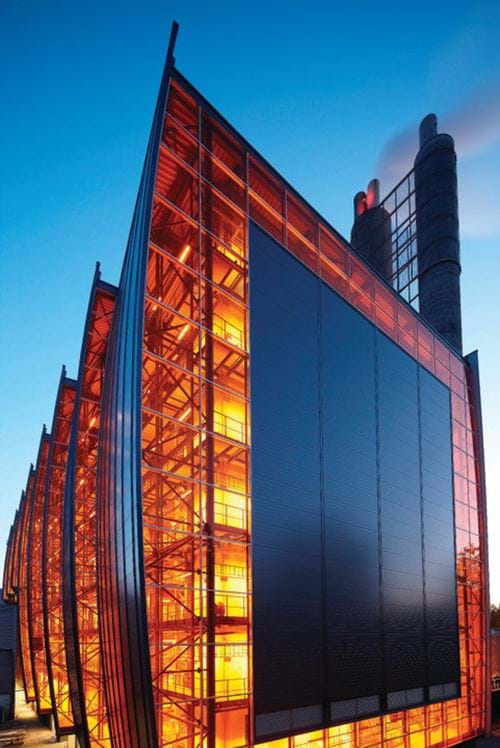

Fortum Oslo Varme

The Klemetsrud waste-to-energy facility provides district heating, cooling and electricity, and is run as a joint venture between Fortum and the City of Oslo. Some of the impetus for the CCS scheme at Klemetsrud naturally comes from the City of Oslo, which has extremely strict climate targets. Earlier this year it passed a climate budget, allowing carbon emissions to be accounted for in the same way as money in the fiscal budget. It also plans to reduce emissions by 50% by 2020 and by 95% by 2030. Oslo is set to be the 2019 European Green Capital.

Fortum was attracted to invest in the Klemetsrud plant by its environmental credentials, but CCS director Pål Mikkelsen explained that there are also sound business reasons. The market for waste-to-energy is growing as restrictions on landfill increase. Mikkelsen says that energy recovery is the best option for non-recyclable waste. In a changing world where lowering carbon emissions becomes a necessity, capturing carbon will make Klemetsrud more competitive in the waste market. The waste industry is already heavily regulated and taxed, with incentives available to be cleaner and greener.

“They use the carrot and stick in our business. If you do it, you get support and you will maybe pay less tax, if you don’t you’ll have to change anyway in ten years’ time,” he said.

In the past 20 years, there have already been many changes, including NOx removal and fibre filters to clean emissions.

“In ten years’ time, probably everybody will have to install CO2 capture one way or another, and we want to be a first mover,” Mikkelsen added.

This will enable Fortum to build up early expertise. The community will also benefit through cleaner emissions and more jobs, in turn helping the company through increased acceptance of plants and the technology.

Norcem

Norcem’s parent company Heidelberg Cement has a vision of zero emissions from its concrete products by 2030, but every decision is still driven by the need to be a profitable, growing business. Sustainability and corporate social responsibility are built into the company’s guiding principles, and this includes climate and environmental protection. As at Klemetsrud, environmental principles are a driving force behind the Norcem Brevik CCS project, but again, that is not all.

Per Brevik, director sustainability and alternative fuels, says that the cement industry is changing, partly as a result of the Paris agreement, and realising that CCS is necessary. There is also pressure from investors to reduce CO2 emissions. The Norcem Brevik plant already saves money and emissions by using waste and alternative fuels instead of coal, and gets subsidies to do so.

“This is the greenest cement plant in the world and we will keep it that way when we are the first with carbon capture,” Brevik said.

Yara

Yara, too, has a long-term ambition to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to zero. It has developed catalyst technology to reduce nitrous oxide emissions by 90% and has licensed the technology for use elsewhere through its environmental solutions business. It invests in research and development to reduce process emissions and has plans to use a zero emission, fully automatic, autonomous container ship from next year to transport the CO2 it already sells.

Becoming involved in the Norwegian CCS project is a natural fit for Yara’s climate ambitions. Yara recognises the move towards low-carbon industry and the risks that failure to innovate and change would pose to the business as new legislation is imposed.

The oil majors

Statoil has been a pioneer of CCS in Europe, and has been capturing and storing CO2 in the Sleipner field under the North Sea since 1996.

It is a crucial partner in the Norwegian demonstration project, having won the contract for carbon storage, and is one of the industry partners in TCM. Torbjørg Fossum, project leader in Statoil New Energy Solutions, explained that Statoil is essentially preparing for the low-carbon future.

“We realise that our business is under pressure. There are elemental changes in the world that we are all aware of. The most obvious one is that we are exposed to low oil prices, and also climate change,” she said. “To make it simple, we realised that we had to get costs down, and we had to get emissions down.”

Statoil New Energy Solutions is partly tasked with achieving this, bringing together Statoil’s renewable wind assets and its CCS interests. Statoil’s own climate roadmap backs the need for carbon capture: “Investment in low carbon technologies, such as carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) is vital to reduce overall emissions from oil and gas and other sectors.”

Fossum told us that the full-scale CCS chain in Norway is one of the most exciting CCS projects in the world. It may well be a catalyst for other European CCS projects, which could also store their CO2 in the same Smeaheia formation under the North Sea.

CCS may also open up new areas of business for Statoil. Statoil is investigating making hydrogen from natural gas. The process produces CO2 as a byproduct, but this could be captured and stored, proving a clean and abundant source of hydrogen. There is still ample gas available in Statoil-operated fields under the North Sea, and this option would allow Statoil to maintain an important part of its business and still meet climate goals. The company is in discussions with Vattenfall and Gasunie to convert a turbine at the Magnum power station in Eemshaven, the Netherlands, to run on hydrogen, and is involved with the H21 project in Leeds, UK, to heat homes using hydrogen instead of gas.

Statoil and fellow TCM partner Total are both part of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI), alongside companies such as Shell, BP, CNPC and Saudi Aramco, to invest US$1bn over ten years in emissions reduction research, of which up to half will be invested in CCUS.

For Total, the fourth largest oil company in the world, CCUS is embedded within the company’s business strategy, as part of its plans to reduce the carbon intensity of its production mix. This includes increasing the percentage of gas, and pulling out of higher-carbon industries such as coal. CCUS research programme manager David Nevicato, a chemical engineer by training, explained that the IEA’s 2˚C scenario estimation shows that in 2040, 44% of energy will still need to come from fossil fuels. Total is studying a range of options for decarbonisation, but CCUS will be an important part. From next year, it will spend 10% of its US$600m research budget on CCUS.

Nevicato said that Total sees CCUS as a genuine business opportunity. Much like for Statoil, CCUS offers the chance to maintain its main business while still lowering carbon emissions, as the world moves away from fossil fuels. Gas power with CCS can provide low-carbon energy to cover for intermittent renewables, while if CCS is combined with biomass, there is even the potential for negative emissions.

“The energy world will move towards an electricity world in the future, and gas power with CCS can provide that,” he said.

Nevicato laid to rest the idea that CCUS has to be prohibitively expensive, by comparing the cost per ton of CO2 abatement of different energy generation methods.

“Our estimation [of the carbon abatement price] for gas power with CCS is about US$200/t of CO2. For solar it was about US$500/t, and don’t forget that for solar energy there are a lot of subsidies,” he said.

So that’s why

For all the companies I met, it all seems to come down to two main driving forces – corporate social responsibility and sound business reasons.

Sooner or later, governments will begin to crack down on emissions, as the reality of meeting the Paris agreement target of keeping global warming to below 2˚C bites. The UN climate panel estimates that it will be 137% more expensive to meet the Paris target without CCS. The International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, go one step further, saying that without CCS, the Paris target cannot be met at all. To meet the Paris targets, the IEA says that 6bn t/y of CO2 must be captured and stored by 2050.

Suddenly, CCS doesn’t look so bizarre, especially for industries like cement and fertilisers which cannot help but produce CO2 as part of the production process. CCS will also help to decarbonise conventional energy generation while renewable energy develops to a level where it is both practical and economically feasible for it to completely replace fossil energy.

Some major companies back the Norwegian CCS demonstration project, and have good reasons for doing so. If other companies sit up and take notice, it could start the revolution.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.