Now or never: emissions need to peak by 2025 says IPCC

IN its latest report, the IPCC has warned that emissions must peak by 2025 and halve by 2030 if the world is to keep to the 1.5oC target. It calls for major reductions in fossil fuel use alongside rapid scaling up of mitigation technologies such as carbon capture and storage.

This is the third report as part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth assessment report. The first detailed the physical science behind human-caused climate change, and the second outlined the impacts that climate hazards are having on humanity and industry. The third report, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change, details potential mitigation measures as well as warning that there is little time left to enact those measures.

Very narrow window for action

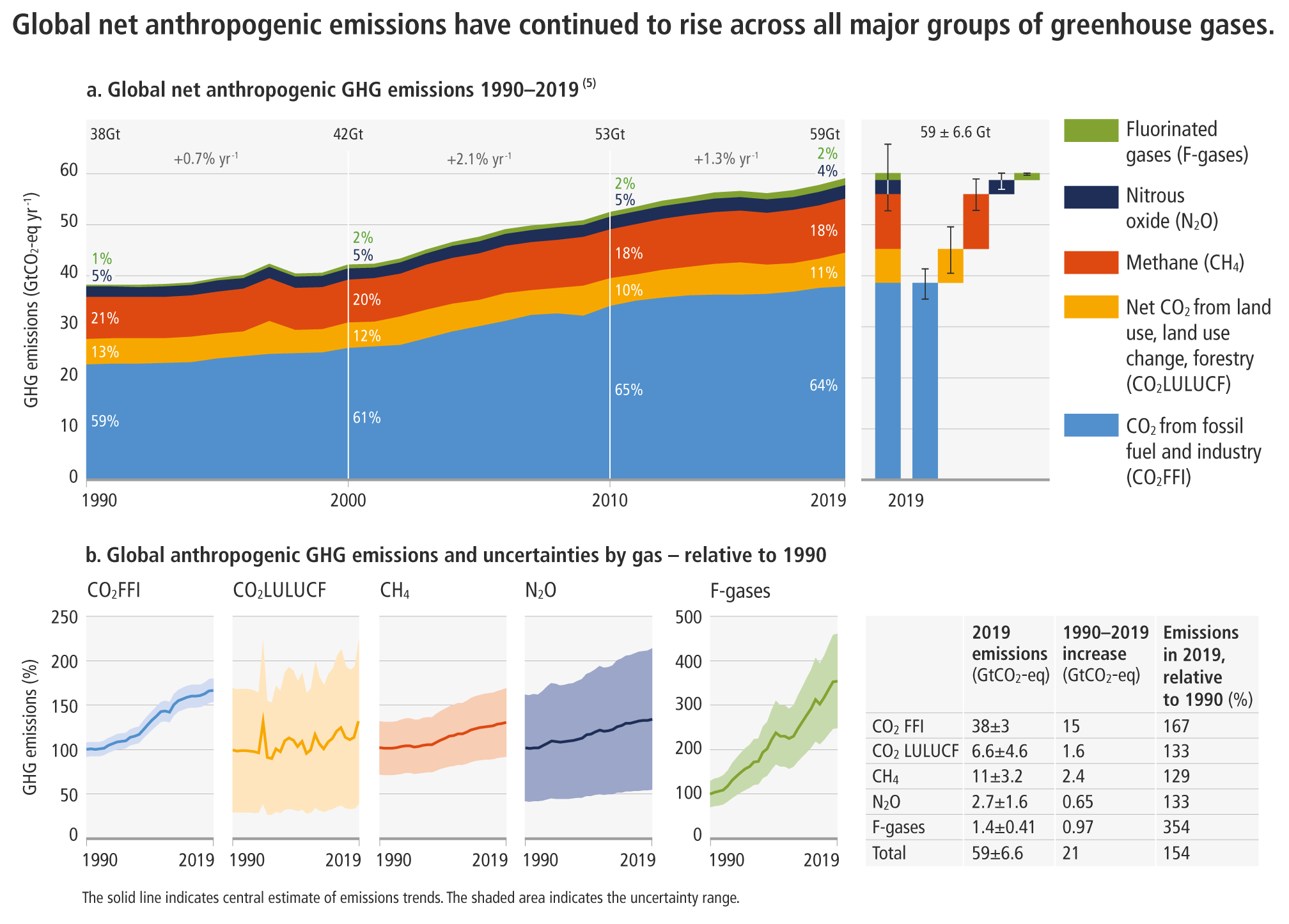

In 2018, the IPCC released a special report saying that in order to limit warming to 1.5oC, emissions need to fall by 45% by 2030 from 2010 levels. However, emissions have not fallen in the last four years. The new report now says that to keep to the 1.5oC target, global greenhouse gas emissions will need to peak by 2025, CO2 emissions need to fall by 48% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels, and methane emissions need to fall by 34%.

The IPCC admits that even if this trajectory is taken, it is “almost inevitable” that there will be a small amount of overshoot, where the average global surface temperature goes above 1.5oC from pre-industrial levels, before dropping back down again. Current climate pledges made at COP26 last year put the world on track for 2.8oC of warming.

Halving emissions by 2030 is still possible if action is taken immediately. This would require more upfront investment and a faster pace of change than delaying action, but would ultimately have greater economic and health benefits.

Jim Skea, IPCC Working Group III Co-Chair, said: “It’s now or never, if we want to limit global warming to 1.5°C . Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible.”

Targets can’t be met without CCS

Carbon capture will be critical to keeping to the 1.5oC target, the IPCC said, and it called for a major scaling up of CCS technologies. Without CCS, fossil fuel use needs to drop by 100% for coal, 60% for oil, and 70% for gas by 2050 compared to 2019 levels. If CCS is used, this becomes 95% for coal, 60% for oil, and 45% for gas. It cautioned that CCS generally can’t capture all post-combustion CO2 so the remainder would need to be offset elsewhere.

The report said that CCS is most mature in the oil and gas sector, compared to other sectors where it is needed such as power, chemicals, and cement production.

If an overshoot occurs on the 1.5oC target, carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies – including options such as reforestation – would need to draw down almost a decade of CO2 emissions to bring warming down.

Michael Wilkins, Professor of Practice at the Centre For Climate Finance and Investment, Imperial College Business School, said: “The significant decrease in the cost of low and zero carbon technologies over the past decade, especially in solar and wind power, demonstrates that with the right policy incentives and economic frameworks, climate change mitigation can be financed at scale and relatively quickly. The same logic could equally be applied to new technologies being developed for carbon removal, such as direct air capture, where currently costs are prohibitively expensive for large scale development.”

Jon Gibbins, Professor of Power Plant Engineering and Carbon Capture at the University of Sheffield, said: “It […] very urgently needs to be recognised that new fossil fuel facilities do not necessarily have to lock in future GHG emissions, provided that CCS readiness becomes an integral part of new infrastructure developments. With a suitable choice of location, and some very low-cost provisions in the original plant, CCS will then be able to be retrofitted later with minimal cost and reduction.”

Steve Smith, Executive Director of CO2RE and Oxford Net Zero, University of Oxford, said: “With carbon removal getting lots of the headlines, it’s crucial to remember we won’t stop climate change without all the other stuff in the IPCC report: cutting energy waste, cutting fossil fuels if the carbon isn’t captured and stored, better diets, and not cutting down forests. To put things into perspective, the IPCC pathways suggest about 3-4bn t of removals to achieve net zero CO2 emissions, 8bn at a real stretch, while CO2 emissions are cut by something like 40bn t.”

Fossil fuel infrastructure at risk of becoming stranded assets

The report said that fossil fuels account for around 80% of primary energy today and that to keep to the 1.5oC target, this needs to fall to 59-69% in 2030 and 25-40% in 2050.

It notes that “reducing GHG emissions across the full energy sector requires major transitions, including a substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use, the deployment of low-emission energy sources, switching to alternative energy carriers, and energy efficiency and conservation.”

The projected emissions from current and planned fossil fuel infrastructure until end of lifetime would far exceed what can be emitted to keep to the 1.5oC target. The fossil fuels emissions would amount to 850bn t of CO2, whereas the remaining cumulative CO2 emissions in pathways limiting warming to 1.5 can be no more than 510bn t of CO2.

Existing policies and Paris Agreement pledges (nationally determined contributions – NDCs) are insufficient to prevent an increase in fossil fuel infrastructure, and current investment decisions are critical to avoid exceeding the remaining carbon budget. It warned that delays in mitigation will “increase carbon lock-in and could result in large-scale stranded assets if stringency is subsequently increased to limit warming.”

The report said that both fossil fuel infrastructure and resources are at risk of becoming stranded assets. Around 200 GW of fossil fuel electricity generation will need to be retired prematurely after 2030 to limit warming to 2oC, and limiting it to 1.5oC will “require significantly more rapid premature retirement of electricity generation capacity”, with coal and gas-fired power plants retiring around 30 years earlier than in the past.

It said that exploration and the issuing of new licences for fossil fuel resources “may cause economic as well as non-economic issues”. Around 30% of oil, 50% of gas, and 80% of coal reserves will be unburnable to limit warming to 2oC, and “significantly more reserves are expected to remain unburned if warming is limited to 1.5°C.”

Investing in new fossil fuels infrastructure is moral and economic madness. Such investments will soon be stranded assets – a blot on the landscape and a blight on investment portfolios.

António Guterres, UN Secretary-General

Fossil fuel infrastructure and resources becoming unusable would lead to US$1trn–4trn in stranded assets under a 2oC scenario, and significantly more under 1.5oC. It said that stronger near-term mitigation will reduce premature retirements of fossil infrastructure and that “decommissioning and reduced utilisation of existing fossil fuel installations in the power sector as well as cancellation of new installations are required.”

António Guterres, UN Secretary-General, said: “Climate scientists warn that we are already perilously close to tipping points that could lead to cascading and irreversible climate impacts. But, high‑emitting governments and corporations are not just turning a blind eye, they are adding fuel to the flames. They are choking our planet, based on their vested interests and historic investments in fossil fuels, when cheaper, renewable solutions provide green jobs, energy security and greater price stability.

“Investing in new fossil fuels infrastructure is moral and economic madness. Such investments will soon be stranded assets – a blot on the landscape and a blight on investment portfolios. But, it doesn’t have to be this way. Today’s report is focused on mitigation – cutting emissions. It sets out viable, financially sound options in every sector that can keep the possibility of limiting warming to 1.5°C alive.”

Moving away from fossil fuels

The emissions due to the generation of electricity and heat must be eliminated even with increasing demand. The IPCC said this can be done through electrification of buildings, transport, and industry.

Cost reductions mean that in many parts of the world renewables are cheaper than fossil fuels. Since 2010, unit costs for solar power has fallen by 85%, lithium ion batteries by 85%, and wind energy by 55%. Deployment has increased rapidly at the same time.

The report said digitalisation can help to improve energy efficiency. Technology such as sensors, digital twins, the Internet of Things (IoT), and AI can improve energy management in all sectors and accelerate adoption of low-emissions technologies. However, there can be disadvantages, such as increasing electronic waste and negative impacts on jobs. It cautioned that digitalisation for decarbonisation needs to be appropriately governed.

Nuclear energy “can deliver low-carbon energy at scale” but doing so “will require improvements in managing construction of reactor designs that hold the promise of lower costs and broader use.” There are also challenges with disposal of radioactive waste that need to be addressed.

Hydrogen can be used in industrial sectors which are otherwise difficult to decarbonise, however it notes that as a general rule it is more efficient to use electricity directly and avoid conversion losses from hydrogen production from electricity.

Sir Jim McDonald, President of the Royal Academy of Engineering, says: “While the current energy crisis is the first big challenge of the just transition, it brings with it the opportunity to pivot away from fossil fuels towards cheaper renewables and a low carbon energy system as well as to support vulnerable people through home energy efficiency retrofit. The report makes it clear that the cost of the transition cannot be an excuse for delay – the economic case made by the report authors is strong, highlighting that lower cost mitigation options could reduce global GHG emissions by at least half the 2019 level by 2030, while still allowing GDP to grow. All of this means that the solution to both the UK’s short term energy crisis and our long term climate challenge are the same; redoubling our efforts on mitigation policies that focus on shifting from fossil fuels to renewables, reducing demand, and retrofitting buildings.”

The challenges of decarbonising industry

Industry emissions have been growing faster than any other sector since 2000 due to increased extraction and production of basic materials. In 2019, industry accounted for 24% of global emissions, but when indirect emission from power and heat use are taken into account, this rises to 34%. The emissions come from fuel combustion, process emissions, product use and waste. The chemicals industry was responsible for 10% of global direct industrial emissions in 2019, with ammonia production having the highest emissions intensity in the sector.

Decarbonisation options include electrification, switching to low carbon fuel and feedstocks, CCS, and recycling. It said that all decarbonisation options for industry involve scaling up infrastructure, as well as phasing out or converting existing industrial facilities.

Electrification – either directly or using hydrogen from electrolysis – is a key mitigation option for industry. Energy efficiency can be improved by using heat-to-power, which is currently an underutilised option. It said that with improved technologies, 40 – 57% of waste heat with temperatures above 150oC could be used for power generation. Using materials more efficiently can also lead to emissions reductions in industry, such as making lighter-weight products, re-using components, and minimising waste.

Potential alternatives to fossil fuels in industry include biofuels, hydrogen, ammonia, and net zero synthetic hydrocarbon fuels. However it noted that how these alternatives are made is important as they are not necessarily lower emitting, for example biofuels are not necessarily GHG neutral due to factors such as land use change and fertiliser use.

The report noted that for most basic materials such as metals and chemicals, low- or zero-GHG production processes are at pilot or near-commercial scale. Some processes are at commercial scale but are not yet established industry practice. For products that still require carbon – such as aviation fuel, plastics, and solvents – it will be important to close the loop with emissions. This can be done through increased mechanical and chemical recycling, using biomass and waste feedstocks, and using CO2 captured from industrial sources or direct from the air as a source of carbon feedstock. It noted that price is the main factor in decarbonising the main industrial feedstocks such as hydrogen, ammonia, methanol, carbon monoxide, ethylene, propylene, and aromatic chemicals.

Circular economy solutions can help industry reduce emissions but “careful evaluation is needed from a lifecycle perspective since some recycling activities may be energy- and emission-intensive, for example, chemical recycling of plastics”. It noted that circular economy solutions can be applied on different levels: micro-level within a single company such as cleaner production; meso-level between three or more companies such as industrial parks; and macro-level which is cross-sectoral cooperation such as using waste materials as industrial feedstocks. Each requires different tools, policies, and eco-design regulations.

The report said that cement and concrete are currently overused as they are inexpensive and durable, and that emissions can be reduced by 24–50% by only using well-made concrete where necessary. CCS will be essential for eliminating emissions from cement production in the near to medium-term until alternatives to Portland cement are commercialised.

It notes that steel was responsible for 20% of global direct industrial emissions in 2019 but that steel demand could be reduced by 40% through measures such as manufacturing long-lasting steel and reusing steel where possible. It is possible to reduce emissions via several technological options such as hydrogen direct reduced iron (DRI) production.

If multiple available and emerging options are deployed by emissions-intensive industries, it is still possible to achieve close to net zero emissions by 2050.

We have the knowledge and the technology

Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), said: "The last two decades saw the highest increase in emissions in human history, even though we know how much trouble we are in. The next decade cannot follow the same pattern if we are to hold global warming this century to 1.5oC. Half-measures won't halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, which is what we need to do. We need to go all in.

"The IPCC tells us that we have the knowledge and technology to get it done. Through a rapid shift from fossil fuels to renewables and alternative fuels. Through moving from deforestation to restoration. Through backing nature in our landscapes, oceans and cities. Through transforming our cities into green and clean spaces. And through behaviour change to address the demand side of the equation.

“Now such an opportunity presented itself when countries rolled out stimulus packages to help kick-start economies as we faced the Covid-19 pandemic. But on the ‘green scorecard’, we failed – loud and clear. Once again, we find ourselves with an opportunity as countries seek out alternative sources of energy. Immediate needs must be met, to heat homes and keep lights on. But as we rethink hydrocarbon suppliers and our dependency on fossil fuels, the solution has to be in kick-starting the transition to renewable and cleaner sources of energy.”

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.