DNV GL: Energy demand will plateau in 2030

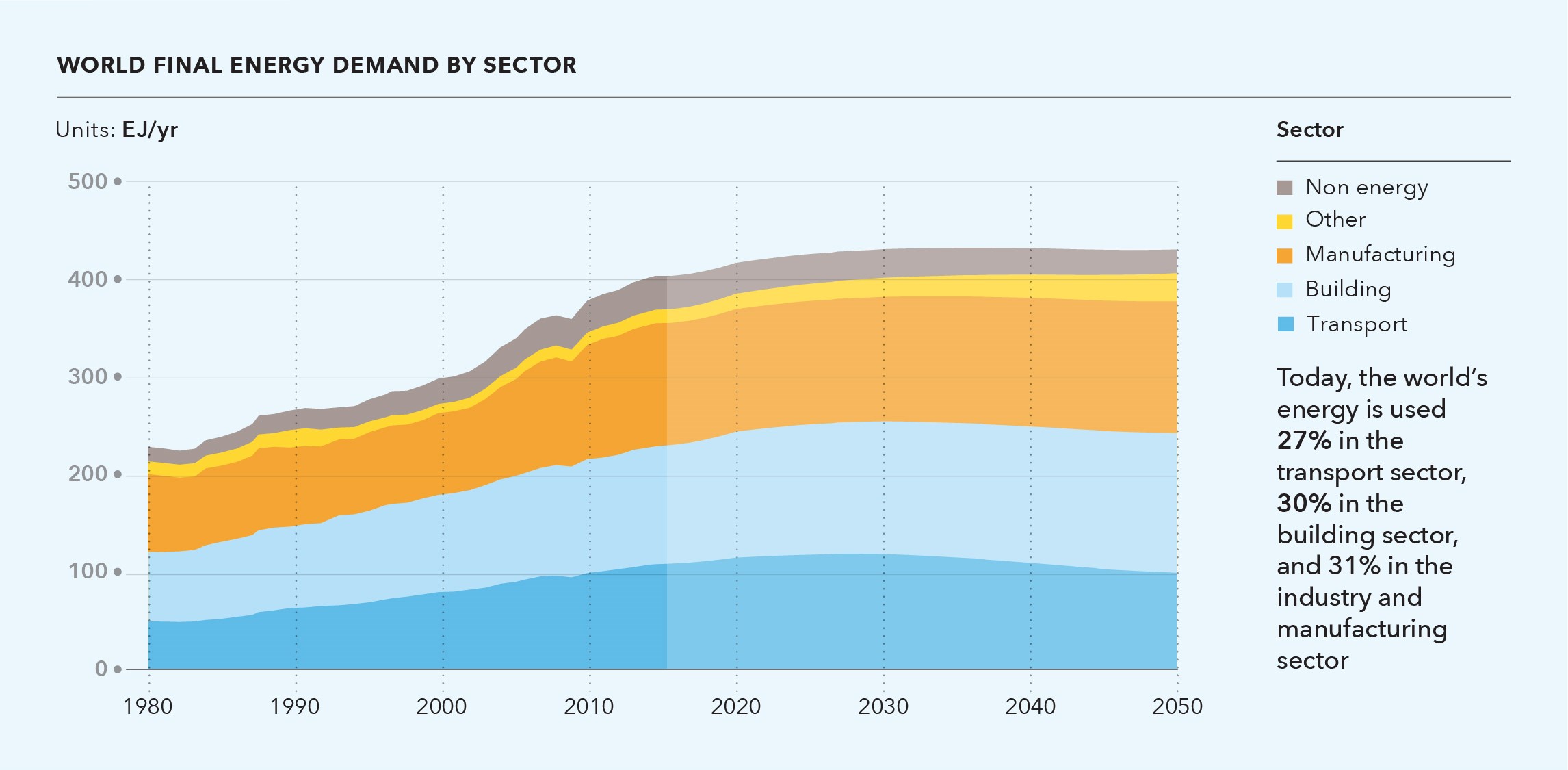

RISK MANAGEMENT firm DNV GL predicts that global energy demand will peak in 2025 and plateau after 2030, in its first Energy Transition Outlook published on 4 September.

The Energy Transition Outlook 2017 looks at the likely changes within the energy sector between now and 2050, based on DNV GL’s own model of the world’s energy system, taking into account supply, demand, source, and end-use of energy.

Unlike predictions from other companies, which have largely produced ‘scenarios’ based on a range of variables, DNV GL has set out just the most likely future situation, based on available technologies and avoiding as yet-undeveloped breakthroughs such as nuclear fusion. 70% of DNV GL’s business relates to energy, and it is the largest technology advisor to both the fossil fuels and renewable energy industries, so the company believes it is in a good position to offer a balanced view.

The Outlook was launched today at an event at Bloomberg’s London offices by DNV GL CEO Remi Eriksen.

“At the moment, for the first time since perhaps the Middle Ages, humanity will start to use less energy on an aggregated level,” he said. “But how can that possibly be? I hear you asking yourselves. The population will be growing, the economy will be growing, and surely energy use goes hand in hand with both of these factors.”

Actually, the DNV GL model predicts a decoupling of energy demand growth from emissions, GDP and population growth. In 2015, the average European required 135 GJ/y of energy. By 2050, this is expected to fall to 76 GJ/y. There are a number of reasons for this. Energy efficiency is predicted to grow, resulting in lower energy demand per capita. In 2015, 1 MJ of energy resulted in US$0.14 of GDP. In 2050, this will rise to US$0.34 of GDP. Electricity, for example for transport and heating, is likely to become the largest energy carrier, from 18% now to 40% in 2050. It is more efficient, with emissions further reduced as energy generation switches to renewable sources. As emerging economies develop, the growth of their economies will slow as they move to more service-based industries. OECD growth will be very low. By 2050, renewables will account for half of the global energy supply, driven largely by wind, use of which will increase 80-fold compared to today, and solar energy which will increase 30-fold.

Oil and gas currently accounts for 53% of the global energy demand but by 2050, this will have fallen to 44%. Gas is cleaner and more efficient than oil. Demand for gas will therefore likely overtake oil by 2034, becoming the world’s primary energy source. It is expected to hold this position to 2050 though its use will begin to decline in 2040. Meanwhile, coal use has already peaked and will begin to decline.

Electric cars are predicted to reach cost parity with conventional petrol and diesel cars by 2022, and by 2033, half of vehicles will be electric. Electric cars are four times more energy efficient that those with internal combustion engines.

By 2050, energy-related CO2 emissions will be half what they are today. More needs to be done to reduce energy demand and decarbonise production, however. Despite the falling energy demand, DNV GL’s Outlook predicts that the world will not meet the Paris climate targets to keep global warming to below 2˚C by the end of century.

The Outlook looks at likelihood of meeting the Paris agreements in terms of an ‘energy budget’ – how much carbon can be emitted before it is likely that the temperature rise target will be breached. The 1.5˚C temperature rise carbon budget will be ‘spent’ in just four years time at current levels, according to DNV GL’s models. The 2˚C carbon budget will be spent by 2041. DNV GL estimates that the temperature rise will be in the region of 2.5˚C, although it admits that there is some uncertainty. This failure, said Eriksen, should be “a very big wake-up call”.

Ditlev Engel, CEO energy of DNV GL said: “Decarbonisation is not just an engineering challenge but also a governance one. Therefore bold regulations and policies are needed. I think also, in this sense it’s very important to use a report like this to try to help people to connect the dots in terms of managing this carbon budget in the best possible way.”

Two sector specific supplements have been produced in addition to the main report, covering the forecasts specifically for the oil and gas industry, and for renewables, power and energy. A supplement looking at the maritime sector will follow later in the year.

“The profound change set out in our report has significant implications for both established and new energy companies. Ultimately, it will be a willingness to innovate and a capability to move at speed that will determine who is able to remain competitive in this dramatically altered energy landscape,” said Eriksen.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.