Arup: Organic waste could be used in construction

A NEW report from engineering major Arup says that organic waste such as that from bananas, potatoes and maize could be used to make materials for construction with much lower environmental impact.

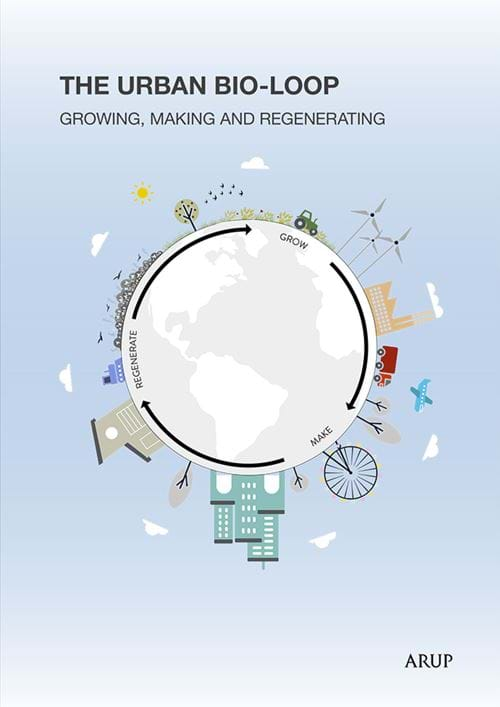

Construction accounts for a large proportion of raw material use around the world. In the UK, for example, the industry accounts for 60% of all raw materials used. Replacing some of those raw materials with bricks, insulation and partition boards made from waste materials would make the industry much more sustainable. The authors of The Urban Bio-Loop: Growing, Making and Regenerating envisage that waste from construction would be recycled to make more new construction products, and unusable waste returned to the soil to grow more crops, creating a truly circular economy.

In 2014, Europe produced more than 40m of dried solid organic waste from agriculture and forestry. Organic waste may be recovered and recycled or reclaimed, incinerated for waste recovery, or landfilled. The value of organic waste incinerated for energy recovery is around €0.85/t. However, if that organic waste was used to make, for example, interior cladding, it could then be worth €5–6/t.

There are six main potential uses of organic waste in construction, according to the report – flat boards for interior partitions, furniture, acoustic absorption, thermal insulation, carpets and other floor coverings, and what is known as the building envelope, basically the outer shell such as the roof and exterior cladding.

The researchers looked at 12 different types of solid organic waste and assessed the uses and potential for each. These are sugarcane, cellulose, maize, sunflower, peanut, seeds/stalks/leaves, banana, potato, hemp/flax, rice, wheat and pineapple.

Sugarcane bagasse for example can be pressed into stiff boards for internal walls and floors. Dried corn cobs can be used as the filler in so-called ‘sandwich boards’, between two other thin boards made from another organic waste, for use in doors and interior walls. Peanut shells can be turned into moisture and flame-retardant partition boards. Banana fibres can be processed into textiles and carpets. Potato peelings can be turned into ‘potato cork’, for insulation and sound absorption. Rice husk ash can be incorporated into cement to make lower density concrete blocks.

According to the report, the move towards waste-based materials will lead to the creation of many more SMEs and startups to make the products and implement their use. Many SMEs have already begun to make construction materials from recycled organic waste, and several are mentioned in the report itself.

The report includes a case study of the Italian city of Milan, which has the highest recycling rates in the world for solid organic waste, following more than two decades of a dedicated collection programme. Currently, the city and metropolitan area collects around 130,000 t/y of solid organic waste. The authors say that if 10% of the potential organic waste available was diverted to make flat boards for construction, this would make around 8m m2 of boards.

The authors say that for such a circular economy to be possible for the construction industry, there will need to be much wider stakeholder engagement, and a regulatory framework to allow easier access to the waste and make it more attractive to investors.

“As one of the world’s largest users of resources we need to move away from our “take, use, dispose” mentality. There are already pockets of activity, with some producers making lower-CO2 building products from organic materials. What we need now is for the industry to come together to scale up this activity so that it enters the mainstream. An important first step is to work with government to rethink construction codes and regulations to consider waste as a resource, opening up the opportunity to repurpose it on an industrial scale,” said Guglielmo Carra, European lead for materials consulting at Arup.

Arup has implemented several green construction projects, including the concept Circular Building, in which all the components can be reused or recycled at the end of the building’s life, BIQ Hamburg (pictured above), which includes façade panels filled with algae to generate heat and biomass to power the building, and the Mushroom Tower (pictured above), a temporary structure made from bricks grown from mushrooms. It has also developed the BioBuild biocomposites system comprising natural fibres and natural resin.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.