Ethics Series: A Circle of Trust

Joan Cordiner discusses the world of professional ethics

IMAGINE you are in India visiting a plant. You realise the unit operation you are having trouble with is a copy of patented equipment. What do you do? Or perhaps your company is taken over by another company owned by a foreign government with alleged human rights violations? What do you do? Maybe you work in a country where bribes are common practice to obtain a permit? What should you do? These are all situations that I have faced.

Ethics as an individual

In our globalised companies and outsourced production these are the sorts of issues we can face. I was unprepared! I had, however, several excellent mentors that encouraged me to ask questions and I found their thoughts invaluable: a problem shared is a problem halved, perhaps.

So, let’s start there. Most of us don’t work on our own, and therefore asking our colleagues and managers can help. In the case of the Indian plant example above, I found out that tax on bringing equipment into India at the time was more than 75% of the purchase price of equipment. Did that justify their actions? Perhaps the Indian supplier had a licence to use the technology given the tax situation? What’s more, as a visiting engineer on a toll site to help with a startup, would it even be your place to challenge the project manager? How far would you go asking questions? Is it sufficient to raise the concerns to your manager? These are not easy questions and unfortunately there are no easy answers. Often, the best course of action depends on the minute details of the situation, your company’s ethical code of conduct, and its actual practices.

In my case, I asked and was reassured by the answers, so I did not need to escalate the matter. It also meant that I could set up the equipment as expected, given it was identical to the patented piece of equipment I was familiar with.

Most large companies have ethical codes of conduct and statements. These are typically backed by policies about issues such as bribes, and intellectual property, to follow the highest standard of the company or the country’s regulations whilst complying with the regulations of every country where the business operates. For most of you, your preparation for following these measures will largely consist of online training courses covering topics like procurement, insider trading and doing business with integrity etc. But for the recent graduate who might have covered some basic ethics in their accredited course, there is so much more to learn. Lack of uniformity on how these ethical codes are applied can have significant consequences, as we learned in the first article in this series (TCE issue 971). Bhopal happened where the company was inconsistent in its standards across its global organisation.

I currently work as Professor and Head of Department at the UK’s Sheffield University and previously have worked as a process engineer, technical manager and global risk lead in the chemicals, pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals industries, retiring from Syngenta in 2019.

A couple of years ago, a very engaged, year-2 chemical and bio engineering student at Sheffield, Aoife Campbell challenged as to why we were inviting a particular company in for interviews and to partake in our Industry Advisory Board. Aoife’s point was that, despite a strong company values statement on its website, its actual practices were in contradiction and there were volumes of evidence to implicate the organisation in causing significant environmental damage in South America through its operations there. Together, we looked at some websites that Aoife had researched. I encouraged her to look at some companies that have, in her opinion, a very good track record. The stunning thing to our student was that if you look up any company there are reports of environmental releases, court cases and negative publicity. So, given this, where do you draw the line?

With good environmental regulations, all companies must report in various countries any release above the permitted limits. Of course, there is a significant difference with a small number of small releases versus significant spills or leaks that are ongoing or unmitigated. Furthermore, another layer of complexity is added to the problem by so-called corporate “greenwashing”, which is perceived to be abundant in industry and production. The question our student wanted to answer is: how will job seekers know what companies really do? And does it match what they say they’re doing? And in answering this, another dilemma is faced: how do you decide who you are prepared to work for?

Young engineers are reasonably concerned about sustainability. There will be climate change imperatives that are going to affect their engineering careers much more than previous generations of engineers

In a previous article (TCE issue 971) by Dame Judith Hackitt we were challenged to think about safety incidents and where people or engineers could have acted and prevented incidents such as Grenfell and the Challenger space shuttle disasters. Issues of safety are of obvious paramount importance when it comes to ethical practice. However, there is growing recognition of ethics being intrinsically linked to environmental sustainability. Impacts posed from ignoring these issues – particularly as the effects of the climate disaster continue to escalate – have human impacts on an enormous scale that is hard to comprehend.

Our current generation of students and young engineers are reasonably concerned about sustainability. There will be climate change imperatives that will affect their engineering careers much more than previous generations of engineers. They have personal decisions to make about who they are willing to work for and in decisions made in their work.

For me that question challenged me a few times as my employers demerged and merged. I always came back to a decision I made after an explosion in Grangemouth – that I felt in my home miles away as a secondary schooler – that it would be better to be part of the solution to make a positive impact than to criticise from the outside. Of course, this was along with seeing the strong values lived out and reassurance that wouldn’t change over the changes in ownership.

Professional requirements from Chartership and in IChemE accredited degrees

We have a personal requirement to work ethically. It’s part of our accredited degree, it’s part of our chartership, and part of the requirements of most of the companies we work for.

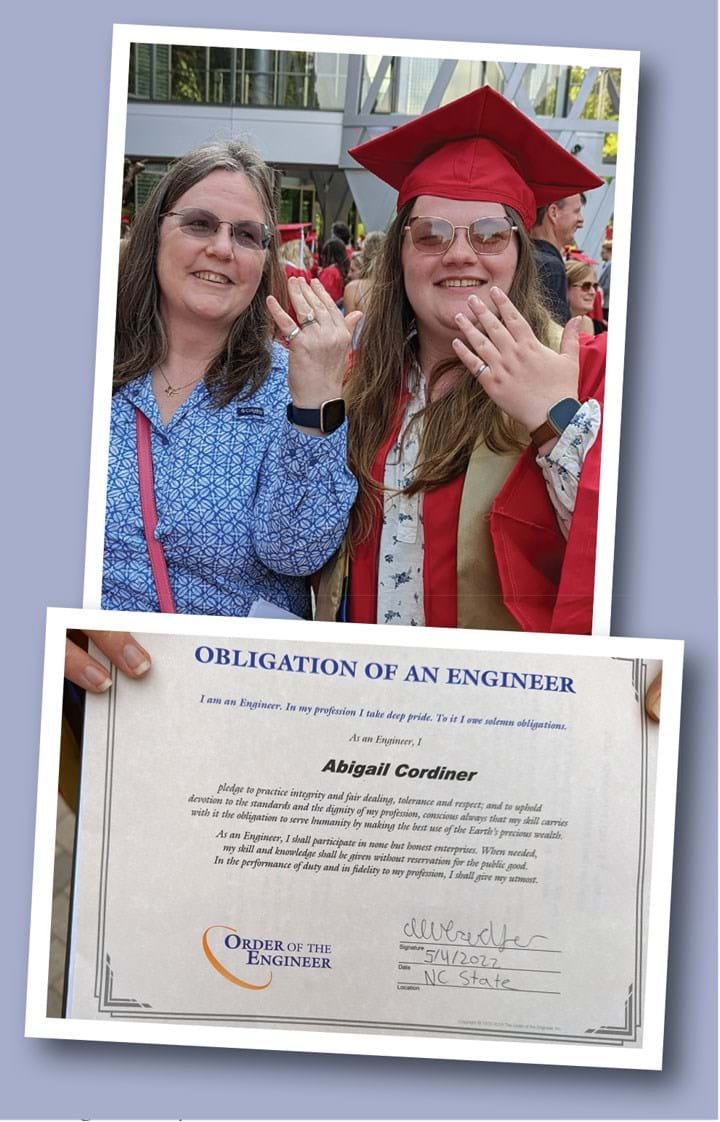

In Canada and parts of the US, graduating engineering students are invited to take The Oath of the Engineer. I took this oath, as did my daughter on recently graduating in chemical engineering at North Carolina State University.

The Oath reads:

This tradition started with engineers who were working on a replacement Quebec Bridge after the previous bridge collapsed, due to faulty engineering calculations and miscommunication1. Seventy-five men died. The oath was created in 1922 by Rudyard Kipling at the request of seven past-presidents of the Engineering Institute of Canada. The engineers were given rings made of iron – legend has it, from the fallen bridge – to wear on the little finger of the dominant hand. When engineers were working on drawings and documents, the ring would rub against the paper, reminding them of their responsibilities and the potential impact of their decisions.

We don’t have this in the UK on graduating. Would you be prepared to take such an oath? If you were to write one, what – in our day and age – should be included? As part of a Royal Academy-funded project, Diversity Confidence in Engineering (DiCE) at the University of Sheffield is looking at bringing in such an oath, or charter of an engineer. We asked a group of stakeholders what they thought should be included. If you were to compare this with what I would have thought on graduating three decades ago the list now includes much more about diversity, inclusion, climate change, globalisation, interacting with very different cultures.

So have professional ethics changed? Are they constantly changing? In the UK, the RAE has published Engineering Ethics: Maintaining Society’s Trust in the Engineering Profession2, in collaboration with other engineering discipline institutions including IChemE. This guidance consists of the following four foundations of ethical conduct

- Honesty and integrity.

- Respect for life, law, the environment and public good.

- Accuracy and rigour.

- Leadership and communication.

These are drawn from the Statement of Ethical Principles, first published in 2005 by the Engineering Council and the Royal Academy of Engineering, reviewed and updated in 2018. These four pillars are used to underpin the ethical expectations for professional engineers. Engineers in the UK are expected to adhere to these guidelines as a condition of their chartership.

The report notes: “In a keynote speech to the Engineering Ethics Conference in 2018, Professor Chris Atkin FREng CEng, Chair of the Engineering Council, suggested…embedding ethical culture and practice in the engineering profession would embrace other important professional behaviours such as operating sustainably, inclusively and with respect for diverse views…Today, sustainability is now being more actively addressed by engineers, owing to the greater awareness of the climate emergency, particularly by younger generations who will reap the consequences of inaction. Inclusivity now has a much higher profile because of the convincing narrative of both the benefits of inclusive recruitment and the retention of talent.”

There is a growing transition to regard sustainable practice and the impact on the triple bottom line as an obligation of a professional engineer3.

In the last century engineers and the projects we work on have the potential to impact the environment and millions of individuals to an unprecedented and cumulative effect, with the potential to last for extensive periods of time4.

Engineers joining the profession now have a much more complicated world in which to work: we can work on global projects from our home office, working in different cultures. We have to interact in a cyber-connected world that adds extra layers of complexity.

In his book The Art and Ethics of Being a Good Colleague5, Michael Kuhar guides us in working not just as individuals but as colleagues who impact each other.

We suggest that we think about ethics on three levels: interpersonal, leadership and interorganisational. The interpersonal level refers to the professional engineer’s conduct with colleagues. These colleagues will have varying disciplines as well as a variety of sociocultural backgrounds. Reviewers of Kuhar’s book note that strong collegial ethics will improve individual and organisational effectiveness. If we have learned anything through the Covid pandemic, perhaps also better interpersonal ethics can improve our enjoyment and fulfilment at work.

The second tier is the leadership level. The demands of engineering professionals are much more significant at this scale, as there are subordinates whose behaviour and conduct are directly influenced by their actions in addition to what is verbally encouraged in their working environment6. Literature indicates that ethical leadership improves work engagement and therefore improves work performance, as well as offering improvements to the wellbeing of employees7. We will cover the third tier of interorganisational later on in this article.

Ethics when we become leaders and how it impacts those you lead

For many who become leaders there is a further requirement: we need to lead by example. If we borrow from process safety thinking, it’s possible to normalise deviance. That is, we can set the wrong example and thereby show it to be acceptable for others. Or we can turn a blind eye – that is tacit acceptance.

But how does this responsibility change as the scale of our leadership grows? When we have the power to make decisions on large projects – on the direction, and location investment and in who we hire and promote, for example. Hopefully people won’t face the situation of being asked to hide or change results, to suit a department or company’s commitments or key metrics, but court records prove this still occurs.

Over the years I have interviewed a surprisingly high number of people who report wanting to leave their current or previous company due to ethical or safety decisions. I did wonder at times how much they had asked questions to understand more of the context but in most cases the situation seemed quite clear, and they had raised the questions and felt the need to leave – showing a failure in leadership in their organisations.

During an ISA84 (161511) certification course, a fellow student asked me what I thought of his situation, where a safety interlock went off every week and was often bypassed. We talked about the situation in some detail and about the safety culture in which he was working. Based on some knowledge of the company’s safety record, and some people in the organisation’s process safety groups I knew that he was likely in an impossible situation. We talked about whether he had questioned it – he had! His leadership clearly knew about the safety instrumented system (SIS) requirement and was ignoring it for production gains. He had also raised it with the process safety group, which said that it was aware but couldn’t get anything changed, and was ignored. So, what was my advice? Find another job and write a letter to the director of that part of the business stating the reasons for leaving. There was a significant incident later at the place where he had worked.

But in this story, the challenge individuals face is apparent: it is extremely difficult for one person to change a company culture, and without ethical leadership, an ethical organisation cannot be achieved.

This puts significant responsibility on leaders to engender the right culture. I have always been struck by a saying of a previous mentor: “you get what you accept”. It’s easy to say the right things, but what matters, and what people see, are your actions. As leaders, we must lead by example, rewarding and praising the right culture and behaviours whilst calling out, redirecting and, if needed, disciplining the wrong behaviours.

As leaders we have a responsibility to think about ethics in all that we do; we can write the policies, we decide the budgets and decide what projects are going to be supported. We decide what prioritisation methods are used for maintenance, projects, and engineering time. We also set the metrics and reward systems - we get what we measure and pay attention to. We also very crucially decide what to listen to and follow up on. I can think of several occasions where someone was trying to tell me about an issue that I didn’t really understand and moved on to the myriad of other things I had on my plate, only coming back later, and realising that I could have acted faster. We saw in the Challenger disaster that the behaviour of a leader can make an engineer back down when it’s important for them to not back down. We need to ask the right questions and create the environment that the person can bring forward their concerns. The engineer also needs to learn good communication to communicate succinctly and well to managers who may not understand the issues being brought.

I was struck – moving back to the UK from 16 years in the US – to see plain English used in government documents and how clarity of communication can make a difference in understanding. Couple this with the benefits of explaining why decisions are taken or why polices are in place helps employees understand the context and helps them buy in or have the clarity to challenge and discuss. We need to be open to discussion and to ensure we put our decisions and organisational policies into context. We know that people are much more motivated when they can see the value and reason for their work, and hopefully if the organisation and the leadership is ethical, the employees can see that played out. The challenge for the leader is that must be consistent across every decision and action. It means we have to challenge ourselves to reflect, learn and improve.

As leaders we have a responsibility to think about ethics in all we do; we can write the policies, we decide the budgets and decide what projects are going to be supported

Interorganisational ethics

At the top level we have interorganisational ethics. Very large organisations can change the course of governments, huge employment investment or disinvestment in a local area and shape the key factors that drive a large part of an area’s economy – tax incentives. Is it ethical to move production to an area where regulation means you can operate in a way that wouldn’t be possible due to environmental or safety legislation? These are all real situations that companies face regularly, and some have standards and policies to prevent such ethically-questionable situations. Companies are more likely to hit the headlines when they make ethically-questioned decisions, for example P&O Ferries’ March sacking of 800 shipping staff and replacing them with cheaper agency workers.

How do you impact an organisation? We have seen shareholders and customers recently make overnight changes due to the conflict in Ukraine. We have seen the growing climate emergency drive companies to make changes; so it is possible. We of course, also have whistle blowers, which can come with very significant personal loss for the individual.

Many engineers get involved in groups that are influencing legislation or standards that organisations need to follow – including IChemE and many of our members working as volunteers on these committees and in the National Engineering Policy Centre (NEPC). We can make a difference – even if at times it feels impossible – and the answer is in working together. Make a difference and join one of the IChemE special interest groups or NEPC.

Ethical questions

Coming back to where we started – some questions to think about. Is it ethical to treat people differently, for example maternity and paternity leave? Or policies on LGBTQ+, treatment and accommodation for people with disability including neurodiversity? In your own decisions, day to day, stop to think about the implications. What about the organisations that haven’t pulled out of Russia due to the Ukrainian conflict; are you willing to keep working for them? What about greenwashing?

The UK Government has launched levelling-up initiatives. Through Covid-19 we learnt about the huge disparity across our country in access to the internet and computers. As we do our roles, should we think about how the technology changes, is available to, or impacts vulnerable groups? Over the last few decades, levels of poverty have increased despite incredible technology improvements. How can we impact that as individual engineers, as leaders, and as companies and governments?

Being ethical in everything we do is hard when the situation is so complex; however in hindsight it’s often very clear what wasn’t ethical. Perhaps we can ask ourselves: if this got into the press, or we had to tell our mother or partner – what would they think? All of us need to take a moment to think about the implications of what we are doing and consider stepping back and asking some questions and doing something different. I was inspired by the recent IChemE Presidential Address by David Bogle, bringing ethics to the front and centre in our thinking. I encourage you to watch the recording8. It would be great to hear your views and have a debate driving towards change and action.

References

1. Marsh, JH, The Quebec Bridge Disaster; The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://bit.ly/3BOiDR3

2. RAE, Engineering Ethics: Maintaining Society’s Trust in the Engineering Profession, https://bit.ly/3BIM07j

3. Mastura, AW, Is an Unsustainability Environmentally Unethical? Ethics Orientation, Environmental Sustainability Engagement and Performance; Journal of Cleaner Production 294 (2021): 126240.

4. Bowen, SA, Expansion of Ethics as the Tenth Generic Principle of Public Relations Excellence: A Kantian Theory and Model for Managing Ethical Issues; Journal of Public Relations Research, https://doi.org/fv5x74

5. Kuhar MJ, The Art and Ethics of Being a Good Colleague, second edition, 2020, ISBN-13 : 978-1479359325

6. Boekhorst, JA, The Role of Authentic Leadership in Fostering Workplace Inclusion: A Social Information Processing Perspective; Human Resource Management, 2015, Vol54, No2

7. Mitonga-Monga, J et al, 2016, Workplace Ethics Culture and Work Engagement: The Mediating Effect of Ethical Leadership in a Developing World Context; Journal Of Psychology in Africa, https://doi.org/gj3vx3

8. Bogle, D, Chemical Engineering: An Ethical Profession, https://bit.ly/3zZVJor

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Aoife Campbell, recently graduated in chemical and process engineering at the University of Sheffield, for significant research and assistance in preparing this article.

This article is part of a series on engineering ethics. For more articles, visit the series hub at: https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/tags/Ethics-and-the-Chemical-Engineer

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.