Brexit: The Impact on Energy and Climate Change

SINCE Brexit negotiations have entered full force, concerns are growing about the future of the UK’s climate change policy, a lot of which is underpinned by EU regulations.

These concerns are exacerbated by the UK government’s disintegration of the Department of Energy and Climate Change. The creation of the department was met with much fanfare in 2008: here was a department solely named to tackle climate change. Now that the government has abolished the department – even if the work does continue as part of another – the decision raises questions about how important climate change is to the current regime.

On top of this, we now have a minority government which makes its Brexit negotiating position weaker if an aspect requires approval by parliament. Minority governments have also proved historically less stable, meaning the long-term vision of leadership is vulnerable.

With all this at play, many are eager to know what the government will propose on energy and climate change in relation to the Brexit negotiations. This article discusses the main areas I expect will be impacted.

2008 Climate Change Act and our carbon budgets

The main legislation committing the UK to climate change action is the Climate Change Act (CCA) which commits the country to an 80% reduction in carbon emissions (from 1990 levels) by 2050. This is implemented via the carbon budgets, carbon emission reduction targets to be delivered in 5-year periods. The UK is currently reaching the end of the second carbon budget and is set to deliver its targets for the second and third budget, which would amount to a 37% carbon emissions reduction from 1990 levels by 2022. The fourth and fifth carbon budgets push these targets further to a 51% reduction by 2025 and a 57% reduction by 2030. The targets for the fourth and fifth budgets however, do not currently have the supporting mechanisms and legislation in place for the UK to be able to reach them.

Before the referendum, some environmentalists warned that the CCA might be unpicked if Britain voted to leave the EU. Although the Act is unilateral and set to remain in place, it is now being subjected to a major test: the UK’s plans to leave the EU, which governs a substantial proportion of UK emissions reduction policies. These commitments are not directly enforced by EU bodies, but many of the overarching frameworks and mechanisms of the UK strategy have relied on a coordinated EU strategy. My concern here is that current regulation doesn’t indicate how the UK would meet the targets post 2022, leaving the door open for politicians and industrial groups to possibly tamper with these targets with the aim of increasing economic output.

EU emissions trading system

The EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) is a cornerstone of the EU's policy to combat climate change and it is a key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively. It is also the world's first major carbon market and remains the biggest one.

The system works by putting a limit on overall emissions from covered installations, which is reduced each year. Within this limit, companies can buy and sell emission allowances as needed. This ‘cap-and-trade’ approach gives companies the flexibility they need to cut their emissions in the most cost-effective way.

The EU ETS covers approximately 10,000 power stations and manufacturing plants in the 28 EU Member States as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, and includes aviation activities in these countries. In total, around 45% of total EU greenhouse gas emissions are regulated by the EU ETS.

With the drop in sterling, we have seen the FTSE market increase in value as UK industries have become attractive to international investment. The low sterling creates the grounds for a stronger export economy. A typical economic strategy for the government would be to encourage manufacturing and ramp up industrial production. However this action would typically come with higher energy use and hence higher carbon emissions.

As the UK leaves the European Economic Area (EEA), the country would lose access to the EU ETS for our industries to trade for carbon. In this scenario, without the ETS to which the country can offset carbon emissions to, it is a challenge to increase industrial output and simultaneously meet carbon commitments.

Energy sources and production

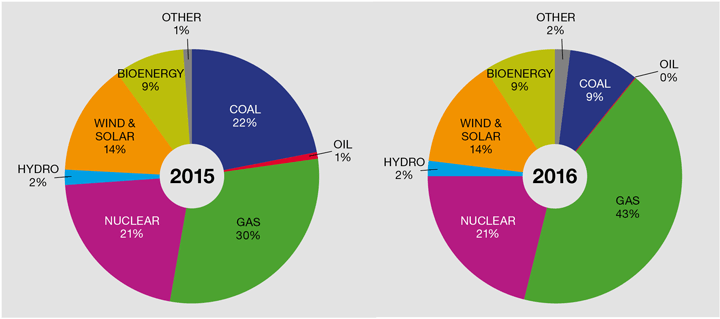

The UK’s main success in decarbonisation has been in electricity production. This sector has been changing in three major ways: coal, renewables, and gas.

The share of electricity production from coal has collapsed in a matter of a few years. This market change was spurred by legislation requiring all coal plants to be closed by 2025.

This has been compounded by high levels of investment into renewables since 2007. Where they used to provide close to 0% of UK electricity generation, they now provide near to 30%.

As a result, gas generation has grown massively. The reduced output from coal has required increased capacity from gas. This in itself is positive for the environment as gas burns cleaner than coal (driving higher air quality), but also more efficiently, reducing our carbon emissions.

Electricity generation from gas has also been on the increase due to the rise of renewables. As renewables produce power intermittently, gas power plants provide back-up to balance the grid, as they can be powered up or down swiftly, hence generating peak power. In short, they can be switched on quickly when the country needs more power as national grid tracks increased power demands, or as generation falls off from intermittent renewables.

The UK’s increased reliance on gas and renewables has led to the various interconnectors and energy trading with the EU coming under increased scrutiny .

i. Gas trading

Gas consumption for the UK in 2016 was 896,526 GWh. It is crucial for the country's heating, industrial processes and electricity production. In 2016, electricity production consumed 297,643 GWh of gas, equivalent to 33% of our total gas consumption, which as explained above, is only set to grow.

The government has been reinforcing the North Sea gas industry which produced 463,307 GWh of gas in 2016. Yet it was still necessary to import 534,740 GWh of gas, of which 122,310 GWh was LNG. Currently, LNG imports come mainly from Qatar (83% of LNG imports in Q1 2017), and are starting to come from the US too. The remainder, corresponding to 412,430 GWh was imported via pipelines from Norway or the EU, accounting for 46% of our consumption. With the current instability in the Gulf, I expect the price of LNG from Qatar, and hence the global scene, only to increase.

The clearest marker of this dependency is our gas pipelines to the continent. Most of the gas comes from Norway, which is connected through two pipelines: Langeled (capacity 80m m3/d) and Vesterled (capacity 38m m3 /d). Pipelines across the Channel are the Balgzand Bacton Line (BBL) which connects to the Netherlands (capacity 45m m3 /d) and the Interconnector with Belgium (capacity 72m m3 /d).

Not only do we rely heavily on the quantity of gas supplied, but we must also guarantee its constant supply. With the long-term gas storage facility at Rough closing, the UK is less capable of buffering for sudden consumption increases. This was testified during the cold spell of winter 2017/18, where National Grid Gas requested industrial gas users to implement demand-side response, making more gas available for domestic use. With fewer buffering system in place, the country is more reliant on the steady flow of gas imports.

The UK’s reliance on the continent for gas is fundamental to the UK’s energy security. Norway, as a member of the EEA, trades with the UK under the rules of the EU. Extra tariffs on these pipelines could therefore hinder the UK’s strategy which relies on gas peak generators to balance intermittent renewables.

ii. Electricity interconnectors

The UK is connected to the EU electrical grid through four interconnectors, providing a total maximum capacity of 4 GW, which are:

- 2 GW to France (IFA)

- 1 GW to the Netherlands (BritNed)

- 500 MW to Northern Ireland (Moyle)

- 500 MW to the Republic of Ireland (East West)

A further seven interconnectors are in development or planning which would add another 8.7 GW of capability.

These interconnectors are crucial, as they are the physical link enabling the UK to trade power with other countries in real time. The UK mainly imports power from the continent, with net imported energy in 2016 at 17.55 TWh, equating to 5.20% of the total UK consumption.

This figure shows how the UK is dependent on trading with the EU for power. This electricity traded on the Internal Energy Market (or IEM) is a crucial part of the EU development. Moreover, with renewables becoming a much larger share of the generation mix, both in the UK and in the EU, these trading points become crucial to maximise energy efficiency. As the UK does not yet have significant energy storage systems in place, there is a need to be able to sell electricity to the continent when, for example, the wind blows offshore from Scotland, and the sun is blocked in Spain. This is all part of the EU project to create a Supergrid.

Brexit could mean that the UK leaves the Supergrid project, within which the UK would be able to coordinate electricity generation and trade centrally across the European continent, leveraging the strengths of different renewable powers across various regions.

Brexit may cause extra tariffs to develop on these interconnectors. However, I would expect these to be unlikely scenarios from an EU perspective as the UK is a net consumer of electricity from the continent, and with many interconnectors in construction, adding tariffs to these would sabotage the commerciality of these investments.

The same issue applies for Northern Ireland (NI). The energy grid of the island of Ireland is one of the most integrated in the EU, but with NI a part of the UK, this grid integration could be required to be separated by force. We do also see interconnectors from Britain go to Ireland, which may suffer the same tariff issues as across the channel.

Euratom

Another effect of Brexit, which has hit the media, is leaving Euratom. Although the agency is technically independent of the EU, it does rely for its functioning on the European Court of Justice (or ECJ), commission and council of ministers, which has prompted the UK government to initiate moves away from the organisation. Its core focus is to promote nuclear research cooperation, establish uniform safety standards, ensure regular supply of ores and nuclear fuels, ensure nuclear materials are not diverted for other purposes, and ensure free movement of capital for investment in nuclear energy and specialists in the sector.

From the perspective of energy production, leaving Euratom may affect the UK’s supply of fissile materials for nuclear power plants. This may result in higher tariffs on the materials and/or delay their delivery. Barriers to investment and movement of personnel may also hinder research and the development of new nuclear power plants.

In particular for Euratom, but also significantly for the broader UK energy market, Brexit may lead to a disruption to research funding. Indeed, across the continent, the EU has been the funding source for "blue skies" research funding. Without the EU, we could see less funding towards these long-term research goals.

Continued cooperation in this regard can however be expected. Indeed, Euratom has cooperation agreements with eight external countries: US, Japan, Canada, Australia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and South Africa. The UK government also reached out on 13 July with its Nuclear Materials and Safeguards Issues position paper. This document assured that the UK would voluntarily take responsibility for meeting its safeguard obligations as agreed with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Furthermore, speaking on BBC Radio 4’s World at One on 14 July, Rachel Reeves, the Energy and Industrial Strategy committee chair announced the launch of an inquiry into Britain’s future Euratom membership. This measure is currently under debate between the two houses.

Conclusion

Reviewing the facts discussed above, I can paint a likely outcome for the picture of UK energy in 2020.

With both sides at stake to lose from tariffs, along with interconnectors still in construction, one would expect the UK energy markets to the EU for gas and electricity to remain mostly unchanged. With the carbon budgets set into UK law until 2030, Brexit shouldn’t directly affect our commitments to climate change. However, as the mechanisms to deliver these budgets have not been mapped beyond 2022, this does leave leeway for the UK intentions to shift from the law if major government and economic changes occur internally. The potential loss of the ETS would result in one fewer tool to meet these targets. As the case for Euratom shows, the biggest impact on the Energy sector is that leaving the EU will result in less coordination in research, financial barriers to investment and restricted access to skilled labour, which will impede our longer-term projects.

Whichever way the negotiations are resolved, the overall energy picture for the UK isn't set to change in the immediate future. However, acting as an independent agent and with the likely restricted access to EU investment and skills, the long-term energy picture beyond 2022 and 2030 for the UK is more unstable, and I’m concerned it will be less capable of responding to the needs of oncoming climate change.

Sources

2008 climate change act and carbon budgets

- https://bit.ly/2wq7l5p

- https://bit.ly/1V2UBq7

- https://ind.pn/2dKz4CU

- https://bit.ly/2I7OVb5

- https://bit.ly/2rv7GPv

- https://bit.ly/2KMHPul

- https://bit.ly/2des0KI

- https://bit.ly/2I6FNUd

EU Emissions trading system

Our energy sources

Gas trading

Electricity interconnectors

Euratom

Future energy leaders

Future Energy Leaders forms part of the IChemE Energy Centre, consisting of early-career professionals in the energy sector who demonstrate potential to be future leaders in the energy sector. Volunteer members provide support to deliver the Energy Centre’s policy statements, research and reports, and lead engagement activities around its priority areas. More information about Future Energy Leaders.

Recent Editions

Catch up on the latest news, views and jobs from The Chemical Engineer. Below are the four latest issues. View a wider selection of the archive from within the Magazine section of this site.